One of the things I hear parents lamenting more than anything as their sweet bundle of joy turns into a talking and walking toddler is that suddenly they have yet another person in the house who doesn’t listen to them. Parents often expect a toddler to not just listen to them, but obey them, and so of course it’s infuriating when they don’t, especially if you feel that you are being a gentle, respectful parent. It can start to feel a little personal. The problem is that it’s just not realistic and misses some of the more crucial points when we talk about toddler behaviours and expectations. Now, I’m not saying we should all expect our children to never listen to us or that we shouldn’t aim to get them to work with us as often as possible, but before we talk about the ways in which we may sabotage that process, we have to talk about the reality we can expect from our younger children.

The Toddler Brain

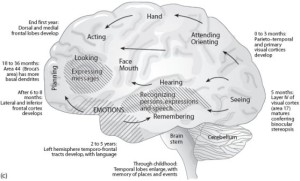

By the end of the first three years the brain has undergone rapid and extensive development[1], but there is still a long, long way to go and one of the areas that still requires extensive development at this age is the prefrontal cortex which actually isn’t finished developing until we’re into our 20s[2][3]. At birth and continuing for the first three years, there is immense synaptic growth – so much that we couldn’t function with that many connections for our entire lives. This means the next part of neural development is what we call “pruning”, where synaptic connections that aren’t strong enough end up dying or being pruned away. This starts around 12 months of age but continues into our 20s[3]. Pruning is the process by which our brains map the paths our brain will make in response to our environment and situations based on the strength of these connections that come from our experiences. And again, it seems to come later in the prefrontal cortex.

Why does the prefrontal cortex matter? It’s is to help us regulate our behaviours, reduce impulsivity, and all that fun stuff us parents like to think of as “listening”. Now, this doesn’t mean toddlers have no inhibitory control, but that their control is very limited and not nearly as advanced as that of a grown adult. It increases as your child ages, but we must always be aware of their limited development when looking at their behaviour. Some of the functions that the prefrontal cortex is involved with include[4]:

- Planning

- Decision making

- Emotional responses to situations (i.e., emotion regulation)

- Attention and concentration

- Working memory

If you think of your toddler and how they sometimes respond when you ask them to do something or stop something, can you see why they may be having a pretty hard time?

What Can A Parent Do?

Even though there are neurological reasons a child may not immediately respond to you or do what you ask, know that many children are capable of listening and responding if we work with them where they are at. There are also many things parents do that reduce the likelihood that a child will listen to them and some things they should consider doing if they want their child to listen. Remember though: We’re talking about getting your child to listen, but that doesn’t necessarily mean obey so make sure you are also willing to discuss the situation with your child once you know they are listening.

(As a quick aside, if your child really seems as if s/he cannot follow what you are saying or doesn’t ever look at you when you talk, you may want to consider visiting your doctor to look for other possible causes.)

The following steps are ones you can take to help meet your toddler where they are at to help alleviate your own stress over the issue of “listening”:

Look At Your Child. I realize in our society we are used to being able to talk to people without looking at them and they know we are trying to communicate with them, but early on, children don’t have this sense. Eye gaze is one of the biggest cues children use to understand both what people are talking about and who they are talking to[5] and it’s essential we use it with them. This is particularly essential if we are talking about something important for eye contact tells us that our child is focused on us and not something else (and equally important tells them that we are focused on them and nothing else).

Redirection Over Commands. Often I hear myself and other parents just use “Stop!” when we don’t like what our children are doing, but this is one of the things that’s difficult for a brain that doesn’t have a developed prefrontal cortex. One way researchers assess the development of inhibitory control in preschoolers is using a card switching task. This research finds there is a clear developmental trajectory in which young children can inhibit or switch behaviours when it’s simple or easy, but the more complex the behaviour or the task, the more difficult it is[6].

This is why just saying stop won’t necessarily help when a child is engaged in something because that will always be complex and enjoyable to them (and of course being involved means they also are less likely to even hear what you’re asking, especially if you never got that eye contact). If you need a behaviour to stop, kids will require your help and one of the best ways to help is to explicitly redirect the action. For example, imagine a child is painting on the walls. He is likely absorbed in the task and just hearing “Stop that!” won’t elicit stopping because it’s like he’s on a loop where he just has to and wants to keep going. Instead, going over and acknowledging the work (“Wow – I can see you like to paint!”) then redirecting somewhere else (“Why don’t you paint on this easel instead as we’re not allowed to paint on the walls”) will often do the trick. Not only does it change the behaviour, but it teaches another appropriate behaviour that the child can go to the next time there’s a desire to be creative.

Save Your “No”s and “Stop”s. If you spent a day counting the amount of time you said “no” or “stop” you might be surprised. Parents find themselves saying it in response to almost everything, and especially in response to little things that really aren’t all that important. The problem is that if you use these words too much, they lose their power. (Now it may not be the specific words you use, but the tone of voice as well as that can convey the message of frustration or annoyance and you also want to limit this.) Figuring out the words or tone you want to use when you really need your kids to listen is important; then focus on only using it when you really have to. After all, if our children as so used to hearing these words multiple times a day, is it a wonder they stop listening and just tune us out?

