The issue of daycare is probably the only other topic to rival infant feeding as one of the most contentious in parenting discourse today. The idea that daycare may be “bad” for a child has many parents seeing red, despite much research that decries the quantity and, most importantly, the quality of daycare being used in many (but not all) developed nations today (e.g., [1][2][3][4][5]). One of the means we have to look at how children are adapting to daycare is to examine their cortisol levels during the transition to daycare, after the transition, and at home. Cortisol can tell us about the degree of stress that is caused by the separation to the primary caregiver and for how long this type of stress continues.

What we seem to know so far is the following (with a caveat that although there is a fair bit of research that converges in this area, it is far from conclusive due in part to the many variations of care that exist):

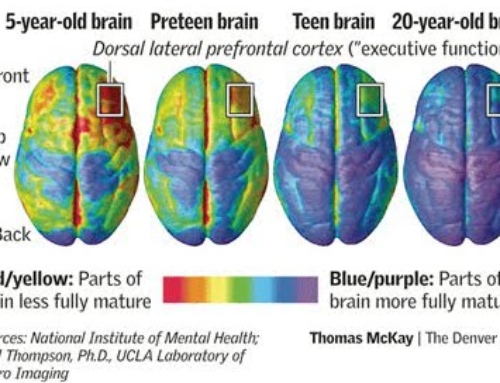

- Cortisol has been consistently found to increase over the course of the day in daycare (versus when a child is at home with a primary caregiver) (e.g., [6][7]) which raises a flag as to the effects on the developing brain (for a discussion of hyporesponsivity and why this increase matters, see here). Of note here is that the normal diurnal pattern is for cortisol to be highest in the morning and to gradually decrease as the day progresses so it is not just that this is muted in daycare, but we are often seeing the total opposite.

- The rises in cortisol that have been shown to exist have been found to be at least partially dependent upon the quality of care provided. Specifically, the magnitude of increase is much higher in lower-quality daycare settings[8][9] and high-quality, home-based child care seems to be associated with little to no increase in cortisol levels[10]. This provides some evidence that the rises seen are indeed reflective of stress in the daycare environment and fit with the behavioural research cited above that shows significant differences in externalizing problems based on quality of care.

- These rises are not necessarily temporary. In one study looking at young toddlers transition to daycare at 15 months, the increase that occurred during transition was still visible 15 months later[7]. This shouldn’t be too surprising as other research has not specifically looked at transition, but rather the cortisol levels of children who have been in daycare for a spell already.

- Child temperament influences the degree of increase in cortisol with higher needs children showing greater increases even in higher quality daycare settings[10]. This is likely not too surprising given what we know of the need for what some researchers have called “optimum” care for these children (with “optimum” meaning very attachment-based parenting) (see here for a brief discussion).

- Age influences this cortical effect, with younger children (3 and under) showing greater effects than older children[6][11], though what remains unclear is if this is due to developmental differences or the amount of time spend in daycare. That is, do older children show this effect because they are used to daycare already or is there something that occurs during development that leads to this change.

Enter some new research aimed at examining cortisol effects during a 10-week transition to a new daycare setting across a variety of ages to see if differences in cortisol levels in daycare by age previously have been due to development of the child or the time spent in daycare[12]. A total of 168 children in the United States aged 1.2 months to 8 years of age were included with a mean of 3.27 years of age, though 34 children were over age 5 and thus in school for part of the time and thus secondary analyses were done with these children removed. Quality of daycare was not assessed, though the daycare was a center (which is often associated with lower-quality care), but was a university-based daycare (which may result in higher-quality care). Cortisol samples were collected six days over the study time period of 10 weeks (day 1, weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10), twice per day (morning and afternoon) and were collected during times that activities would not influence levels (e.g., eating or sleeping or playing outside). For 129 children, parents collected saliva samples at home for 2 consecutive days prior to them entering the daycare. Not surprisingly, there were many missing data points for cortisol levels given that a child who was away on any of the six time periods would have missing data; however, missing data analysis revealed no associations of missing data with most key variables with the exception of minority status in which the home morning sample was more likely to be missing (age was also a factor in that older children were more likely to be missing the center morning value but this is not surprising as older children were in school and thus not at the center for morning collection).

There were some nuances though that are worth looking into. In terms of the increase in change over time, this was not driven by a small group of children, but rather a higher percentage of children showed an increase in cortisol throughout the day as the weeks went by as opposed to some form of attenuation. For example, in the infancy group, 39% showed a rise on day 1, 30% on the week 2 measurement, 38% on week 4, 54% on week 6, 60% on week 7, and 47% on week 8. Though this may seem sporadic, there is a significant general linear trend and this is mirrored in all three age groups.

