To view this in Hebrew, please click here thanks to Idan Melamed

One of the mantras preached by those of you trying to “save parents’ sleep”‘ is that a child who has all of her needs met is only crying in order to manipulate you. You claim the crying is bad behaviour that needs to be stomped out – you need to show the baby who is in charge and make sure that they realize that by crying, they will not get what they want. If we remember from lesson one, however, crying is typically the only form of communication that young babies have (and almost always the most readily available) and so to ignore it or to try and stomp it out is simply to cut away the child’s only way of telling you what she needs. Yet you tell parents that as long as you’ve made sure that the child’s diaper is dry, they are fed, and they are warm, that there are no other reasons to cry. Needs? Met. This allows parents to let their child cry and to ignore it (or do other rather asinine things like stay in the room looking at them but not touching them). But I have a question that I wish these experts would answer: Have you ever been fed, clothed, and dry and still been sad? Or scared? Or simply felt the need for human contact? If you answered no, you are either a psychopath or lying. The reason we can feel this way is that our needs extend beyond the physiological and arguably, for an infant, the psychological and emotional can be as important as the physiological for survival. How did you come to this very limited view of “needs” for infants? I acknowledge that there is the real fact that we do have physiological needs that must be met before we can consider the psychological and emotional. We need water and food and heat to stay alive. But there’s more, and I can admit that you didn’t do it on your own. Sadly you seem to have taken a few more pages from the behaviourists’ handbook, much to babies’ collective despair…

One of the mantras preached by those of you trying to “save parents’ sleep”‘ is that a child who has all of her needs met is only crying in order to manipulate you. You claim the crying is bad behaviour that needs to be stomped out – you need to show the baby who is in charge and make sure that they realize that by crying, they will not get what they want. If we remember from lesson one, however, crying is typically the only form of communication that young babies have (and almost always the most readily available) and so to ignore it or to try and stomp it out is simply to cut away the child’s only way of telling you what she needs. Yet you tell parents that as long as you’ve made sure that the child’s diaper is dry, they are fed, and they are warm, that there are no other reasons to cry. Needs? Met. This allows parents to let their child cry and to ignore it (or do other rather asinine things like stay in the room looking at them but not touching them). But I have a question that I wish these experts would answer: Have you ever been fed, clothed, and dry and still been sad? Or scared? Or simply felt the need for human contact? If you answered no, you are either a psychopath or lying. The reason we can feel this way is that our needs extend beyond the physiological and arguably, for an infant, the psychological and emotional can be as important as the physiological for survival. How did you come to this very limited view of “needs” for infants? I acknowledge that there is the real fact that we do have physiological needs that must be met before we can consider the psychological and emotional. We need water and food and heat to stay alive. But there’s more, and I can admit that you didn’t do it on your own. Sadly you seem to have taken a few more pages from the behaviourists’ handbook, much to babies’ collective despair…

Behaviourism

For many years, the dominant psychological theory was the behaviourist view headlined by John Watson, B.F. Skinner, and Edward Thorndike. Briefly touched upon in lesson one because of behaviourists’ belief in conditioning, behaviourism also held the view that all infants were born with a blank slate. As John Watson himself stated in his famous 12 infants quotation:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select — doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.[1]

What does this have to do with needs? The basis of behaviourism is that there is no such thing as introspection; mental states were things that were irrelevant without behaviour[2], or as Skinner claimed, mental states were rejected outright[3]. Well, the blank slate approach implies that infants’ psychological capabilities are diminished; if they can be fully molded, there isn’t much there to begin with. The failure of the infant to outwardly demonstrate psychological phenomena was taken as proof that they simply did not occur. If there are no psychological states to contend with, and only learning, then the only needs an infant can have are those that pertain to the physiological. (It is worth noting that not all psychologists or even behaviourists believed this, but that this became the prominent view that received much of the attention of the masses. Because of this, and because conditioning does work in the behaviourist sense, it seems to have been the basis of much parenting advice.)

