By Tracy G. Cassels

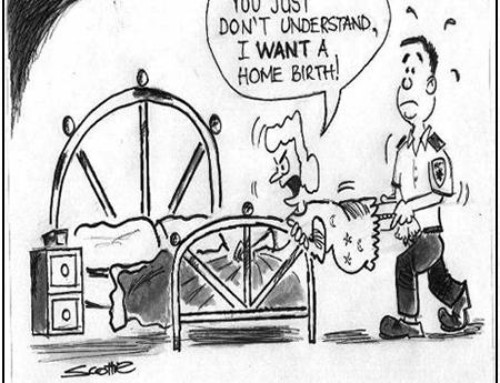

It has recently come to my attention that the state of Connecticut is in the process of making homebirth even harder for families to attempt. Already midwifery has been deemed the unlawful practice of medicine by the Department of Health’s Medical Examining Board. This less than a year after New York City went through a battle to ensure midwives were allowed to practice, thus allowing homebirth to continue. (I specify the bureaucrats because there are many doctors who would love to be able to perform deliveries drug-free and at a woman’s home, but they aren’t the ones who get to make all the decisions.) And while I have plenty of issues with modern-day medicine as it pertains to birth generally, I will be the first to acknowledge that it has saved many lives and has an incredibly vital role in childbearing. That role, however, is not to take over all pregnancies (low-risk or otherwise) and certainly not to feed fear and false information to women making them afraid of childbirth instead of welcoming the process. Sadly, that seems to be the path set out by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