The question of interest, however, was how age influenced findings. In this regard, there was a quadratic effect of age with the greatest increase in cortisol occurring in the preschool years (over infancy or school-age years). There were also differences in the types of effects. At home in infancy, the “normal” pattern was virtually no change in cortisol from mid-morning to afternoon (not surprising given that this diurnal pattern of a decline can take months to even remotely establish and further develops for years) whereas in daycare there was an increase from mid-morning to afternoon. At home in the preschool years, there was a moderate decline from mid-morning to afternoon, but at daycare there was an increase (i.e., there were totally opposite patterns). In school-age children, at home there was a steep decline from mid-morning to afternoon, but a relatively stable level in daycare. Thus the daycare effect was similar for infants and toddlers, though the home effect differed, but the daycare effect differed for older children.

There are a few considerations that deserve discussion based on the pattern of findings. First, it is worth noting that the failure to show home-like patterns at the end of 10 weeks does not support the idea that children fully adapt to the daycare environment. Rather, there are continued struggles relative to a home environment.

Second, this finding of a failure to adapt coupled with the largest increase being in the preschool years suggests a large portion of this may be driven by peer interactions. That is, toddlers and preschoolers are the group most likely to struggle with peer interactions and what is expected of them in this regard in a daycare environment (think sharing), causing the most difficulties over this time period (and based on other research, continuing for months[7]). Infants don’t really engage with peers and school-age children have had far more experience in this realm and know what is expected of them, although infants do show the same rise in cortisol, suggesting they also experience stress, it is just not as magnified as with the toddler group.

Third, how should we interpret the drop in mid-morning cortisol levels? There are three possibilities raised by the researchers:

- The results may suggest there may be some adaptation to the parental separation. The results found that there were decreases to the mid-morning levels of cortisol which could suggest that the early weeks were representative of stress upon leaving the parent which does seem to attenuate as the weeks progress.

- In line with other research[11][13], is that children (even infants) “anticipate” daycare days and have higher HPA axis activity overnight, resulting in periods of hypoactivation the following morning. This means that the anticipation of daycare causes stress and by the next morning, their brains have gone into a period of hypoactivation to compensate for the higher levels of adrenocortical activity overnight. (Total aside: What’s interesting about this is that this idea of cortical “anticipation” might negate one of the criticisms of the research looking at cortisol levels during extinction sleep training[14]. Namely, the infant in that study showed high levels of cortisol just prior to the onset of the bedtime ritual on all days tested, even though mom was present with the child, and many speculated that this stress was due to the new environment, despite most research suggesting new environments with mom don’t result in this change. My speculation had been the anticipatory nature of bedtime that had been problematic for the families leading them to the sleep clinic in the first place. Anyway, just thought I’d share that tidbit here though it has no bearing on daycare.)

- The third possibility is that the sleep changes that often go along with transitions to daycares result in a shifting of the cortisol levels at the midmorning assessment if they have been waking earlier the longer they are in daycare. This presupposes that the patterns of sleep-wake times shifted significantly over the 10 weeks, something that was not measured in this particular study, but remains a possibility.

Most importantly, how does this fit with other research on daycare? It seems to fit quite nicely in with what we already know: Namely, that daycare results in changes to cortisol levels, specifically changes in line with possible stress responses. This adds to the body of research by demonstrating that these changes occur during transition regardless of age, though the magnitude and effect differ by age. Perhaps most importantly, this study failed to assess quality of care which raises questions about the applicability to all daycares.

This is critical as other new research on daycare that was published recently was used to debunk the idea of any long-term externalizing problems[15]. However, this research is difficult to extrapolate or compare to the bulk of behavioural research cited earlier for one big reason: The daycare in question was in Norway, not the United States where the bulk of the behavioural research has been done. Scandinavian countries are renowned for having excellent, high-quality daycare for all children, something that is lacking in the USA and elsewhere. In line with this, many of the effects seen in daycare are eliminated or at least minimized when the daycare is deemed “high-quality” (and why I believe we need to push for high-quality daycare on a larger scale for families who need it), as mentioned previously. This is important if we view the cortisol levels as being a flag for possible stress that would impact long-term development, particularly social development if the stress is, indeed, peer-related.

Interestingly, even in the Norwegian study, there were differences in levels of aggression based on time spent in daycare at 2 years of age, but rather these effects had faded by 4 years of age. This could suggest that daycare is stressful for children, but that higher-quality daycare helps children adapt and cope with this stress in a manner that is conducive to longer-term well-being. In lower-quality care, the stress is left to build up with little support from caregivers, leading to a higher risk of longer-term problems based on time spent in this lower-quality care and child temperament.