Infant Psychological States

We now know that the idea that infants lack psychological or emotional states, even complex ones, is false. While infants lack the meta-knowledge most adults have about their own psychological states, both common sense and research have demonstrated that infants experience these states regularly and that a parent’s understanding and responsiveness to them has far-reaching effects. In fact, even the behaviourists would have to acknowledge that infants can experience emotions such as fear, as John Watson’s Little Albert Experiment (discussed in Lesson One) conditioned the baby to become fearful of the white rat[4]. So if infants can have emotional states, what role do parents play? Those parents who have an understanding of the reflexive self (the notion that we can be aware of mental events, emotions, etc. and this is distinct from actually experiencing these emotions) and use this understanding in their parenting have children who are more securely attached and who show greater mental awareness in later years than those who do not[5]. That is, treating a child as though he has mental and emotional states will lead to greater attachment and his own awareness of his mental states (this shouldn’t be a big surprise, but for some reason this isn’t a commonly held view).

We now know that the idea that infants lack psychological or emotional states, even complex ones, is false. While infants lack the meta-knowledge most adults have about their own psychological states, both common sense and research have demonstrated that infants experience these states regularly and that a parent’s understanding and responsiveness to them has far-reaching effects. In fact, even the behaviourists would have to acknowledge that infants can experience emotions such as fear, as John Watson’s Little Albert Experiment (discussed in Lesson One) conditioned the baby to become fearful of the white rat[4]. So if infants can have emotional states, what role do parents play? Those parents who have an understanding of the reflexive self (the notion that we can be aware of mental events, emotions, etc. and this is distinct from actually experiencing these emotions) and use this understanding in their parenting have children who are more securely attached and who show greater mental awareness in later years than those who do not[5]. That is, treating a child as though he has mental and emotional states will lead to greater attachment and his own awareness of his mental states (this shouldn’t be a big surprise, but for some reason this isn’t a commonly held view).

Further evidence highlighting infants’ psychological and emotional states and the relationship to parent behaviour comes from the Face-to-Face Still-Face paradigm[6]. In this paradigm, parents are face-to-face with their infants, engaging with them, when the parent stops and maintains a still face, expressing no emotion, and then finally parents resume facial interaction. During the still-face component of the paradigm, infants display increases in negative affect including withdrawl, grimaces, grasping at the self, and crying (amongst others). Why the infant changes his or her behaviour is of importance here and there are competing hypotheses. One is that the parent is now violating the infants’ expectations for behaviour and becomes distressed. A second one is that the mother has stopped providing important sensory input that the child needs in order to regulate his own social and affective state[7]. Research supports this second interpretation as simply providing touch during this still-face episode reduces the distress that the infant typically experiences[8][9][10].

Further evidence highlighting infants’ psychological and emotional states and the relationship to parent behaviour comes from the Face-to-Face Still-Face paradigm[6]. In this paradigm, parents are face-to-face with their infants, engaging with them, when the parent stops and maintains a still face, expressing no emotion, and then finally parents resume facial interaction. During the still-face component of the paradigm, infants display increases in negative affect including withdrawl, grimaces, grasping at the self, and crying (amongst others). Why the infant changes his or her behaviour is of importance here and there are competing hypotheses. One is that the parent is now violating the infants’ expectations for behaviour and becomes distressed. A second one is that the mother has stopped providing important sensory input that the child needs in order to regulate his own social and affective state[7]. Research supports this second interpretation as simply providing touch during this still-face episode reduces the distress that the infant typically experiences[8][9][10].

I would argue we are forced to accept the notion that not only do infants have psychological states, but that the way in which we interact with our children will affect these states either positively or negatively. Going forward, we should consider what types of psychological states are relevant for needs. Most commonly we refer to an infant’s distress as requiring comfort, and thus most of what I will cover will pertain to this. However, I would be remiss to suggest that that’s all there is. Infants require social stimulation in any emotional state, as the Face-to-Face Still-Face paradigm suggests; these infants are happy while interaction and then work hard to try and get their caregiver to return to this state of social interaction. Interestingly, in this paradigm, even after the resumption of interaction, the infant’s arousal pattern remains mixed – while the positive affect rebounds quickly, the negative affect does not disappear for some time, with an increase in fussiness and crying because of the brief negative event[11]. While this will prove to be more important in a later lesson, what this demonstrates is that the need to reduce negative affect in an infant can take time – it is not an instantaneous response.

What are our Human Needs?

