As seems to always be the case, when a new article comes out suggesting breastfeeding “isn’t all that”, the media pounces on it. Tons of articles crop up reminding us that the “benefits” of breastfeeding either aren’t all that great or that we’re ignoring real risks about breastfeeding. Well, another new article has done just that and grabbed headlines in most news outlets, proclaiming real risks associated with breastfeeding

Well, the research looks at serum levels of perfluoritnated alkylates substances (PFASs) in children and compares rates of these chemicals based on breastfeeding exclusivity and duration. The study, conducted jointly by researchers at Harvard University’s Chen School of Public Health, the University of Copenhagen, the University of Southern Denmark, and the Faroese Hospital System, examined levels of these chemicals (which we don’t want in our system, discussion below) in a cohort of Faroese children at ages 11 months, 18 months, and 5 years and looked at how these levels were influenced by breastfeeding practices. There were data for a total of 81 children. (Notably, the researchers included birth “serum levels”, but this was based solely on maternal values that were extrapolated to the infant. There is research on how these chemicals cross the placental barrier which was used to make the calculation herein, but this birth number remains controversial because it was not obtained directly from the infant and thus is not actually a serum level, but an estimate.) The researchers found that the duration of exclusive breastfeeding increased the concentrations of several PFASs by 16-31% per month of exclusive breastfeeding. Notably, partial and no breastfeeding had very little effect on the serum levels of various PFASs. The models controlled for previous serum levels, ingestion of whale meat (a prominent source of PFAS exposure in the Faroe Islands), and child sex and sex by breastfeeding interactions.

After weaning, children generally showed steady decreases in their levels of PFAS in accordance with half-life measurements found in previous research. Furthermore, the levels reached in these infants at 11 (when most peaks were found, though it may have been higher during breastfeeding) were often higher than that of their mother. The transmission of these chemicals via breast milk (as they are not found in formula) suggested to at least one of the authors – Dr. Grandjean – that we should think twice about promoting breastfeeding for any duration after 3-4 months, and especially about promoting exclusive breastfeeding. For the authors taken as a whole (i.e., what was written in the article), the concern is about the degree to which we are finding these chemicals in our environment and how these chemicals build-up in the human body over development. However, the media focus has been exclusively on the “risk” associated with breastfeeding which is what I will focus much of the Q&A on below.

Let me start here by saying that this research area into PFASs is not my expertise. I have read more than I ever anticipated in the last couple days on this and have tried to synthesize it all as best I can. Though I understand the research on it, I admit to being frustrated at how mixed and of poor quality a lot of it is. I had always hoped that we were doing better than this at researching the effects of chemicals in our environment. Because of my limited time and exposure on this topic, I would welcome any comments from those with more experience in this field, especially those that may be able to explain why the research is as poor as it is (and note that it’s not just me saying that, but was also the conclusion of a systematic review on the topic of PFASs).

What are PFAS and why should we care?

They are chemicals used to make all sorts of industrial products and they enter our bloodstream due to our use of these chemicals and through our diet and drinking water. One study found that vaccine uptake (specifically tetanus and diphtheria) was linked to PFAS exposure in that the vaccine antibody concentrations were found to be lower in those children with higher levels of serum-PFC (two specific long-chain perfluorinated alkylates which have been limited in use in recent years)[2]. Animal models have led to concerns about the health effects of these chemicals on humans, though epidemiological research is still scarce. Many regions have put and are putting restrictions on the use of PFASs in manufacturing in order to limit their use and thus overall human exposure, especially in terms of the amount allowed in drinking water. Many individual states[3][4] and the European Food Safety Administration[5] have recommended exposure limits for drinking water, especially for the longer-chain versions which seem to have longer half-lives.

Beyond this, we actually don’t know the health risks associated with their use, though the Environmental Protection Agency states that, “significant adverse effects have not been found in the general human population” despite finding high levels of PFASs in humans. One review of the epidemiological research done to date concluded that “data are limited to draw firm conclusions regarding the role of PFOA [a PFAS] for any of the diseases of concern”[6]. However, because of the long half-life, very long-term effects are currently unknown, animal models show effects of PFAS toxicity, and the fact that these chemicals continue to build up in our system through repeated exposure could mean that there are risks we are unaware of. Like we say about things like crying-it-out, it seems the issue here is that more research is needed, not that we have all the research we need and a conclusion can be reached. Even the review of the epidemiological research acknowledges that the research on these chemicals “remains limited in volume and quality”. It seems the take-home message here needs to be not on breastfeeding, but on the overall effect of these chemicals on humans and curbing their use more generally if found to be detrimental to our health.

