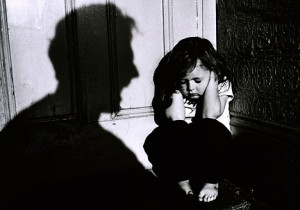

Child abuse by parents is a tricky topic to discuss for all parents, one we’d like to all avoid if possible, but one that should never be avoided because of its importance. Luckily, abuse is still something that occurs in the minority of cases, and even families with lots of risk factors for abuse won’t abuse or neglect their child. Evolutionarily speaking, we’re not supposed to – we’re supposed to feel an intense bond with our child that helps us to help protect them. Yet we still see children being physically abused, sexually abused, psychologically abused, and downright neglected. It is my belief that our systematic movement away from our evolutionary roots to parenting are contributing to this problem. What you’ll read herein is not meant to be a condemnation of any parent who utilizes some of these methods, but rather an examination of certain parenting characteristics that are rather new to society (evolutionarily speaking) that have been empirically associated (though not proven causal) with a heightened risk of child maltreatment. Sadly parent characteristics have often been overlooked in favour of societal characteristics (e.g, poverty) and yet as parents, we have the power to overcome certain external factors to help our children thrive, if only we could focus on what parents can do.

Child abuse by parents is a tricky topic to discuss for all parents, one we’d like to all avoid if possible, but one that should never be avoided because of its importance. Luckily, abuse is still something that occurs in the minority of cases, and even families with lots of risk factors for abuse won’t abuse or neglect their child. Evolutionarily speaking, we’re not supposed to – we’re supposed to feel an intense bond with our child that helps us to help protect them. Yet we still see children being physically abused, sexually abused, psychologically abused, and downright neglected. It is my belief that our systematic movement away from our evolutionary roots to parenting are contributing to this problem. What you’ll read herein is not meant to be a condemnation of any parent who utilizes some of these methods, but rather an examination of certain parenting characteristics that are rather new to society (evolutionarily speaking) that have been empirically associated (though not proven causal) with a heightened risk of child maltreatment. Sadly parent characteristics have often been overlooked in favour of societal characteristics (e.g, poverty) and yet as parents, we have the power to overcome certain external factors to help our children thrive, if only we could focus on what parents can do.

