Abstract: Bedsharing in Western cultures is often looked down upon and considered socially inappropriate. In the younger ages, safety fears run rampant, but even when these fears subside, bedsharing remains taboo. The largest cultural concern with bedsharing beyond infancy is that somehow it will stifle a child’s social development, particularly in the realm of independence. However, research that has examined this question finds absolutely no support for this belief; indeed, the research that has been done supports either no distinction between children who bedshared beyond infancy and those who did not on myriad outcomes or the findings support a benefit to bedsharing beyond infancy. Regardless, the notion that bedsharing will hurt or damage a child is unfounded.

***

One of the biggest responses when people hear you bedshare in our Western society is that your child will never learn independence. You will forever be tied to your child, they will refuse to sleep alone, and you’ll spend your life having to care for them. This is especially true if you bedshare beyond that young infancy period (and of course if you bedshare during infancy, you may be told you’re putting your baby’s life at risk, but despite the media grasping to articles suggesting danger, far more detailed studies suggest safe bedsharing isn’t dangerous at any age[1][2]). Should you fear that you will turn your child into a clingy, dependent child and adolescent and grown up who won’t be able to cope with the world at all? Let’s see…

Historical and Cross-Cultural Evidence

I will get to the scientific evidence, but I prefer to start looking at things historically and cross-culturally for this one. Bedsharing – and extended bedsharing – has been a staple in human history for far longer than it has been considered weird or abnormal.

The Hunter-Gatherer Story

In a wonderful review of human history and behaviours, Jared Diamond covers how prominent bedsharing was in human history, with families sleeping together in small quarters, especially with infants and young toddlers, and how it persists in small scale societies today[3]. Indeed, no tribe was found not to bedshare. Notably, when not in a culture that doesn’t support co-sleeping or bedsharing, humans follow the same trajectory as other primates in that co-sleeping (used here as bedsharing isn’t quite appropriate when speaking of apes, though perhaps nest-sharing is) is common into “toddlerhood” but is often ended or reduced shortly after weaning (for a review, see [4]).

Given our very early weaning ages in our society, it’s not too surprising we expect infants to be in their own bed, but looking at it from a historical, biological, anthropological, or evolutionary perspective, it just doesn’t make sense. When weaning is a natural process not rushed by cultural or societal expectations, the average age of human weaning ranges from 2 to 7[5]. As such, it’s really not until early childhood or adolescence that we would expect to see children move to a bed (or room) apart from their mother, and this is exactly what the research finds when we look at cultures where this initial weaning behaviour is the norm[6].

In a comparison of two small-scale, hunter-gatherer tribes—the Aka and Ngandu—it was found that there were differences in the way co-sleeping occurred[7], suggesting room for variability across cultures, but that its existence in toddlerhood was pretty much a given. Although infants and young children bedshared at near 100% rates in both tribes, by middle-age, the Ngandu children were more likely to be sleeping with siblings than their parents while the Aka children continued to bedshare with parents, even into early adolescence. Thus the moving out of the bed time does vary, but again, not until much later than our Western ideas would permit.

We must ask though: What of these children’s independence? The modern (or not-so-modern) hunter-gatherer child is raised in a very “dependent” way: Long-term breastfeeding, lots of human contact (99% of the time before they are crawling, by some estimates[8]), and yes, bedsharing. By our standards this child should be incapable of much, but by 10 years of age, these children have responsibilities and capabilities far greater than many of our own children, and in the Aka and Ngandu tribes, the children are capable of building their own homes by this age.

As Jared Diamond reports in his book, in one of his journeys through the jungle, his guide was a 10-year-old child who left his family and tribe for days to accomplish this. The child’s knowledge of his surroundings and of survival surpassed most Western adults. His independence was incredibly clear to those around him. In addition, he found the responsibility of childcare in small-scale societies often falls to girls as young as 6 years of age who help care for the younger toddlers and they are able to feed and watch over these young infants at a time when we in our Western society are arresting parents for leaving 2-year-olds alone with 8-year-olds for short times in emergencies.