If the findings hold, shouldn’t we limit breastfeeding or at least the promotion of it, as suggested by Dr. Grandjean?

No, not at all and there are a couple reasons for this. First and foremost, the hypothesized concern in terms of PFAS exposure is with respect to immune function based on research on the uptake of certain vaccines[2]. However, as we know from myriad other studies, immune function is improved with extended breastfeeding. In fact, as I’ve covered here and here, the more research looks at breastfeeding in an evolutionary or biological manner which includes exclusive breastfeeding for approximately six months and then continues breastfeeding to age 2 or longer, the riskier formula looks with respect to health and long-term outcomes. If these chemicals were having such a strong immune effect to suggest reduced breastfeeding, we would expect to see better outcomes based on partial breastfeeding or not breastfeeding at all when instead we find the opposite in our research with humans.

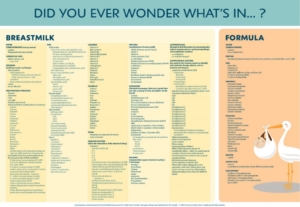

Second, the research makes a good case for breast milk being one of the most prominent ways in which infants obtain levels of PFASs in their system and the levels found were high, though we have no research proving any associated health problems in humans with the levels we are seeing (though there are studies that have found health problems in animal models[7], but as mentioned, epidemiological research has not found this to be the case in humans[6]). Add to this, although formula does not contain high levels of PFASs, in most Western nations one of the primary sources of exposure to PFASs is through our drinking water (as opposed to the Faroe Islands)[6]. Well, guess what is used to mix with formula? Thus, the question remains about how beneficial it would be to use formula mixed with PFA-contaminated water which the infant ingests directly instead of breast milk which at least also contains all sorts of immune-enhancing elements (see here), even for just these particular chemicals. And of course, all of this ignores the myriad other ingredients found in formula that may be hazardous for infants or that may be influencing their immune reactions to various diseases (and why we see the effects of breastfeeding that we do). Thus, when we take a look at the totality of the evidence, there is no way that it even comes close to saying that the risks of breastfeeding with respect to these particular chemicals outweighs the risks of formula across myriad health outcomes and the presence of other chemicals.

Notably, in the research paper itself, none of the researchers actually suggest that breastfeeding should be limited; however, as mentioned, Dr. Grandjean has made comments to the press about this fact. As he was quoted as stating in one article, “Breast feeding provides a net benefit during the first three or perhaps four months of exclusive breastfeeding. The benefits appear rather small after that.” Yet the benefits in a Western context appear greatest with greater exposure to breast milk (in developing nations, the effects are so very great with any breast milk). Oddly, when he discusses the safety of drinking water, he ignores research on how not all Western families have access to safe drinking water, but also that drinking water seems to be one of the primary sources of these PFASs for individuals in Western nations, even though this is mentioned in the introduction to this paper and by as covered by other research[6]. Of course, his focus for his entire career is on these particular chemicals and thus he seems unable to look at the entire picture when it comes to anything pertaining to these chemicals.

Notably, in the research paper itself, none of the researchers actually suggest that breastfeeding should be limited; however, as mentioned, Dr. Grandjean has made comments to the press about this fact. As he was quoted as stating in one article, “Breast feeding provides a net benefit during the first three or perhaps four months of exclusive breastfeeding. The benefits appear rather small after that.” Yet the benefits in a Western context appear greatest with greater exposure to breast milk (in developing nations, the effects are so very great with any breast milk). Oddly, when he discusses the safety of drinking water, he ignores research on how not all Western families have access to safe drinking water, but also that drinking water seems to be one of the primary sources of these PFASs for individuals in Western nations, even though this is mentioned in the introduction to this paper and by as covered by other research[6]. Of course, his focus for his entire career is on these particular chemicals and thus he seems unable to look at the entire picture when it comes to anything pertaining to these chemicals.