Even during behaviourism’s reign in psychology, a theory of human development was taking place that would have equally far-reaching effects. Abraham Maslow, thinking along the lines of Freud and Erickson, set out to study the developmental stages of human growth psychologically-speaking. Interestingly and relevantly, his focus lay in the study of human needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs emphasized the view that as humans we have levels of needs and only once one level is satisfied can we have the impetus to fulfill the next[12][13]. Generally interpreted in pyramid form, the levels are as follows (starting from the bottom, or most basic, to the top):

a) Physiological: breathing, food, water, sex, homeostatis, excretion

a) Physiological: breathing, food, water, sex, homeostatis, excretion

b) Safety: personal and financial security, health, illness or accidents

c) Love and Belonging: the primary relationships in one’s life (family, friendship, romantic) – note that in childhood this need may come before safety

d) Esteem: respect from others, accepted and valued

e) Self-Actualization: realizing and fulfilling one’s full potential

The first four are referred to as deficiency needs because they are, in Maslow’s view, necessary. While the first is required to simply survive as an organism, the second through fourth are also necessary and Maslow argued that without them, individuals will feel psychologically at odds (including tension, anxiety, depression). Other researchers have tested this theory and found considerable support, suggesting that our well-being is intricately tied to our ability to fulfill these needs[14].

While there have been criticisms of Maslow’s hierarchy[15], no criticism has suggested that these basic needs are simply not needs. For example, there has been criticism about the nature of the hierarchy with some suggesting that no hierarchy is needed to represent these needs, while other suggest the hierarchy is culturally dependent (and thus the third need – love and belonging – would be even more paramount in collectivist cultures). But it would be very difficult to find an individual today who assumes that humans, even infants, have no needs outside of the physical.

I hope that at this stage you can accept that the psychological and emotional needs are real and found worldwide. To assume that only the first level of physiological needs matters when dealing with a newborn ignores the research (and common sense) that demonstrates there is much more to well-being than simply being fed, dry, and not in physical pain.

Importance of Psychological and Emotional Needs

Assuming we are in agreement that physiological needs are not the only ones, the next question to address is what happens when these psychological and emotional needs are not met? Here I outline four areas of research that help demonstrate the very real and serious consequences of ignoring the psychological and emotional needs of young children and infants.

a) Orphaned Children in the Early to Mid-Twentieth Century. Our best understanding of the effects of a emotional and psychological needs not being met comes from studying individuals who grew up in such environments and comparing them to those who had those needs met. This is hard to do because you can’t just force a child to be put in a situation in which you harm them, but sadly there are situations that existed that have allowed this research to be done. For many years, infants placed into institutionalized care were cared for in the most basic of ways – they were held to be fed, they were changed and kept dry, some had mobiles to look at – but they were rarely socially stimulated and certainly never had their comfort needs met. They cried and were left to cry in part because of the belief that only their physical needs needed to be met.

a) Orphaned Children in the Early to Mid-Twentieth Century. Our best understanding of the effects of a emotional and psychological needs not being met comes from studying individuals who grew up in such environments and comparing them to those who had those needs met. This is hard to do because you can’t just force a child to be put in a situation in which you harm them, but sadly there are situations that existed that have allowed this research to be done. For many years, infants placed into institutionalized care were cared for in the most basic of ways – they were held to be fed, they were changed and kept dry, some had mobiles to look at – but they were rarely socially stimulated and certainly never had their comfort needs met. They cried and were left to cry in part because of the belief that only their physical needs needed to be met.

But a strange thing was happening… babies were dying. In the early part of the twentieth century, it was reported that close to 90% of infants in orphanages were dying, and the 10% who weren’t were getting some type of foster care[16]. Children that didn’t die in orphanages were not in the clear, with one longitudinal study examining children who were orphans in the mid-twentieth century showing significantly more psychosocial dysfunction (i.e., mental health problems), stress, and chronic illnesses than matched controls[17]. Notably, as soon as orphanages provided comfort as part of the basic care provided to infants, mortality and morbidity rates dropped dramatically[18].

b) John Bowlby’s Maternal Care and Mental Health[19]. At the end of World War Two, the World Health Organization became deeply concerned with what became apparent was very negative outcomes for some children in Eastern Europe. Because of Bowlby’s academic and clinical work on problem children and the effects of institutionalized care on development (for which he found mental health problems associated with a lack of psychological and emotional needs being met), he was commissioned to write a report on the mental health of homeless and orphaned children in Eastern Europe.

In this report, it was written that children need a close, warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with their mother or permanent mother substitute and that the lack of this type of relationship can have serious and irreversible mental health consequences. He noted that the social needs are not secondary to physical needs, but are equally primary as evidenced by a child’s influence in attaining social interaction. Importantly, Bowlby was one of the first to argue that the feeding relationship was not the primary way in which the mother affected her child’s well-being, but that her closeness to her child and offering of comfort was more important.