As I nearly always write when it comes to daycare, the take-home message here is that we need to fight for high-quality care and for families to have the options of staying home during these critical developmental windows. Though I acknowledge not all families will want to or be able to take advantage of being at home, it should be an option for all. (This is particularly important for parents of higher-needs children who seem to be most affected by their environment.) For those that utilize daycare, being able to find and use high-quality daycare is essential for the well-being of our children.

_____________________________

[1] Loeb S, Bridges M, Bassoka D, Fuller B, Rumberger RW. How much is too much? The influence of preschhol centers on children’s social and cognitive development. Economics of Education Review 2007; 26: 52-66. [2] Magnuson K, Meyers M, Ruhm C, Waldfogel J. Inequality in preschool education and school readiness. American Educational Research Journal 2004; 41: 115-157. [3] Vandell DL, Belsky J, Burchinal M, Steinberg L, Vandergrift N, NICHD ECCRN. Do effects of early child care extend to age 15 years? Results from the NICHD study of early child care and youth development. Child Development 2010; 81: 737-756. [4] Belsky J, Vandell DL, Burchinal M, Clarke-Stewart KA, McCartney K, Owen MT, NICHD ECCRN. Are there long-term effects of early child care? Child Development 2007; 78: 681-701. [5] Pluess M, Belskey J. Differential susceptibility to rearing experience: the case of childcare. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2009; 50: 396-404. [6] Dettling AC, Gunnar MR, Donzella B. Cortisol levels of young children in full-day childcare centers: relations with age and temperament. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1999; 24: 519-36. [7] Ahnert L, Gunnar MR, Lamb ME, Barthel M. Transition to child care: Associations with infant-mother attachment, infant negative emotion, and cortisol elevations. Child Development 2004; 75: 639-50. [8] Legendre A. Environmental features influencing toddlers’ bioemotional reactions in day care centers. Environment and Behavior 2003; 35: 523-49. [9] Lisonbee JA, Mize J, Payne AL, Granger DA. Children’s cortisol and the quality of the teacher-child relationships in child care. Child Development 2008; 79: 1818-32. [10] Dettling AC, Parker SW, Lane S, Sebanc A, Gunnar MR. Quality of care and temperament determine changes in cortisol concentrations over the day for young children in childcare. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2000; 25: 819-36. [11] Ouellet-Morin L, Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Meaney M, Kramer M, Cote SM. Diurnal cortisol secretion at home and in child care: A prospective study of 2-year-old toddlers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2010; 51: 295-303. [12] Bernard K, Peloso E, Laurenceau JP, Zhang Z, Dozier M. Examining change in cortisol patterns during the 10-week transition to a new child-care setting. Child Development 2015; 86: 456-71. [13] Gunnar MR, Tout K, de Haan M, Pierce S, Stansbury K. Temperament, social competence, and adrenocortical activity in preschoolers. Developmental Psychobiology 1997; 31: 65-85. [14] Middlemiss W, Granger DA, Goldberg WA, Nathans L. Asynchrony of mother-child hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity following extinction of infant crying responses induced during the transition to sleep. Early Human Development 2012; 88: 227-32. [15] Dearing E, Zachrisson HD, Naerde A. Age of entry into early childhood education and care as a predictor of aggression: faint and fading associations for young Norwegian children. Psychological Science 2015; DOI: 10.1177/0956797615595011.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Very interesting. I’m curious if there’s been any research attempting to disambiguate the social context of day-care versus being separated from parents? I’m sure I have a higher level of cortisol in a group just because I find people stressful. Perhaps comparing daycare to things like cafe play-rooms or mother/parent group meetings, where the children play with (or, for infants, are exposed to) larger numbers of children but a parent is still present.

I had heard this before. It is very interesting and the permanent effects are worrying. Would be interesting to extend the study to track as you say parents and kids attending toddler group together etc. And just to increase the numbers involved and use different types of nurseries.

I wonder that you mention the children selected had maybe already had sleeping difficulties ? That might mean it is not an entirely representative group.

With regards to ref 15 – the Norwegian Study. It studied aggressive behaviour and seemed to find daycare did not affect it …..but it does not mention Cortisol …. so really it is not that relevant anyway ! Perhaps for example the children in Norway example are just so over-disciplined they sort of give up and also are not aggressive…. or they might in theory be sitting terrified with high cortisol but no aggression. I mean really you can’t compare the two studies ! And also the children in Norway for example imagine if they were in fact Unattached to their parents ? Again that might show up as low Cortisol as in fact they dont care who is caring for them …but that is not necessarily good as for people to form good relationships they need strong attachment and bonding in the first place to their primary caregiver(s) ie Mum and Dad ideally !