What are the problems with homebirth according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists? The primary argument for years is that it’s somehow unsafe and that there hasn’t been enough research on it. It’s unclear to me how their opinion matters much to women when you study the history of obstetrics and gynecology and the suffering they caused millions of women and children over the years whilst messing with birth and the birthing process, but so be it. They say homebirth is unsafe and ignore the evidence that suggests otherwise. It would be great if they could take their collective heads out of the sand for a brief moment to actually read the literature on the topic because they might be rather surprised at what they find… namely that every well-done study that has examined the matter has found homebirth to be as safe or SAFER than a hospital birth for low-risk pregnanciese.g., With respect to interventions and morbidities (e.g., infections, lacerations), the advantage was for homebirth in almost all categories. Rates of cord prolapsed, large size for gestational age, and the need for newborn ventilation were equal amongst the two groups and rates of postdates (>= 42 weeks gestation) were higher for homebirths due to the fact that a planned hospital delivery in almost every Western nation would induce the mother prior to 42 weeks, but midwives will generally allow you to go to week 42 or 43 before inducing. Where the authors find support for the lack of safety of homebirth is in the mortality rates. Across all studies, neonatal, but not perinatal, death was found to be twice as high in the planned homebirth group. That finding alone should make this a done deal, eh? Not exactly. There are two glaring problems with this finding. First, it should be made clear that “neonatal” death refers to deaths in the first 28 days of life while “perinatal” death is death in the first 7 days; therefore, this increase in mortality seems to be happening 7 to 28 days AFTER birth (remember there were no differences in perinatal death rate). Generally, doctors consider perinatal death to be that related to birthing outcomes, and neonatal death due to other circumstances. So it begs the question why Wax and colleagues would even examine neonatal death, but again, we are left to say “so be it” and move on. We won’t ignore this difference though, as there could be for several reasons that are worth exploring. One, some studies only examined neonatal death rate, not perinatal, thus confounding the two outcomes, but that’s not the case for all studies, and the failure of a study to report perinatal rates would raise flags as to the value of the study when claiming to examine birth outcomes. Two, an infant who has problems during birth is able to hold on for over a week, but sadly dies after that 7-day period. It is possible, as medicine allows us to keep babies alive despite massive trauma during the birthing process or after, and not all women want that. Women who choose to deliver at home (because remember the biggest confound here is that women self-select into which group they want – planned homebirth versus planned hospital birth) may be more accepting of things going wrong and don’t want medical intervention, even in dire circumstances. Anecdotally, I had a conversation with a woman who lost her 4th child during a home birth (she safely delivered her other three at home too) and was told that there was a slim possibility that they may have “saved” the child in the hospital, but that that child would have lived with severe medical and mental problems for the remainder of his life. In her mind, the outcome, though awful and the worst thing she’s ever dealt with, spoke to her view that this child just wasn’t meant to be for this world. This same woman hoped to be able to deliver her 5th pregnancy (if she were able to get pregnant again) at home as well. In the same vein, some individuals simply do not like medical interventions in general and that may be part of the reason for selecting a homebirth. This could mean that an infant who has problems after birth may be less likely to receive medical attention if his or her parent doesn’t think highly of the medical community. Again, anecdotally, I know a woman whose daughter was born with a slight hole in her heart (homebirth) and although she was basically forced to bring her daughter in for one examination that first week after birth, she never bothered to bring her infant in for any follow-ups because of her disdain for doctors. Her daughter was fine in the end but had something gone wrong, it would have had absolutely nothing to do with the home birth per se. As strange as it may sound to some, there are people who think that it’s not just a matter of being alive, but being healthy and alive, and thus the extreme measures that are taken in hospitals is not for them. Whether that’s right or wrong is an entirely different debate, but it raises the issue that neonatal death, especially when there are no differences in perinatal death rates, may not be a factor relating to home birth, but rather both home birth and neonatal death are effects of a different cause. *Death rate as measured by deaths per 1,000 live births; **sample size in brackets Now, depending on the type of meta-analysis used (raw numbers instead of effect sizes), one could weight the numbers by the sample size, giving a hospital death rate of 4.08 and a home death rate of 5.41, seemingly significantly higher despite the fact that there are no differences in the individual studies. Why did this happen? Because the base rates for Sweden and the USA are different and there are unequal sample sizes in the studies, the low death rate for Sweden has disproportionally lowered the hospital death rate, leading to a larger difference when the studies were combined. Below are the sample sizes and real baseline rates[5] for the studies included in the neonatal death rate analysis: If you’ve been able to follow what I’ve been saying, you’ll be able to quickly see that the Swedish study is disproportionately lowering the infant death rate for the hospital group. And this is not because hospitals are safer in Sweden as there were no statistically significant differences in the individual study[6] (despite what the authors suggest in their discussion). Given the overall neonatal mortality rate differences by country, amalgamating the data is simply a bone-headed thing to do. So the study itself has glaring issues. Others have also pointed out that the data comes from a 30-year period which is also pretty ridiculously stupid given the changes in, well, everything over the last 30 years. Yet this is the best the medical community can come up with to try and take away a family’s right to have a home delivery. But there’s something else worth looking at too. There is one section in the report which I think should be the focus of the homebirth argument and yet is being ignored by the medical community: once studies were removed whereby the birth was attended by a non-certified individual, the cohort effects for neonatal death ceased to be significant. That means that once you removed studies which were not attended by a trained individual (usually a midwife), the neonatal death rates were comparable across the two groups. THIS should be the topic for discussion—namely, how do we ensure that all women have the option of finding a trained professional to help them deliver their baby either at the hospital OR at home? Solving this problem is nearly impossible when hospitals won’t allow transfers for women who encounter complications at home (see New York City’s case last year[7],[8])—by putting up these roadblocks to safe home deliveries, they put women at a greater risk of having life-threatening complications. The actions of the hospitals and administrators pretty much makes having a home birth a riskier decision in the USA, but even though that’s the case, when a woman has a certified midwife with hospital rights for transfer, a home birth remains as safe as hospital births. The REAL issue then becomes the treatment of midwives (a larger topic for another day). Briefly, because the USA does not consider midwifery a viable and real option for pregnant women and midwives in the USA have not worked to form their own college with their own set of standards of education and care, it is can be a riskier decision because of a variety of factors (e.g., not enough training, no backup). Now, that said, the vast majority are probably trained better than we could imagine (and many have better training than doctors with respect to “normal” births), but without that network of support, they become easy targets for the medical community and can be ruined by a few bad apples. Western countries that have integrated midwifery into their birthing model (e.g., parts of Europe, Canada) have higher homebirth rates and lower infant death rates than the USA. Even Dr. Wax and colleagues acknowledge in their study that the countries whereby midwifery has been integrated into the medical system show absolutely no deleterious effects of homebirth; in fact, those studies show home birth advantages. The fact of the matter is that homebirth can be unbelievably safe, and if you look at the data1,2,3, it can regularly be safer than delivering in a hospital. However, for optimal safety, you want to ensure that you have a trained professional there with you. As long as doctors won’t (or aren’t allowed to) do home births and midwives are pushed the side, no one will win, certainly not the laboring woman and her child. The answer is not to force women to hospitals, as has been the case in the USA, but rather to ensure that every woman who chooses to give birth at home is given the help she needs to make it the safe and wonderful experience it can be. [1] Wiegars TA, Keirse MJNC, van der Zee J, & Berghs GAH. Outcome of planned home and planned hospital births in low risk pregnancies: prospective study in midwifery practices in the Netherlands. British Medical Journal 1996; 313: 1309. [2] Janssen PA, Lee SK, Ryan EM, et al. Outcomes of planned home births versus planned hospital births after regulation of midwifery in British Columbia. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2002; 166: 315-23. [3] Janssen PA, Saxell L, Page LA, Klein MC, Liston RM, & Lee SK. Outcomes of planned home birth with registered midwife versus planned hospital birth with midwife or physician. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2009; 181: 377-383. [4] Wax JR, Lucas FL, Lamont M, Pinette MG, Cartin A, & Blackstone J. Maternal and newborn outcomes in planned homebirth vs planned hospital births: a metaanalysis. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2010; 203: 243.e1-243.e8. [5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_infant_mortality_rate [6] Lindgren HE, Radestad IJ, Christensson K,& Hildengsson IM. Outcomes of planned home births compared to hospital births in Sweden between1992 and 2004: a population-based register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010; 87: 751-9. [7] http://www.opposingviews.com/i/there-are-no-legal-midwives-left-in-new-york-city [8] http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/18/nyregion/18midwives.html