All in all, the focus here really ought to be on the effects of these chemicals on our health and development with an emphasis on lowering our exposure to them full stop. This means making companies more responsible for what is leaked into our environment and send into our homes, making mothers aware of how they are exposed to these chemicals so they can attempt to limit their own exposure and thus that of their infants, and more generally the effects of these chemicals on our ecosystem and environment which has great impact on our health.

Shouldn’t we be very concerned simply about the fact that these infants surpassed their mothers’ levels of these chemicals?

On the surface, yes, it seems worrisome that our children are exposed to greater doses of PFASs than us adults. However, this ignores that research on typical children have shown that they regularly have higher levels than adults[8] so infants passing their mothers isn’t actually an odd thing. The effects on development and the exposure at a young age is what deserves more research and frankly, the focus should be on how these chemicals enter our food chain and water systems. If this research leads to better regulations, that’s a good thing, though no such regulations on breastfeeding would make sense, as covered above.

The study was conducted in the Faroe Islands, how does this compare to other Western nations?

It is difficult to tell if there’s much of a difference as PFAS have permeated the world thanks to their bioadditive nature and the fact that they have hit our water sources. Researchers suggest that the levels of PFASs are similar in adults in the Faroe Islands and the United States[2]; however, the means of exposure seems to be different. In the United States (and other developed, Western nations), exposure is primarily through industrial products that contain these PFASs and our drinking water (where PFASs have infiltrated due to industrial pollution) whereas in the Faroe Islands it is reported that the majority of the exposure is due to an oceanic diet, specifically whale meat as PFASs are bioadditive[9]. That is, as the chemicals enter the water, fish and other water mammals ingest the chemicals and infiltrate their meat and one of the primary sources of food in the Faroe Islands is whale meat (indeed, over 70% of the children in the current sample had ingested whale meat by the time they were 5 years of age).

The question here becomes how the maternal ingestion or exposure to PFASs influences the transmission to baby, if at all. As PFAS exposure comes from a dietary source in the Faroe Islands, it is possible that more PFASs are transmitted via breast milk than in other Western nations where the primary exposure is from other sources, like industrial products, as we know that ingestion of food items also pass through to the infant relatively quickly, as in the case of breastfed infants reacting to allergenics or dairy in the mother’s diet[10][11]. However, as we also receive doses of PFAS from drinking water (especially some specific PFAS, such as PFOA), it may be that the difference in locale is meaningless; however, the fact that our source comes from water which is used in formula preparation does suggest a potential route to the formula-fed baby in an industrialized Western nation with higher levels of PFASs in the drinking water.

One additional concern in our Western world is how much exposure via other means impacts our infants. That is, the Faroe Islands and the specific small fishing village used in the PFAS research on humans by this research group to date is known to get most of its exposure via their diet. However, our infants in Western nations are exposed to myriad chemicals in all of the various industrial products we use around the house and in our society. How do these types of exposure influence infant serum levels? This is again why I believe the focus needs to be on the overall effect of these chemicals and not this one means of transmission, namely breastfeeding.

The data was collected 15 years ago. Does this change anything?

Yes, absolutely. Why? Well, for starters, more limits on the use of some of these PFASs have been enacted in the last 15 years, such as regulations on acceptable drinking water levels. This regulation means that likely we are exposed to lower levels these chemicals than before. Second, because the longer-chain PFASs were found to possibly be harmful thanks to animal research, replacements have been found by many of the major users of these chemicals[12][13]. For example, in 2005 the US Environmental Protection Agency declared that PFOA, one specific PFAS, was “likely to be carcinogenic in humans”[14] and we have since seen a drastic decline in the use of this specific PFAS in manufacturing. These changes have meant that overall levels of some PFASs have actually decreased in the population of the years[12-13] and with this decrease, it is possible that the levels our infants are reaching are not of concern from a developmental or health perspective.

Who funded this research?

Based on the comments from Dr. Grandjean, many people were convinced that the study itself was funded by formula manufacturers. This is not the case. Peer-reviewed research must list all funding sources and for this study, this is the funding:

“This study was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH (ES012199); the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (R830758); the Danish Council for Strategic Research (09-063094); and the Danish Environmental Protection Agency as part of the environmental support program DANCEA (Danish Cooperation for Environment in the Arctic).” [1]

No formula companies. It is also worth noting that these findings are part of a greater research study into PFASs and this sample has been used to report on things like half-life levels and reactions to vaccines based on serum-PFAS. Thus, the funding represents an effort to better understand the overall nature of how these specific chemicals influence our health and environment, and as such, are not a knock at breastfeeding. That seems limited solely to one of the authors with his own views on breastfeeding.