Don’t Yell. I kind of lied above. There is one time at which children will stop when you say “Stop!” and that’s when they feel fear and there are three ways in which this can happen: (1) The child hears the fear in her parent’s voice; (2) The child hears the words from the parent and knows their seriousness because they aren’t used often; or (3) The child hears the anger in the parent’s voice and feels fear from that. Case 1 is a legitimate use of fear and is what we are biologically primed for. Case 2 is what I spoke about above with respect to saving your words for when absolutely necessary. Case 3 is the case of yelling or punishment. You might think that it’s just as good as 1 or 2 if it gets the same short-term results, but you would be wrong.

When children respond out of fear, they don’t learn how to manage their own emotions or behaviour[7], which should be what we are aiming for in the long-run. As such, yelling isn’t a good socialization tool and is often only used when we feel we’ve lost control. Although it may instill some short-term changes, as your children adapt to your yelling, it becomes like the words “no” or “stop” and you may end up escalating. As Dr. Elizabeth Gershoff said with respect to physical punishment, “[It] doesn’t work to get kids to comply, so parents think they have to keep escalating it. That is why it’s so dangerous.”

Listen to Your Kids. If there is only one thing you take from this, it’s that you need to listen to your children too. I’m not talking just about in the moment when you’re trying to get them to stop something or work with you (because clearly if they are trying to explain why they are doing something and why it is important to them, you ought to listen and take it into consideration), but more generally parents don’t always listen. Research shows that parents who listen to their children and follow their lead when it’s possible have children who are more likely to not only listen to their parents, but follow along when the parents make a request[8]. In the larger scheme of things, if you create an environment where your child feels heard and respected, they are likely to reciprocate that respect and when you need cooperation, they are going to be more likely to listen to what you have to say and talk it out with you.

***

Listening is a complex behaviour that isn’t just about what happens in the moment. It requires a larger look at how we’re behaving in the larger scheme of things and understanding the limitations that our younger children have. When we know these limitations, we can alter our behaviour to make sure we maximize our interactions with them and reduce our own frustrations. For more on discipline, you can check out my course Sharing Control: A Course on Discipline Across the Ages.

This is very helpful thanks. Lots here for me to work on with my 3 and 4 year old sons who I’m struggling to relate to. Something I don’t understand though – when I say “let’s go out, come and get your shoes on” they don’t understand, but when I even whisper “chocolate” they definitely understand?!!!

I’m sorry, I’m now required to quote (well, paraphrase, its been awhile since I heard the skit) Bill Cosby at you:

“I don’t understand it when I hear parents complaining about their toddler not listening or obeying. ‘I tell them to come here and they just won’t listen!’ Excuse me? You say ‘come here’ and when they ignore you, you go over to the child, pick them up and say ‘that’s ‘yes!”.”

In general you know we agree on most child-rearing concepts, but echo chambers aren’t really much for intellectual development. 😉 When the child is so young they are physically incapable of obeying or listening, it’s the parents job to make sure they do so by our physical interaction with them. That ‘pruning’ process is guided less by age and more by what the brain is doing. So if we never ask it to do certain tasks, then, yes, it takes 20 plus years to finish, but other pathways are solidly in place much sooner-because those that are actively used get priority. So if we make development of self-control and decision-making the priorities in our daily lives, it’s just plain old cultural-bias bunk to say it takes until the 20’s for those pathways to get properly set. Throughout history things we in American today would think of as ‘impossible’ for a child to do were perfectly common in another time/place. It all has to do with what you demand of people, most people, children included, will rise to the occasion when set a high bar. Of course there is a curve, but if *most* 3/5/8/15 year olds were once capable of it, or are capable of it in a different society, then we aren’t talking about limitations of the human brain, we’re talking about limitations of how a specific human is being raised. We shouldn’t confuse the those two. Doctors in 18th century Europe/America *knew* women developed a certain way and had certain inherent internal problems. It was in the medical textbooks and standard knowledge of the day. These issues were inherent to the female of the species. It wasn’t until corseting fell out of style they suddenly learned that those were not inherent problems, but rather was an issue with how all the women they were studying were being raised. We’ve spoken about how most development/cognition studies are done on white city people from the western world. Today they parrot nonsense about how a small child ‘can’t’ be expected to exhibit certain developmental behaviors only because they have forgotten that they are only (or at least primarily) looking at children who have never been asked to exhibit those behaviors. Are we to believe that the modern western child is actually incapable of exhibiting behavior not only once believed to be perfectly normal for the age but also still is believed to be perfectly normal for the age in other cultures today (including subcultures within the western world) or are we to believe that the situation they are being raised in is artificially retarding their abilities to develop in a normal manner? As for me and my house, I’ll expect my children to develop upon a normal curve. Which means when I call my 2 year old’s name, I expect her to pick her head up and see what I want-even if she is engrossed in an activity. And, by golly wouldn’t you know it, she’s developed perfectly normally and does so. The western world needs to reexamine how we are ‘corsetting’ our children that we expect so little of them that our scientists have actually come to consider it a benchmark.

