“A bit of stress is good for them!”

“A bit of stress is good for them!”

How many of you have heard this when it comes to sleep training? Day care? The idea that stress is actually a good thing? I’ve explained why this is wrong before, but we can add another reason to the list thanks to new research out of Germany: Acute stress reduces cognitive flexibility, even in infants. Let’s take a look at exactly what this new research can tell us about the effects of stress on the developing brain of infants and why this might matter to what is becoming a common parenting practice in “helping” sleep…

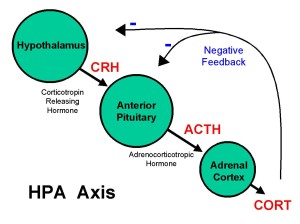

To understand the research, we have to have context and the background here is that we have quite a bit of research on the very negative effects of chronic stress on development. Children who experience chronic stress are at much greater risk of suffering a host of maladies later on. The question is what about acute stress? Acute stress is, by definition, non-chronic, but still resulting in increased cortisol and other physiological changes. In adults, small amounts of stress can be beneficial as they can increase learning, but can we take work from adults and assume the same holds for young children? Further, despite some “positives” of minor stress, we know acute stress actually results in more rigid behaviours in adults – they are unable to be flexible in their thinking which diminishes problem solving and can lead to unwanted behaviours.

In other works, I have spoken of the period of hyporesponsivity and why it is important when we discuss stress in infancy. Briefly, this period is a time when it is difficult (but not impossible) to elicit a cortical response to a stressor. It begins in early infancy (around 2 months of age) and continues for at least the first year, possibly the first three (this time frame is currently unknown). The major factor that predicts this hyporesponsivity is secure attachment and responsive caregiving. Responsive caregivers seem to buffer the child from the effects of stress and in fact the absence of such responsiveness results in increases in cortisol in children. That is, the removal of responsive caregiving when needed is a major stressor in and of itself. The fact that we have evolved to have such a period speaks to the need to keep cortisol from negatively influencing neurological development during this time, but also speaks to how the presence of stress informs the child about his or her environment.

Acute stress should therefore never be seen as “minor” for a child who is in the period of hyporesponsivity because the entire point of development and thriving is to avoid such a stress response. However, evidence for any cognitive change in children is limited simply because the research itself has not been done (not because no effects have been found). The new research, led by Sabine Seehagen from the Ruhr-Universität Bochum and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences After this condition, infants were taught a learning game involving pressing buttons to elicit lights and sounds and then having this go extinct. The key point to the test here was to see how children will respond when another button is available and the one that previously rewarded them ceases to do so. Will they remain rigid and stick with the button that worked before or will they be flexible and try something new? Key points on this methodology: The researchers found that children who had undergone the stress condition got “stuck” on the habit-acquisition button; that is, these children kept pressing that one button without trying another even though they saw that the button was no longer providing the same stimuli it did in the previous phases. On the other hand, children who had not experienced the stress-condition were less likely to persist in pressing the button that was part of the habit-acquisition phase. Interestingly, the change was most noticeable over time. Infants in the stress-condition increased the proportion of time they pressed the habituated button over the 30s of test time whereas the other infants decreased the proportion of time pressing that button (43 to 64% versus 57 to 18%). The take-home seems to be that acute stress has a similar impact on infants as it does on adults. Namely, it inhibits our ability to think flexibly which is intricately linked to our problem solving abilities. Is this study the final word on the issue? Like any new study, of course not. This is a preliminary study and should be viewed as such. An important one, mind you, but still preliminary. The methodology was appropriate and because of the cost of assessing cortisol, the sample of 26, though it might seem low, is actually in the range of normal for this type of work. Notably, the findings fit within the context of what we know about the effect of acute stress on adult cognition (which is more robust) which adds more credence to the findings, but it absolutely should be replicated before deciding how much weight should be given to it, though it certainly should not be dismissed because of its preliminary nature. How can we relate this to sleep training? I don’t know anyone who says that extinction sleep training is not at all stressful on the infant. If they believe that, they’re insane. The stress of sleep training is, at a minimum, acute stress (it can be long-term as there are families who report using this method for over a month at a time[2]). Distress during extinction sleep training is likely far higher than what was experienced in this particular study, as in this study infants were crying only around 19% of the time. And if your child isn’t crying in your “sleep training”, then it’s not extinction sleep training, now is it? Isn’t a lack of sleep even worse for cognitive development than acute stress? This is hard to answer because we know that severe sleep deprivation has both short-term and, when chronic, long-term implications; however, much of what parents report as “sleep problems” for their infants and toddlers are not actually problems[3]. They are biologically normal patterns. Because they are biologically normal, we would not expect this to have any negative effects on cognitive development. Note that this does not mean that it is not a problem for the parent which is why we have gentle ways to help guide infant sleep when absolutely necessary, but at no point is intentionally stressing a child the appropriate response. When there is a severe problem with sleep, it is best to look for the underlying cause because sleep in and of itself is not a problem – it’s a basic function, like eating, which is highly variable between people but is not something we need to “teach”. Our children will eat and eat healthy foods if we present them with those options. Sometimes the problem is simply that parents have an environment that is not conducive to sleep, such as having screens on before bed or lights that aren’t dimmed, but sometimes it’s a health issue that impedes sleep and medical attention is necessary. (Note that things like nursing to sleep and cuddling and cosleeping are not “bad habits” that need to be avoided or that hurt sleep.) However, again, there is no need to utilize extinction sleep methods that cause acute stress on top of whatever else is causing sleep disruptions. As I often explain to families, when your child is sick with the flu and not eating, we don’t treat the not eating as the problem and force feed them to “teach them to eat”. We look for the cause of not eating – the flu – and treat that knowing that the eating will resolve itself when the flu is taken care of. Thus, the argument that we must prioritize sleep over all else (which is what extinction sleep training does) ignores these key points and when we consider the additional effect of this rigidity in cognition, it should be clear that this is not the way to help when there are sleep problems. You can find other ways to help your children gently. Does this say anything about child care? It is entirely possible that this speaks to why we see externalizing behaviours in children who have spent extended periods in daycare, particularly low-quality daycare. As I have written on here, the research on stress and daycare is clear that it is an acute stressor for many infants and children, but this is mediated by quality of daycare. If this is the mechanisms by which we’re seeing negative outcomes associated with daycare, it means we have even more reason to ensure that all children are provided responsive caregiving options. What questions remain? The questions that remain, though, are equally important: _________________________