At the moment there is one article making the rounds as evidence of the dangers of homebirth. Dr. Joseph Wax and colleagues performed a meta-analysis on 12 different studies examining the safety of planned homebirths versus planned hospital births[4]. A meta-analysis is kind of like merging the data for all the studies into one big study to analyze the data with a larger dataset. It’s incredibly powerful and generally considered much better than any individual study because it allows you to understand a pattern of results, especially when the datasets for individual studies are small. But the data included in this meta-analysis ranged from top-notch, high-quality, large sample size studies to poor quality, small sample size studies. These two should never be mixed. Low quality studies should never be included in a meta-analysis because of their poor quality. However, that taken into account, let’s examine what Dr. Wax and colleagues found…

Second, and probably more importantly, even if we accept Wax et al.’s view that the neonatal rate is related to birth location, there’s the large methodological problem with this meta-analysis (on top of the problem of including different quality studies). For this particular analysis, only six studies were included and they were from the following locations: California (USA), Australia, Sweden, British Columbia (Canada), Washington State (USA), and Switzerland. Now the way a meta-analysis works is that you merge the cases from all of these studies to create one big study and analyze that. This means that the sample size of each study serves as its weight towards the meta-analysis; so studies with larger samples are weighed more heavily than those with small samples. This works when the baseline rates which you examine are the same or if each study has the same sample size for each of their cohorts, but neither of those is true in this case. Let me explain. Because we’re looking at neonatal death rates, we have to consider that different countries have different neonatal death rates in general, and that’s due (in part) to differences in the health care systems and lifestyles of each country. So by blending these studies together, you run the risk of messing things up because there are different baseline rates. If, however, the sample sizes of the two groups (home and hospital) were the same in each study, the national differences would wash out. For example, say we looked at two studies from two countries and this was the data (note that this is made up data, but approximate to real baseline rates)

Home*

Hospital*

USA

6.5 (800)

6.0 (1,000)

Sweden

2.5 (300)

2.8 (1,500)

Home

Hospital

Infant Mortality Rate

California (USA)

454

67

6.26

Western Australia

976

2928

4.75

Switzerland

489

385

4.18

Sweden

897

11,341

2.75

British Columbia (Canada)

862

1314

5.04

Washington (USA)

6133

10,593

6.26

Well said. Whenever you read research and statistics, always, ALWAYS follow the trail. Who wrote it, what is their motive and where does their allegiance lie.

Also, the Washington State study did NOT distinguish between planned and unplanned out-of-hospital birth. And, of course, the oh-so-conveniently did not include the large, recent, North American studies that have concluded that homebirth is at least as safe as hospital birth. IIRC, even the Institute of Medicine has said that the Wax study is junk science.

Home births probably could be safer as they said if Doctors were allowed to be present for home births, but there is one large reason that this cannot and will not happen and we can thank our own society of law suits and suing for everything for that. If something ever goes wrong people sue first and never think that sometimes things could go wrong anyways. These are the type of people that have ruined the way medicine could be and the way that doctors practice.

Having GPs would be great, but midwives in countries where home birth is part of the system are HIGHLY trained. But yes, I imagine litigation has a huge effect on the issue 🙁