The monograph was highly criticized at the time, as many people argued that either a strong parent-child relationship is not necessary to a child’s well-being or that maternal love is not necessary. The feeding bit, however, was highly criticized at the time as many people felt that only through meeting a physiological need would there be the bond between parent and child or that as long as someone fed the child, it didn’t matter what else happened. Later work, including Bowlby and Ainsworth’s work on attachment theory, would silence many of these critics (though obviously not all), and today there is no doubt that the lack of a parental relationship or the lack of parental love results in mental health deficiencies.

c) A Two-Year Old Goes to Hospital. In 1953, James Robertson produced a short documentary on what happens to a child who has to go to the hospital and therefore suffers through maternal separation. This is a heart-wrenching film that is now shown in almost all introductory developmental psychology courses. The motivation for the film was that, at the time, visiting children at the hospital was very limited, and during his work as a psychoanalyst he observed the children’s behaviour upon separation. While the medical professionals treating the physiological problem saw young children (Robertson focused on under 3’s) protest at first, they also saw that they soon became compliant and quiet (sound familiar experts?). What Robertson observed over years of studying the children from a psychological perspective was three phases of response: Protest, Despair, then Denial/Detachment[20].

c) A Two-Year Old Goes to Hospital. In 1953, James Robertson produced a short documentary on what happens to a child who has to go to the hospital and therefore suffers through maternal separation. This is a heart-wrenching film that is now shown in almost all introductory developmental psychology courses. The motivation for the film was that, at the time, visiting children at the hospital was very limited, and during his work as a psychoanalyst he observed the children’s behaviour upon separation. While the medical professionals treating the physiological problem saw young children (Robertson focused on under 3’s) protest at first, they also saw that they soon became compliant and quiet (sound familiar experts?). What Robertson observed over years of studying the children from a psychological perspective was three phases of response: Protest, Despair, then Denial/Detachment[20].

The movie is shot to provide evidence of this trauma and centers on Laura, aged 2, who goes in for a minor operation but will spend 8 days in the hospital. If you can find the film and stand to watch it (for it will make you cry), you will witness a child who is too young to understand her mother’s absence and who cries for her mother regularly, but who is forced to face this very scary, unfamiliar, and at times painful experience on her own. She finally becomes quiet and “settles” as the doctors put it, but once her mother returns, we see that Laura never settled. She remains withdrawn, even from her mother, showing signs of having undergone a massive trauma. There is no follow-up to see how Laura does, but the film is the reason that many children’s hospitals changed their policies. Further examination of Robertson’s claims demonstrated that indeed children were suffering and thus policy changes were a must. It is worth noting that while the maternal separation was great during these periods for these children, it was not absolute, and in many cases the children were expressing the psychological and emotional need for comfort when they were fed, dry, and not in physical pain; they were simply scared.

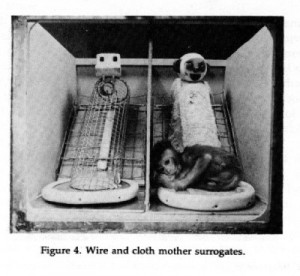

d) Harry Harlow’s Monkeys. Because of John Bowlby’s work and Robertson’s film and work on the loss of maternal care, Harlow decided to further study what is the crucial element that mothers provide that was leading to these very negative outcomes found by Bowlby and Robertson. In studies that would never pass an ethics review today, Dr. Harlow was motivated to discover the relative weighting of the feeding element of the maternal and the comfort. He was drawn to this because of Bowlby’s monograph and what Robertson’s documentary showed.

To do this, Harlow separated young monkeys from their mother’s at birth and provided them with two surrogate mothers. In the most telling experiment (others were all variations on this and provided the same evidence), one was a wire monkey who provided food for the baby monkey while the other was a cloth mother designed to offer some form of contact comfort. Many people expected the monkeys to spend all of their time with the wire mother who offered food, but the exact opposite happened. While the monkeys went to that mother when they needed feeding, they spent the vast majority of their time with their cloth mother. And when any type of negative or scary event happened, they clung to their cloth mother for protection and comfort. When the monkeys were brought to new surroundings with their cloth mother, they used “her” as a base from which to explore. If either no mother or the wire/food mother was there instead, the monkeys became erratic, upset, and/or violent. They were afraid of their surroundings and had no secure base from which to explore; only the surrogate ‘comfort’ mother provided that psychological foundation. In short, despite having their immediate physiological needs met by the wire monkey, only the mother that provided comfort (however shabbily) provided the necessary psychological comfort that allowed the monkeys to handle new situations.