I read the article but I am still not really convinced if the research paper you discuss can tell us anything meaningful about sleep training, I understand that extinction sleep training is a controversial topic and I understand that parents want to avoid it solely because it does not fit their parenting philosophy or they feel too distressed when their infant cry, etc. These are completely valid reason to ditch sleep training. However, my problem with the fierce opponents of sleep training is that they are not able to offer any solid evidence to support their claims on long-lasting negative consequences of sleep training for a baby. All evidence that I see is based on conjectures and extrapolation, and this post makes such an attempt too. So far, no research study showed such negative long-term consequences (including the newest study form 2016 in Pediatrics). Obviously, all studies have their limitations and definitely such studies do not prove that sleep training is perfectly safe. The study of Middlemiss from 2012 that claims that extinction sleep training leads to mother-infant asynchrony has too many problems to tell us anything about sleep training too.

I guess my point is that a) the discussed research paper tells us nothing meaningful about sleep training, and b) to know more about sleep training we actually need more research on sleep training specifically.

Sorry for the delay – holidays got in the way 🙂

I understand your concern. In fact, there is a chapter in my ebook that deals with the evidence and my basic conclusion is that we don’t have a smoking gun, we do have lots of circumstantial evidence that CIO and CC are risky, and that the claims they are “safe” don’t hold up at all. Now, the research on long-term outcomes is atrocious. If you want to say Middlemiss has too many problems (which I agree – it’s a preliminary study and should be treated as such), the two studies (including the Pediatrics 2016 study) have just as many and in both cases, have fatal methodological flaws that prohibit the researchers from making the conclusions they have. You can read my summaries of each of those on this site.

Now, this conjecture is here really in response to statements I have seen recently from others making the claim that there is no negative effect of acute stress when it comes to sleep training. This research counters that bold statement that parents need not worry about any negative effect. In fact, the stress in this study was far less than an infant would experience in CIO, so the idea that acute stress is a-okay just doesn’t hold water. I hope that clarifies the issue.

And yes, I wholly agree that we need more research on sleep training specifically. Though I will be the first to say that the picture is unlikely to be anything but clear-cut and that means massive studies with lots of subgroups. It’s going to be difficult.

Subscribing.