The Stories of Other Cultures

Even today, when we consider other cultures, we see bedsharing remains prominent in many other cultures for extended periods. For example, Barbara Welles-Nystrom examined bedsharing habits in a Swedish sample and found that bedsharing rates actually peaked at ages 4-5, with over half of the children in the sample reportedly bedsharing at least part of the time on a regular basis[9]. I don’t know anyone who wants to suggest that Swedish culture is rife with individuals who can’t function. Indeed, they have lower rates of childhood behavioural problems than those of us in North America[10].

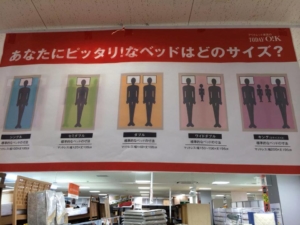

Asian cultures are known for their bedsharing habits, both in infancy and beyond. Japan is perhaps the most famous example in which traditional Japanese homes have one room for the family to sleep in—until kids leave the family house. Westernization has definitely taken over there, but they still boast some of the highest rates of bedsharing in the developed world[11]. Even buying a mattress there, you are urged to make your decision based on the number of children that will be present in your bed (see the image below). Like Sweden, it is difficult to suggest that Japanese, or any Asian culture, have adults who struggle with responsibility or are not successful because of the type of “coddling” they received in their bedsharing upbringing.

Of course, historical and cross-cultural research doesn’t say everything and arguably may not be relevant to our own culture (though I would disagree with that and remind you that even our own culture used to bedshare regularly until having extra room became a sign of status and symbol and was something to aspire to), so let’s look at the other kind of evidence: Scientific.

Scientific Evidence

What does science tell us? Well, first we have to be clear that there are less than a handful of articles that have addressed the issue of longer-term bedsharing in our culture. If I had to summarize them, I would say that, taken together, they have found that children who bedshare beyond infancy either show no differences in outcomes to those children who sleep alone or they show better outcomes. Yes, you read that right, so let’s take a look one by one.

Study #1: An 18-year Longitudinal Study

The first study, by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, are the results of an 18-year longitudinal study on parenting behaviours and child outcomes[12]. The study included 205 families from “nonconventional and conventional families” in the California area and the children were followed from birth to age 18. Bedsharing was assessed at 5 months and then at 3, 4, and 6 years of age, providing information on bedsharing in infancy and in early childhood. The rates of early childhood bedsharing were small—7% at age 3, 10% at age 4, and 4% at age 6 (slightly smaller for regular bedsharing with 6%, 6%, and 3%, respectively). Interestingly, girls were 50% more likely to bedshare than boys, raising the question of whether it is due to different sleep patterns or perceived inappropriate behaviour between a mother and son.

When looking at outcomes at age 6, earlier bedsharing was positively associated to cognitive outcomes (i.e., bedsharers showed greater cognitive competence as assessed using a battery of tests including the Weshler Intelligence Scale for Children, the Children’s Apperception Test, the Moral Judgment Test, and more). There were no differences in behavioral and emotional maturity, mood and affect, school adjustment, parental sexual concerns, or creativity based on bedsharing status (i.e., you couldn’t differentiate which child bedshared and which didn’t). At age 18, you couldn’t differentiate bedsharers from non-bedsharers on any of the outcome variables which included factors pertaining to sexuality, relationships with others, self-esteem, antisocial behaviours, and drug use. In short: Bedsharing does not lead to any negative outcomes for children. As the authors state when talking about the fears of problems in children who bedshare, “We suggest that such fears are without warrant if bedsharing is practiced safely as part of a complex of valued and related family practices.”

Study #2: A Preschool-Age Assessment of Sleeping Arrangements

This second study examined sleeping arrangements from birth to 3 years of age in a sample of preschoolers recruited from preschools (i.e., all children were regularly in preschool at the time of the assessment)[13]. Parents were asked to report on sleeping arrangements for every six-month interval starting at birth and ending at 36 months. “Early co-sleeping” families were defined as those who began co-sleeping at birth and who continued beyond 12 months of age, “solitary sleepers” were those children who were moved to their own bed before their first birthday (often around 6 months of age) and remained there, and finally “reactive co-sleepers” were children who were moved to their own room around 6 months, but were brought into a co-sleeping arrangement after 12 months of age and remained that way for at least 6 months. Other variables assessed included maternal attitudes towards sleeping arrangements, children’s independence in sleeping behaviours, self-reliance (e.g., getting dressed by oneself), and social independence (e.g., ability to make friends), maternal autonomy support (i.e., behaviours that support a child’s autonomy and encourage problem-solving, initiative, and exploration in the child), and maternal control (i.e., behaviours that pressure children to conform to the parental wish).