Are there other limitations we should be aware of?

The study has quite a few limitations worth mentioning. As already mentioned, the serum-PFAS for birth was not actually measured, but rather estimated from maternal levels taken during pregnancy. This limits our ability to know how much birth levels really influence the trajectory. Second, mother’s whale intake was not measured or assessed. Though it is unlikely there is too much variability, it would speak to how much mom’s diet influences the amount of PFASs being passed on through her breast milk (and thus how much we need to be aware of what we, as breastfeeding mothers, are ingesting). Third, there was substantial attrition in the original study population and those who agreed to these blood samples and no effort was made to ensure the samples were similar on background which may also influence how PFASs accumulate in the body (i.e., there may be a biological factor at play that’s being missed). Fourth, we the reader are not given the average exposure levels of PFASs for the entire group, only a subset of 12 children, thus it is unclear how these percentage increases affect overall levels relative to any concerns about toxicity. Fifth, no measures of serum-PFAS were assessed during the breastfeeding period and by the time of the first assessment, no child was exclusively breastfeeding and it is unclear what partial breastfeeding entailed in the entire group (e.g., does this mix formula with the addition of solids combined with breastfeeding?).

Perhaps most importantly, the researchers did not measure any level of immune functioning or health outcomes in the children of interest. This means that the red flags being waved about the increases in these levels are purely speculative and based on equally questionable research looking at antibody responses to two specific vaccines[2]. It is a case in which the findings seem to be oversold, especially when there are public declarations against breastfeeding which also happens to counter tons of other research on the immune-benefits of breastfeeding. Finally, this lack of evidence counters other research on how the immunoprotective components of breast milk actually help counter any effect of a chemical or contaminant that may enter the infant’s system via breast milk (see here for a full discussion in an open-access journal article).

So, do we need to worry about chemicals in breast milk at all?

Yes!!! One thing I really hope hasn’t come across here is that we can close our eyes and ignore the issue of chemicals in our environment and their impact on our health. Although we should not listen to someone suggest we ought not breastfeed because breast milk can transmit certain chemicals to our infants, we also shouldn’t ignore the very real effects that our environment has on our health and that of our families. Being aware of what chemicals are found in your drinking water or the foods you eat are essential ways to knowing what both what you are ingesting and to what you may be passing on to your child. As has been found throughout research, there will only be certain select cases in which what we ingest is so clearly contraindicated for breastfeeding that we need to abstain from such a biologically normal act and replace it with something man-made which also contains chemicals (whether one chooses formula is an entirely different subject).

I do hope that this research gets more people thinking about our exposure levels to chemicals that are thought to be toxic to humans and for which we really have a paucity of research. It is not a topic to be taken lightly and one that is necessary for the future health of our children, our environment, and ourselves. Let that be the take-home message and hope policy makers are taking note.

____________________________________

[1] Mogensen UB, Grandjean P, Nielsen F, Weihe P, Budtz-Jørgensen E. Breastfeeding as an exposure pathway for perfluorinated alkylates. Environ Sci Technol 2015; DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02237. [2] Grandjean P, Andersen EW, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Nielsen F, Molbak K, Weihe P, Heilmann C. Serum vaccine antibody concentrations in children exposed to perfluorinated compounds. JAMA 2012; 307:391–397. [3] Post GB, Louis JB, Cooper KR, Boros-Russo BJ, Lippincott RL. Occurrence and potential significance of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) detected in New Jersey public drinking water systems. Environ Sci Technol 2009; 43:4547–4554. [4] Minnesota Department of Health. Health Risk Limits for Perfluorochemicals. In Report to the Minnesota Legislature. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Health; 2008. [5] European Food Safety Authority. Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food chain on Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and their salts. The EFSA Journal 2008; 653:1–131. [6] Steenland K, Fletcher T, Savitz DA. Epidemiological evidence on the health effects of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 1100-8. [7] Seacat AM, Thomford PJ, Hansen KJ, Olsen GW, Case MT, Butenhoff JL. Subchronic toxicity studies on perfluorooctanesulfonate potassium salt in cynomolgus monkeys. Toxicol Sci 2002; 68:249–264.DeWitt JC, Peden-Adams MM, Keller JM, Germolec DR. Immunotoxicity of perfluorinated compounds: recent developments. Toxicol Pathol 2012; 40:300–311.