To do this, Harlow separated young monkeys from their mother’s at birth and provided them with two surrogate mothers. In the most telling experiment (others were all variations on this and provided the same evidence), one was a wire monkey who provided food for the baby monkey while the other was a cloth mother designed to offer some form of contact comfort. Many people expected the monkeys to spend all of their time with the wire mother who offered food, but the exact opposite happened. While the monkeys went to that mother when they needed feeding, they spent the vast majority of their time with their cloth mother. And when any type of negative or scary event happened, they clung to their cloth mother for protection and comfort. When the monkeys were brought to new surroundings with their cloth mother, they used “her” as a base from which to explore. If either no mother or the wire/food mother was there instead, the monkeys became erratic, upset, and/or violent. They were afraid of their surroundings and had no secure base from which to explore; only the surrogate ‘comfort’ mother provided that psychological foundation. In short, despite having their immediate physiological needs met by the wire monkey, only the mother that provided comfort (however shabbily) provided the necessary psychological comfort that allowed the monkeys to handle new situations.

Taken together, the research areas demonstrate that the failure to provide for infants’ psychological and emotional needs can result in dramatic social deficits, physical problems later in life, and even death. I know most of you out there will comment that most children today whose parents follow the advice in your books are hardly experiencing these extreme circumstances. And you’re right. But by knowing what happens in the extreme cases, we’re able to understand some of the subtler effects that can arise from moderate use of these behaviours. It is important to remember that these effects exist on a sliding scale – it’s not all-or-none – and that regular neglect of some elements of the psychological and emotional will have long-term and far-reaching effects.

To sum it all up… despite behaviourists’ best attempt to have us belief that infants are indeed blank slates with no psychological states, we know that not to be the case. Infants may lack meta-awareness, but they feel and experience the world socially and these states are arguably as important as their physical state. Research has demonstrated that the failure to meet these psychological and emotional needs can lead to severe mental deficiencies, physical illnesses, and even death. As people offering parenting advice, instilling the notion that a baby’s needs are met because they are fed, dry, and warm is simply ludicrous and horribly damaging to these babies. So what can you promote? Well, that’s something you can read more about in the book Educating the Experts.

I can’t express how grateful I am to you for writing these posts. Now, all we need is certain people to read them!

Fantastic article, Tracy!

I would like to discuss one aspect of the whole ‘cry it out (CIO)’ sleeping training techniques out there: usually, sleep training advocates argue that letting the child to CIO to learn how to sleep by itself cannot be compared to situations of lack of a parental relationship or love. They argue that the training sections are a very small part of their lives together, just a temporary and short phase in their relationship, that is compensated by lots of cuddling during the day. And that the result of the training sections is beneficial for all of them- parents and children better rested, what allows then in turn having a better relationship after all.

What do you think about this?

While I agree the some of the sleep training methods cannot be compared to situations like child neglect, and that well rested parents tend to have more patience for the child during the day, I am strong against CIO because we cannot predict how long the crying sections are going to be, and whether it would be harmful to the parent-child relationship (detachment). And also, as we know, too much stress hormone in the developing brain is not a good thing, physiologically thinking.

As you commented in the end of the article, there are subtler effects and they exist on a sliding scale.

Andreia, I completely agree! And I hope to tackle the issue in the next “lesson” on touch. Sadly, babies don’t understand this mixed message of cuddles during the day and abandonment at night – in fact, it flies in the face of their arguments that babies prefer routines (to know what’s coming; another lesson). Teaching them to expect different parental behaviours at different times of day is just ridiculous. And then, of course, there are the neurological effects of crying (regardless of how long, it’s something that produces cortisol and should be minimized).

Daughter wants to go for a walk so I’m off, but all wonderful points 🙂 THANK YOU!

Great post! (I didn’t find it dry at all) I love the sentence about ‘you’re either a psychopath or lying’. I remember watching a documentary about orphanages in Romania right after the soviet colapse. Watching the children wuming in their cribs, some of them you could see actual caluses (sp?) On their foreheads from all the time just spent rocking back and forth into the bars or wall, was truly heartwrenching. My best friend was sitting right next to me. And we both shared a nearly in tears look when they recited some of the minor birth defects that could land a baby in such a place because the parents were too poor to afford even the most basic of care, both of us were born with easily corrected (more or less) defects that would have landed us in there if we’d been destined to be born in a soviet block country instead of America (doubly pointed because we knew someone born and raised in Poland who would not speak about his childhood to the children/young adults in the congregation because it wasn’t appropriate for young ears).