I love our debates… yes, some is expectation, but as you know, Maddy does the same (although I’ve had times she has legitimately not heard she’s been so engrossed and I’m the same) yet I don’t physically force her to listen or “obey”. The issue – and I’ve seen you interact with your kids so I know the same holds for you – is that you (a) don’t use “no” unnecessarily meaning they learn to ignore it (which I think is probably one of the BIGGEST problems in our society in how we raise kids – we are constantly saying it whereas historically kids were left to their own devices more often), and (b) listen to your kids when they talk to you. I think the lack of expectations that you speak of stem from failure of most families in these two regards more than anything else. I DO expect my child to listen, but I understand some of the causes in our society of why other kids don’t and I don’t think it’s expectations – it’s the way we treat them and hover over every little thing.

As for actual brain development, whether it has changed with time, neurological imaging shows us the prefrontal cortex develops when it does (i.e., late) but it doesn’t mean it has NO function in the interim.

“neurological imaging shows” the brain of the person you are imaging. See above about corseting. Those images that are being used to determine the benchmarks are being taken from people culturally and artificially stunted. I’ve yet to see a study on development based around imaging studies on Congo tribesmen who are considered adults and of marriageable/family age at 14. Nor on African children who find it perfectly normal to care for hearth and home, cook, tend the fire, gather wood/food, and care for younger siblings at 6. When someone compares the ‘uncorsetted’ brain of a functional adult at 15 to the ‘average’ western 15 year old ‘child’ and finds that the adult has no more brain development in the prefrontal cortex than the child, *then* I’ll agree with you.. Until then, you’re still looking at the study on corseted women and saying that it’s natural and normal for a woman’s spine to bend and twist in adolescence and using that as a benchmark for what ‘humans’ can and cannot do. Science is only as good as the assumptions that go into designing and interpreting the study.

Very interesting point. Though I would ask what you thought of the other part of what I said – about how the problems are to do with not expectations but how we approach the topic of listening in Western society.

I’m still suffering from head-cold I.Q. drain and I swear I’ve read your initial reply a dozen times and I’m still not sure quite what you mean. As far as I can tell, you somewhat answered your own question by acknowledging I don’t hover and rarely say ‘no’. I think the reason we as a society have such low expectation for our children, why a 15 year old today is referred to as a child who can not possibly be expected to make good decisions or practice self control and why a 6 year old can’t be given a pocket knife and bb gun, is precisely because our society starts by hovering over toddlers like they are still infants and never gets over that stage, children are treated like toddlers, adolescents like children, and adults like adolescents. I’m not sure what listening, either good listening or bad listening, has to do with it. Certainly the over-abundance of ‘no’s’ do, but there are many very traditional societies where children almost never had meaningful conversation-and certainly not random conversation-with adults including their parents I’m not sure that listening to children could be really considered positive or negative from a physiological perspective. I’m also feeling very much, however, like I’m missing your point or we’re dancing around the same subject with some troublesome word choices, so I’m not sure I’m answering the right concept. Certainly the trouble isn’t with the children, but with how the adults are raising them.

Sorry – I’ve been gone all weekend. I think the “no” and listening to your kid go hand in hand. When you avoid too many no’s it’s because you (a) see that some things aren’t worth fighting over, but (b) acknowledge the child has a reason and if it won’t kill them, let ’em try it. I think in the end we’re more in agreement than not. I do, however, believe that people can function as they have without a fully-developed prefrontal cortex, but the expectations we put on young kids are a little ridiculous. I have met parents that expect toddlers to obey every command. It’s ridiculous.

This post that I read a while ago really opened my eyes to this issue. Western culture has so many, “no’s” for children. As far as traditional societies go there are a lot less no’s and the dangers are a lot more clear. It’s kind of like trying to learn something and having someone lay down a constant stream of advice. It makes it hard to concentrate, it’s stressful. Everyone needs space to learn. And I really don’t think that there is this huge prevalence of not having high enough expectations for children. I think that most people have really high expectations as far as self-regulation, listening, and obeying. Then there seems to be this general sense of really low expectations for children to Do things. As a culture we expect children to listen and rationalize what we are telling them to do, remember it day-to-day, and stop themselves from doing it. But as a culture we are impatient with them. We want them to do it Now, and if they don’t then we are going to do it for them. We have this fear that if we don’t teach them right-this-minute, that they’ll never learn. And at the playground I see people micromanaging children. We expect them to instantly obey us, but we don’t trust them to decide if they want to go down the slide or not? We don’t trust them to know if they like something they are eating or not? We don’t trust them to know if they are upset or not? It’s incredibly weird.

http://schoolingtheworld.org/a-thousand-rivers/