It is worth noting that based on common consensus, the authors assumed that solitary sleepers would show the greatest independence, so any confirmation bias would exist to support that view. The sample was well distributed amongst sleeping types, with 39% being solitary sleepers, 34% being early co-sleepers, and 28% being reactive co-sleepers. With respect to sleep independence, solitary sleepers woke significantly less than both co-sleeping groups, though only the reactive co-sleeping group found the night wakings somewhat problematic. Neither the solitary sleeping group nor the early co-sleeping group found night wakings to be a problem. There was a marginal association with bedtime struggles, but only for the reactive co-sleeping group; again, the other two groups reports no bedtime struggles. So, with respect to sleep independence, it seems that early, planned co-sleeping results in no differences or problems with sleep.

What of other independence? Well, contrary to what the authors expected, they found that it was the early co-sleepers who showed far more independent behaviours, both with respect to self-reliance and social independence. This main effect was maintained even when maternal behaviours that supported autonomy were controlled for. This was important as mothers of early co-sleepers were significantly more supportive of their child’s autonomy than the mothers of solitary sleepers or reactive co-sleepers. It seems contrary to public opinion, co-sleeping not only was not detrimental to children’s independence and autonomy, but when done early and intentionally it was associated with greater independence and autonomy in the preschool years.

Study #3: Long-Term Low-Income Group Analyses of Mother-Child Bedsharing

The third study comes to us from New York (jointly between Columbia University and the State University of New York at Stony Brook) and looks specifically at low-income families[14]. The sample was taken from the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Study which only includes families at or below the poverty line, and a total of 944 families were included in the analyses (note that not all are part of the EHS program, only half of eligible participants are assigned to Head Start). Bedsharing was assessed at ages 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years while cognitive and behavioural outcomes were assessed at 5 years of age. Bedsharing was divided into those that reported never for all three times, reported yes for 1 time frame, and then yes for 2 or more times. In addition, parenting variables were assessed as were maternal depression, poverty status, and adult male in the house.

In this sample, both Hispanics and Blacks were more likely to bedshare than non-Hispanic Whites, either at 1 time point or ≥ 2 time points. Interestingly, negative regard for the child predicted bedsharing at 1 time point, but not ≥ 2 time points; indeed, no maternal variable predicted bedsharing ≥ 2 time points (this may reflect the type of “reactive bedsharing” highlighted in Study #2). With respect to outcomes, contrary to Study #2 above, children who bedshared ≥ 2 time points were rated as showing lower social skills at age 5 (though the mean differences were very small and thus statistical significance could be due to the large sample; M=11.68 vs. 12.10). Furthermore, children who bedshared at ≥ 2 time points also showed lower cognitive scores for both verbal skills and problem solving.

This would suggest that there are problems with extended bedsharing for these low risk families, right? Not quite. As soon as the authors conducted analyses controlling for other variables to determine if it was bedsharing per se that caused the problems (and not other factors like SES or other maternal characteristics), all of the associations disappeared. With respect to social skills, as soon as child characteristics (i.e., child sex, low birth weight, and in EHS or not), mother’s place of birth, and ethnicity were included, bedsharing lost significance. With respect to verbal skills, the addition of child characteristics, mother’s place of birth, ethnicity, SES characteristics, maternal education, mothering behaviours, and mother’s depression reduced bedsharing to non-significant status. Finally, with respect to problem solving, the addition of child characteristics, mother’s place of birth, ethnicity, SES characteristics, and maternal education nullified the significance of bedsharing. The relationship to bedsharing was deemed a third-variable issue in that it was related to many of these characteristics and thus seemed significant, when indeed the other better explained the outcomes.

Conclusions

Bedsharing beyond infancy is not abnormal in human culture, even our own Western one (see Table 3a in [7] for evidence of its commonness). People seem to fear the independence bit yet there is not a shred of evidence to support such a view. In fact, it seems bedsharing beyond infancy is biologically and anthropologically normal and as such, has zero negative effects for children (or families) cross-culturally. Though some families continue bedsharing into adolescence, it is not incestual (indeed, sexually mature children only bedshare with same-sex parents in tribal communities [7]) and still remains rare. The biological expectation is that children will cosleep at least until they are weaned at the biologically normative age, then slowly transition to sleep away from parents (which may still involve cosleeping with other siblings), and most are doing so by adolescence.