[8] Kato K, Calafat AM, Wong LY, Wanigatunga AA, Caudill SP, Needham LL. Polyfluoroalkyl compounds in pooled sera from children participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2002. Environ Sci Technol 2009; 43:2641–2647. [9] Weihe P, Kato K, Calafat AM, Nielsen F, Wanigatunga AA, Needham LL, Grandjean P. Serum concentrations of polyfluoroalkyl compounds in Faroese whale meat consumers. Environ Sci Technol 2008, 42:6291–6295. [10] Kahn A, Mozin MJ, Casimir G, Montauk L, Blum D. Insomnia and cow’s milk allergy in infants. Pediatrics 1985; 76: 880-4. [11] Tanpowpong P, Broder-Fingert S, Katz AJ, Carargo Jr CA. Age-related patterns in clinical presentations and gluten-related issues among children and adolescents with celiac disease. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 2012; 3: e9. [12] Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999–2000. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115:1596–1602. [13] Olsen GW, Mair DC, Reagen WK. Preliminary evidence of a decline in perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) concentrations in American Red Cross blood donors. Chemosphere 2007; 68: 105–111 [14] U.S. EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) Draft Risk Assessment of the Potential Human Health Effects Associated with Exposure to Perflouroctanoic Acids and Its Salts. 2005

[…] Lees een gedegen bespreking van dit onderzoek hier: Chemicals Found in Breast Milk: Is It Enough to Negate the “Benefits”? | Evolutionary Parenting …. […]

Good analysis. No one wants to see pollution in breastmilk, yet we allow non-stick cookware to be sold and shed PFAs, etc etc,. Sandra Steingraber’s books should be read by everyone concerned about breastmilk pollution. But the MAJOR problem here is the ignorance of almost everyone about infant formula’s inadvertent and inevitable contaminants and inescapable problems (yes, even the newest ones). Please read my new book, Milk matters: infant feeding and immune disorder, to put this whole issue into perspective. Website : http://www.infantfeedingmatters.com

Once you’ve read my book, write to me if you believe that there is any possible way that infant formula could be better than breastmilk, however much breastfeeding raises PFA levels (and lowers them in the mothers, btw, perhaps reducing risks of cancer.)

Yes, the media jumping on the catchy news of “breastfeeding isn’t good” frenzy is not helping things. However, neither are these type of articles that have one goal in mind: defending breastfeeding at all costs and pursuing a discourse that only leads in that direction. Conclusions like “there is no knowledge of the dangers of PFASs’ so “‘it’s not that bad” are just concerning (and no offence intended for the author who does bring some good points forward). There have been several studies showing all kinds of toxins showing up in the breast milk: flame retardants, BPA, phthalates, mercury and others. What is the safe level of these toxins in breast milk? ZERO. That’s the safe level. Zero. They are not supposed to be there. So should a mother stop breastfeeding? No, the first months are crucial. But should supplementing be considered? Yes, it should actually.

Actually not based on the long-term research that consistently finds that *longer* term breastfeeding offers more benefits than shorter-term breastfeeding. Also that many of these chemicals are found in formula as well given the process it takes to produce formula. Then there’s the issue of our drinking water. I agree that we need to be very aware of how these chemicals enter our environment, but there is NO research supporting the idea that supplementation is somehow better and in fact, the research we have would suggest breastfeeding still remains better for the overall health of the infant.

Also, I’m not sure where I said that “it’s not that bad” as opposed to pointing out we need more research.

[…] commentary on this study, by Dr. Tracy Cassels, can be found at the Evolutionary Parenting site, from which I will only excerpt a brief section of a long, well-written dissection of the […]

[…] https://gku.flm.mybluehost.me/evolutionaryparenting.com/chemicals-found-in-breast-milk-is-it-enough-to-negate-the-benefits/ […]

[…] This abridged article was written by Tracy Cassels, PhD, and originally appeared on her blog, Evolutionary Parenting […]