On another point I always felt it was really obvious which kids belonged with parents who were aware that infants/toddlers/young children take social ques from their parents and which belong to parents who have no idea how much they absorb their parent’s reactions. No one is this as obvious as in pain/fear response. The parents who hover terrified over their infants while the nurse readies the shots are the parents whose infants scream uncontrolably for 20 minutes afterwards. And the parents who rush with anxious faces and wails of concern everytime their toddler takes a little spill have the toddlers who wail inconsolably (sp?? at every trip and spill.

Docs and nurses always comment on how well my kids do with shots and blood draws. I refuse to make a big deal about it (and keep my husband away cuz he just can’t not get overly worried about such things!) So my kids do as well. It’s so important to model the social behavior you want your kids to pick up, because they do.

Oh and looking forward to your post on touch, as that’s a personal interest of mine.

[…] Lovely post here https://gku.flm.mybluehost.me/evolutionaryparenting.com/?p=387 […]

These posts are fabulous! Please keep them coming 🙂 In particular I have been reading the first lesson out loud to family members who are still stuck in the “old-school” way of thinking (even though they try not to be). I am thinking about sending these links on to my mother-in-law too who says I should let my son cry to “exercise his lungs”, leave him in his bassinette alone (crying) to settle himself to sleep when what he really wants is physical contact and to be rocked to sleep, and the latest is that at 4 weeks old he should now be put in his own room and cot during the night…. ugh people! I’m going to be looking through your posts for info on co-sleeping arrangements as hubby and I have been discussing the whole keeping baby in the room with us (currently he is either in his bassinette by my side of the bed, or in the bed with us if he’s having a rough night) until he is over a year old (which would probably see us move his cot into our room with us). My mother even looked a bit horrified when I mentioned doing that and brought up the whole “making a rod for your back” comment. But we’re determined to do whatever is best for our baby – I’ll be checking out your website for any info you have on these situations too 🙂 Keep up the great work – I have subscribed to your RSS feed so I’m updated whenever you post 🙂

Hi Donna, I hope the posts help! There are articles on co-sleeping and the safety of it (do’s and don’ts) as well as how it can foster independence in children. I would also check out the post on breastfeeding and co-sleeping to share with your mother 🙂 FYI, my daughter is 14 months old and still in bed with us – we plan on doing the family bed until she’s ready to move on. I can’t tell you how amazing it has been for us – I just love it (as does my hubby and daughter). You obviously need to do what works for your family, but remember your mom isn’t sleeping in your bed 😉

Fantastic reading Tracy.

Hope that more people read this article.

[…] בשביל לקרוא את המאמר המקורי, תלחצו כאן. […]

[…] attention, affection or movement. On the Evolutionary Parenting website you can read about it in Lesson two: Needs (warning: contains explicit […]

I wanted to clear up a little wording issue you have going on in your articles. You keep useing behaviourism as a word to describe one aspect of a whole. Learned helplessness is PART of behaviourism. I would hate for you and others to label and condemn behaviourism as bad or inaccurate or wrong because you wrongly labled only the early part. Please understand learned helplessness is part of behaviourism and recognized as a bad and improper use by many who love and understand operant conditioning. Those who truly understand that learned helplessness and the methods of purposefully or not obtaining it are just a fragment of the whole science called behaviourism. There is so much more to it then just the negative have pointed out. In fact many of your ideas that are positive and science proven, also fall into behaviourism as a whole. B.F. Skinner was one of the scientists to prove that positive methods were more effective Because of learned helplessness and other negative fallout of punishment. Please don’t make same mistakes as those you criticize. Don’t label one part of an entire science as bad and forget to say that the positive and good also the remedy are in essence still the same science labled. K?

You are very right that I am referring to first-wave behaviourism as opposed to behaviourism as a whole. Thank you for pointing that out!

[…] ovo nas vodi u to da će tema sljedeće lekcije biti Lesson Two: What are an infant’s “needs” (link vodi na tekst na engleskom jeziku, op. prev.) Osnovica vaših programa jest da govorite […]