Isolationism

One of the biggest changes to the way in which we parent, and one I’ve discussed at length on this site, is the degree to which new mothers are isolated from the rest of society. Yes, there are some new moms groups that you can go to weekly or some parks, but by and large, most moms are on their own dealing with a newborn. And when you’re on your own, the level of stress you experience is drastically higher because you have fewer people to help you out both instrumentally and emotionally. And parenting stress is directly linked to risk of abuse What can we do? I’m sure most people’s first thoughts would be a program that brings people to a family home to help out or check members of the family to set them up with support. The problem is that much research on this has not found it to work with respect to reducing the chances of abuse or neglect[5][6]. One of the problems, as identified by the researchers involved in this, is that home visitors often failed to notice the risk factors during their visits and thus failed to refer to families to the appropriate community services[6]. This shouldn’t be too surprising given that these are people coming in for segments of time without a fuller understanding of the family as a functioning unit. Of course, if the study were to only involve offering instrumental support, like doing laundry or cooking a meal or holding the infant while mom gets a nap or sleep, benefits may be found, and one research program has found as much[7]. But unfortunately, governments rarely want to implement something so simple. They have to have assessments and referrals and everything else under the sun. This is why I believe it’s so important for communities to be formed again and work together to help each other out. Indeed, research has found that a built in support system for the family is a protective factor for children at-risk of being maltreated[8]. When you’re a part of a community, the people know you, know the risks, and can work to help the family out in ways government officials never could. Breastfeeding This one is bound to be contentious because anything about breastfeeding seems to be contentious. Let me remind everyone that this does not mean bottle-fed babies will be abused or neglected as we’re talking about risks. But here we do have research showing that bottle-fed babies have a higher risk (2.6 times) of being maltreated than breastfeeding babies, and this is controlling for other factors like income, education, and other socio-demographic variables[9]. Notably, when the socio-demographic variables are not controlled for, the risk is far greater at 4.8 times more likely to be abused, so there is clearly a link between these socio-demographic factors and whether or not one breastfeeds. However, the fact that the risk remains at 2.6 times when all these other factors are controlled for begs the question of what is going on? While the researchers of this particular study did not examine potential hypotheses, it seems logical to assume the effect is in part due to hormones produced during breastfeeding; specifically, oxytocin, which is known as the love hormone and is known to put people in a loving, caring, and nurturing mood. Not only does breastfeeding in and of itself produce oxytocin, but the skin-to-skin contact that is part of breastfeeding also promotes the release of oxytocin. What can we do? For starters, we can promote breastfeeding more than we currently do. As much as we see ads and doctors talking the talk, very few places walk the walk. As soon as someone talks about the benefits of breastfeeding, they are branded a breast-nazi or something equally asinine, and yet we need to make people aware of the various benefits. As for those who cannot breastfeed, we need to ensure we push for parents to do other activities that promote the release of oxytocin, such as lots of skin-to-skin contact (while feeding or not). Parental Warmth It may sound funny, but a lot of people don’t realize exactly what ‘parental warmth’ refers to. In research, parental warmth refers to the positive affect and affection a parent can demonstrate to their child; this is different from responsiveness to distress in which a parent reacts, however warmly, to their child when he or she is upset and sad[10]. While it may not be surprising to many, lower levels of parental warmth have been linked with a heightened risk of child abuse and neglect[11]. The problem, as I see it, is that we live in a society that we live in a society in which this type of affection is not as common as it should be. We have strollers that keep us at a distance from our kids. We have TV which far too many children are plopped in front of for far too long (I’m not talking about the hour a child may watch throughout the day, but the parents who use it as a babysitter). These things keep us from being affectionate with our kids. But in addition, we have unbelievably high expectations for our kids and in turn, when they reach them, we’re just relieved, and we worry insanely when they don’t. How can we offer the positive affect and affection when we’re too stressed out ourselves? When a child learns to walk nowadays, it’s met with relief, meaning the entire time prior to that, the parent was experiencing stress and that’s what children pick up on. And given that stress is a major risk factor for child maltreatment, I personally wonder if our expectations are harming our children even more. As important as the risk to child maltreatment, parental warmth has been implicated as a protective factor for children who have already been abused[12]. That is, for children who have already been abused by another person, the level of parental warmth displayed to that child helps prevent certain long-term effects such as depression and later self-esteem. Given its relationship to positive affect regulation in non-abused children[10], it makes sense that it could help protect children who have endured a particular trauma. What can we do? First and foremost, we need to remind parents how important this warmth can be for their children. But secondly, I do believe we need to get rid of these insane expectations we have for our children. There’s nothing wrong with wanting them to do well and helping them along the way, but if it becomes too much and you find yourself stressed about it all the time, you probably aren’t enjoying the time you are spending with your child and that puts them at risk. Not to mention stressing you out. Attachment While many of the individual components of Attachment or Evolutionary Parenting have not been examined, as a whole, the better the attachment relationship to your child, the less likely your child is to be maltreated[13]. Very specifically, one study found that insecure attachment was much more likely in families with sexual abuse than families without incidents of sexual abuse[14]. And while it would be no surprise to see attachment problems post-abuse, it has been suggested that attachment problems can precede abuse and be present in non-abusive relationships in abusive families (e.g., siblings of abused children also show attachment problems). The question becomes what aspects of attachment parenting are most likely to contribute to this risk. In an overview of the research on attachment status and abuse, it was found that the dominant aspect of parenting that qualified a securely attached versus insecurely attached relationship was sensitivity, or responsiveness to distress[15], though many would argue that the myriad components of attachment parenting contribute to this sensitivity. What can we do? Quite plainly and simply, we can promote practices that build attachment. But we also need to focus on ending the practice of encouraging practices that tell parents to ignore their children when they are truly distressed. Parents who routinely learn to ignore their instincts and their children most likely lose confidence in their parenting abilities. If you’re told over and over that what you instinctively feel is right, is wrong, then how can you trust yourself? And there is research that a lack of confidence in parenting abilities is a large risk-factor for child maltreatment[1]. What is often overlooked is that evolutionary parenting practices are instinctual for many of us because that is how we have evolved. Biologically we are supposed to keep our offspring close, breastfeed them, and respond to them to keep them alive and well. And these things build attachment – secure, healthy attachment. Conclusions This kind of research does not and will never be able to demonstrate a causal effect (after all, you can’t force people to perform attachment parenting practices if they aren’t willing), but it raises the possibility that attachment parenting, with the degree of closeness it entails, serves to reduce the incidences of child maltreatment. It is worth remembering that some earlier, hunter-gatherer/native/primitive societies were more peaceful than we probably imagine. Certainly far more peaceful than we are today (despite what Steven Pinker would have us believe, but then he didn’t examine all of human history). [1] Holden EW, Banez GA. Child abuse potential and parenting stress within maltreating families. Journal of Family Violence 1996; 11: 1-12. [2] Chan YC. Parenting stress and social support of mothers who physically abuse their children in Hong Kong. Child Abuse & Neglect 1994; 18: 261-269. [3] Murphy S, Orkow B, Nicola RM. Prenatal prediction of child abuse and neglect: a prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect 1985; 9: 225-235. [4] Leventhal JM, Garber RB, Brady CA. Identification during the postpartum period of infants who are at high risk of child maltreatment. Behavior Pediatrics 1989; 114: 481-487. [5] Siegel E, Bauman KE, Schaefer ES, Saunders MM, Ingram DD. Hospital and home support during infancy: impact on maternal attachment, child abuse and neglect, and health care utilization. Pediatrics 1980; 66: 183-190. [6] Duggan A, Fuddy L, Burrell L, Higman SM, McFarlane E, Windham A, Sia C. Randomized trial of a statewide home visiting program to prevent child abuse: impact in reducing parental risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect 2004; 28: 623-643. [7] Jackson AP, Brooks-Gunn J, Huang C, Glassman M. Single mothers in low-wage jobs: financial strain, parenting, and preschoolers’ outcomes. Child Development 2000; 71: 1409-1423. [8] Li F, Godinet MT, Arnsberger P. Protective factors among families with children at risk of maltreatment: follow up to early school years. Children and Youth Services Review 2011; 33: 139-148. [9] Strathern L, Mamun AA, Najman JM, O’Callaghan MJ. Does breastfeeding protect against substantiated child abuse and neglect? A 15-year cohort study. Pediatrics 2009; 123: 483-493. [10] Davidov M, Grusec JE. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development 2006; 77: 44-58. [11] Slack KS, Holl JL, McDaniel M, Yoo J, Bolger K. Understanding the risks of child neglect: An exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment 2004; 9: 395-408. [12] Weissmann T, Silvern L. Parenting and family stress as mediators of long-term effects of child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect 1994; 18: 439-453. [13] Rogosh FA, Cicchetti D, Shields A, Toth SL. Parenting dysfunction in child maltreatment. In Marc H. Bornstein (Ed.) Handbook of parenting, Vol 4: Applied and practical parenting (pp127-159). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. (1995). [14] Alexander PC. Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1992; 60: 185-195. [15] Morton N, Browne KD. Theory and observation of attachment and its relation to child maltreatment: a review. Child Abuse & Neglect 1998; 22: 1093-1104.