Bedsharing or cosleeping beyond infancy may not be for you—and there’s no problem with that—but to fear or suggest that a child will be damaged by the practice in any way simply holds no water whatsoever. As such, the decision to extend the family bed beyond infancy is a personal decision based on individual values, culture, breastfeeding, and what works for the family. It’s time we stop the ridiculous, evidence-lacking fear-mongering for good and let families sleep how they may.

_______________

[1] Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Pease A, Fleming PJ. Bed-sharing in the absence of hazardous circumstances: Is there a risk of sudden infant death syndrome? An analysis from two case-control studies conducted in the UK. PLOS One 2014; 9: e107799. [2] Blabey MH, Gessner BD. Infant bed-sharing practices and associated risk factors among births and infant deaths in Alaska. Public Health Reports 2009; 124: 527-34. [3] Diamond J. The World Until Yesterday. New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2012. [4] Watts DP, Pusey AE. Behavior of juvenile and adolescent great apes. In ME Pereira & LA Fairbanks Juvenile Primates: Life History, Development, and Behaviour. Oxford University Press, 1993. [5] Dettwyler K. A natural age of weaning. http://www.kathydettwyler.org/commentaries/weaning.html [6] Yang CK, Han HM. Cosleeping in young Korean children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 2002; 23: 151-7. [7] Hewlett BS, Roulette JW. Cosleeping beyond infancy: culture, ecology, and evolutionary biology of bedsharing among Aka foragers and Ngandu farmers of Central Africa. In D Narvaez, K Valentino, A Fuentes, J McKenna, & P Gray’s Ancestral Landscapes in Human Evolution: Culture, Childrearing and Social Wellbeing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. [8] Hewlett BS. Diverse contexts of human infancy. New York: Prentice Hall, 1996. [9] Welles-Nystrom B. Co-sleeping as a window into Swedish culture: Considerations of gender and health care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science 2005; 19: 354-60. [10] Larsson B, Frisk M. Social competence and emotional/behavior problems in 6-16 year-old Swedish school children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999; 8: 24-33. [11] Mindell JA, Sadeh A, Wiegand B, How TH, Goh DYT. Cross-cultural differences in infant and toddler sleep. Sleep Medicine 2010; 11: 274-80. [12] Okami P, Weisner T, Olmstead R. Outcome correlates of parent-child bedsharing: an eighteen-year longitudinal study. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 2002; 23: 244-53. [13] Keller MA, Goldberg WA. Co-sleeping: help or hindrance for young children’s independence? Infant and Child Development 2004; 13: 369-88. [14] Barajas RG, Martin A, Brooks-Gunn J, Hale L. Mother-child bed-sharing in toddlerhood and cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Pediatrics 2011; 128: e339-47.

Super article! I’d read similar somewhere that the great apes transition their young from sleeping with Mum by having older offspring sleep next to Dad or other family member instead so they develop independence gradually and confidently. Makes total sense. Our 3.5 year old starts the night in his own room but we usually find him in bed with us by the morning (he’s 2.5). Bed shared til he was 18 months so this is a nice half way house.

I believe that there is a possibility that bedsharing could also lead to longer-lasting relationships.

I have no current evidence to back up this theory, but it would be interesting if there is any way that it could be proven.

I feel like we, as humans, are co-dependent, and not allowing children to share a bed could harm their development, including the relationships that they could have in their future.

I also believe that bedsharing helps to show a need to share, in general, which is very important and not something that many younger parents are teaching their children, nowadays.

That’s my opinion, anyways.

This article is perfectly timed for my situation! My son is 13 months old and we’ve co-slept with him from the very beginning. I got the typical “you’re putting your child at risk” lecture from his pediatrician, and from other people in my life I got the “you’re creating a bad habit” type remarks. All I had to do was tell them that he’s been sleeping through the night since he was three months old, and that usually would quiet the naysayers. However, now that we’re past the infant stage, the negative comments are becoming more abundant, and it’s hard not to question yourself as a mother. Or at least I find it to be so. Bedsharing feels right, my husband and I both enjoy having our son in bed with us, and it makes perfect sense when you look at it from a biological viewpoint. It’s well written articles like this one that help give me the confidence to move past the doubt and continue to do what I feel is right for our family. Thank you, Tracy!