I know you’re simplifying things here, but you need to be careful about correlation not being the same as causation – you briefly mention this at the end as sort of an afterthought but for the whole post you strongly imply causality, especially since you suggest that by manipulating these variables we could decrease child abuse. To me, except for social isolation, these scream “personality” (or depression, or happiness about being a parent, etc.) – on average parents who commit child abuse quite likely aren’t all that warm and fuzzy in their interactions with their child (or with other people for that matter); probably aren’t very consistent or sensitive (decreasing attachment security); are less committed to make the effort of breastfeeding… So suggesting that by encouraging parents to be warm one could decrease child abuse is a bit like suggesting one can reduce depression by encouraging people to be less sad – that’s going after the symptom, not the cause.

Patricia – yes, correlation is not causation, but actually in therapy, a lot is faking it until you make it. Especially with depression 🙂 But the focus of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is kind of like what you described – just change your behaviour and the mental state follows. If someone is depressed, you have them go out more until the behaviour of going out elicits the happiness they need. Anxiety is treated via exposure. Basically, the therapy realizes that hormone changes happen because of behaviour, and with children, the closeness really does elicit oxytocin which in and of itself causes (yes, causes) happiness 🙂 So while I don’t know that making the changes would necessarily cause a reduction, in some cases it clearly might! (Especially the research on breastfeeding which truly controlled for a ton of factors.)

One thing with the breastfeeding that has always struck me: sleep deprovation. I think for reasons we all would find obvious singular instances or initial instances of child abuse (at least in the early years) often seem related to parents just ‘snapping’. Lack of sleep always has seemed like it probably plays a huge motivator in such instances. Not only do most breastfeeding moms get more sleep, but breastfeeding women are actually biologically better capable of dealing with limited sleep due to the hormone releases that go with breastfeeding.

I have to disagree with that last bit about us being more violent that primative cultures though. In some aspects you may be right, and certainly in reference to some societies. But a huge number of early civilizations practicied truly barbaric rituals, rites, cerimonies, celebrations, or just aspects to life. We have a greater chance to be destructive on a large scale, certainly, due to technology, but we also have eschewed many of the violent practices that were once taken for granted. There’s nothing new under the sun, and man has always been awefully horrific to his fellow man. This ‘noble savage’ idea does a great disservice to history and to the furtherance of civilization.

When my mother and I see someone in the news that has done something horrible to another person we both look to each other and say “their mother didn’t hold them enough”. My mom and I dont see eye to eye on many parenting topics but one thing that we both see as pretty obvious is that children need to be held and loved and snuggled and given your attention or they end up hurting people when they grow up. I’ve yet to read about a child that had all these needs met that just manifests evil without a cause. Something always triggers that evil. Ever watch a baby when they hear another baby crying? They look distressed by the crying, they do not like to hear crying. They know crying means pain, sadness, loneliness and discomfort-because those are the reasons they cry too. So when we allow children to hurt by ignoring these needs not only does that have lasting affects on the one being ignored but the children who witness the pain of the crying child see that there are people out there that don’t care about their own babies. No wonder trust and attachment are difficult to some when they see this routinely happening to their playmates. That kid might be unkind to my kid on the playground later on and that other parent might ignore my kids needs if ever they were in their care or having a play date. The message needs to be repeated and repeated until people understand that’s abuse and neglect are everyone’s problem because we exist in communities and what harms one in a group infects us all.