Our eldest (now 9yo) decided at 5 years + 2 weeks that she was ready for her own bed. No stress, no fuss.

Our second child is 3 months old & I love cosleeping with her. She’s welcome in our bed for as long as she’d like to stay 🙂

Going off on rather a tangent (I completely agree with the main point of your post), I was struck by the sentence ‘When weaning is a natural process not rushed by cultural or societal expectations, the average age of human weaning ranges from 2 to 7’. That strikes me as pretty misleading.

Firstly, of course, the paper you’re citing there isn’t a study of what *is* happening, but a thought experiment drawing analogies with animal development and looking at what our weaning ages *would be* if we weaned at various stages analogous in various ways to those at which animals wean. So it’s not really correct to say that the average age of human weaning *does* range from 2 to 7 – there are certainly many societies in which it’s 2 or more, but I’ve never heard of a single one in which it was 7. (There are individuals who’ve been reported as nursing for that long or longer, but I’ve yet to hear of a society in which that was the average.)

Also… it seems contradictory to me to talk about weaning sometimes being ‘a natural process not rushed by cultural or societal expectations’, because, of course, the natural thing in human societies *is* to have cultural/societal expectations about when children should wean. The most common one, from all the reading I’ve done, seems to be related to the next pregnancy – children are typically either expected to wean when the mother becomes pregnant with the next baby, or when she thinks it’s time to do so. I think it’s misleading to talk about natural processes here as though they were something that could be divorced from life’s demands and expectations, which are just as natural in their own way.

Weaning could relate to emotions as well, don’t be so literal … Personally, I think the article is well-grounded and to me it makes perfect sense. I followed the social and cultural ‘expectations” with my first child for her first three months and I still feel sorry for that. I co-slept will all my children ( with the first one till the age of 7 when she decided that it’s “too hot in the summer to sleep with Mum & Dad” ) at one time there were 4 of us in the bed ( and me being pregnant) And guess what ? None of my children is any closer to emotional/ physical or any other kind of dependence. We are parents 24/7 no matter of what and children should know we are there for them anytime, even if they want to touch our ear all night long … for the first 2-7 years of their lives 🙂 Is it comfortable for me? Not always, but I should’ve thought about that before having kids 🙂 After all we are adults and we are supposed to know the difference between “dependence” and “support” , aren’t we?

[…] To be honest, it was a challenge for me to start as we have it ingrained in us that we HAVE to sleep by our partner (why?), baby MUST have their own bed and own room (this is a recent thing; I have heard that the aristocracy would show their wealth by having baby in another room to show how wealthy they were (lah di dah we can afford another room!), the lower classes soon followed suit once lifestyle and income allowed) when science suggests we are designed to sleep by our little ones (I also love this article; bed sharing with an older “baby” is not harmful and how is it your business anyway!?) https://gku.flm.mybluehost.me/evolutionaryparenting.com/bedsharing-beyond-infancy-the-question-of-independence/) […]

Adults don’t like to sleep alone, why should children? My 2 co-slept with us until they were ready to leave and they are happy, well-adjusted, intelligent and secure.

[…] • Articles- https://gku.flm.mybluehost.me/evolutionaryparenting.com/bedsharing-beyond-infancy-the-question-of-independence/ […]

Hi Tracy.

This artical is a great examination of the effect on the child.

I am a 42 yo stay at home dad who has been displaced at night due to the many negatives of co sleeping with our 2 yo. Lack of room, contant awakenings, the 60 minutes it takes everynight from 1 of us to put her to sleep.

Your artical was sent to me by my wife to support her claim for continuing Co sleeping. I just wish it had said somewhere in there about the strain it can have on a marriage just because my wife is “not ready to give it up yet”.

I would say what you’re describing is indicative of something else going on with sleep given how long it takes to go down. I wouldn’t be blaming co-sleeping as it may not be a panacea for this, but actually make things harder if your child was in another room. But looking into other causes is important.

But also, this article was just on that one element – too much to discuss ALL elements in one piece 🙂