What the results found in the Norwegian study (when you read the whole thing) is that there WERE effects at age 2, but they had disappeared by age 4. However, it is still relevant as the externalizing (and internalizing, as found in other studies) behaviours we see may stem from the repeated stress which would be indicated by cortisol levels. So although you can’t “compare” two studies, you can definitely look at the results together to try and create a bigger picture and see where the research should go next 🙂

[…] Bron: Daycare and Cortisol Levels: What Does This Tell Us? | Evolutionary Parenting | Where History And Sc… […]

I share your concern for the results of this study, and the need for very high quality daycare for all children, but I’m not sure about extrapolating that the rise in stress levels is due to separation from parents. Daycares, no matter the quality, can have elevated noise levels, and have a larger number of people present demanding interaction and response. Just being in a daycare room with limited space because of the number of people sharing the space and the amount of noise can contribute to stress. I think daycares need to change their standards to provide more quiet spaces especially for introverted children, and to have more varied space that allows the child to change modes over the course of the day, rather than always being in the middle of an active space. Studies also find that children in noisy, disorganized schools also have elevated stress levels. To me it seems an equally logical conclusion that the daycare environment is contributing to stress levels, and studying how to improve that environment would be a valuable approach. I would add that I was a SAHM so none of my children were ever in daycare. But when I visit my grandchildren’s daycares, I notice how stressful being in that noisy space feels to me, and I wonder about how that affects them all day long.

The one thing about the parental separation is that there is research showing that during a parent week in transition (i.e., parents are allowed to stay with the kids), we don’t see the same cortisol effects. It seems to happen when parents aren’t there. However, that said, it absolutely may be part of the environment causing stress and without the buffer of an attachment figure, it becomes difficult for the child to regulate.

Notice high quality home child care had similar results as parent staying home.

Too bad the Ontario Liberal Gov and the Federal NDP can’t wrap heads around supporting ICPS in an affordable licensing system. Too Bad. HIGH QUALITY home childcare providers are having to close their businesses on a daily basis thanks to lack of gov support in bill 10.

Please join CICPO and help make changes to policies that kill home childcare.

This must be the single issue more contentious than breastmilk vs formula. In fact I’m going to admit to being too much of a sissy to write about it on my blog for fear of the backlash (every mum I know uses daycare in some form) and even considered commenting here anonymously. Daycare is ubiquitous these days, even for families who don’t need it to ensure they can buy basic amenities – I get that many mothers feel they can parent better after a break from their child, but this research clearly shows that we’re not discussing the effects on the children.

As others have mentioned I wonder what the difference is between parental separation, peer interaction, and possibly a forced scheduling. What are the coritsol levels like for children in a tribal setting or a kibbutz where they are raised by a village and not just a single parental pair? I know they show different patterns of attachment.

How do they determine the cortisol levels? If a child is poked with a needle everyday to determine levels I don’t think any such study can be accurate.

Cortisol is routinely tested using saliva samples. That’s the most common way to test it.

[…] What are our babies feeling when parents drop them at daycare or leave them with a paid parent substitute to suckle plastic nipples at 4, 8, 12 weeks old? Does their world feel good, safe, and abundant? The cortisol levels of infants separated early from parents suggest otherwise. […]

I wonder how daycare compares to situations like preschool and school. Do children of 4 and up not feel stress in the same way? My son is nearly 4 and has started attending a preschool a couple of afternoons a week. He appears to love it but his sleep has become very disturbed since he started and he spends about half the night searching for me, despite the fact that I’m right next to him. His preschool afternoons are spent mostly outdoors in a forest/farm setting with mostly free play, so if anything his sleep should be great. He’s also started asking for milkies throughout the day and night despite only having a feed before sleep and first thing in the morning for well over a year now. He runs right in to school when we arrive, waves me off with barely a backwards glance and needs to be promised that he’ll be brought back before he’ll even consider leaving. I think the childcare he’s receiving their could only be described as high quality, but it’s obviously a change in his life that’s causing him a degree of stress even though he appears extremely happy and confident while there.

This particular research included older than 4 and found cortisol differences so definitely there’s an impact. I think the question is how a child is able to cope with it. When older, the child can seek out and often gets the type of assistance needed to incorporate the change into something healthy. That’s likely harder for younger children. Of course, I’m sure it can be done for younger kids too with the right parents 🙂

[…] scientifique, on appelle le besoin de rester près de nous le lien d’attachement. En évidence, on trouve plus de cortisol, une hormone reliée au stress, dans la salive d’enfants gardés. En langage ben commun, on appelle ça Le Gros Bon […]

Im no believer in ‘evolution’ or ‘adaptation’ the way you use it. But I know what is natural and unnatural. AKA what we were created for and how we were created to behave and raise our children, but I’m not here to debate evolution vs. creation.

Its natural for babies and toddlers to stay with mom full time. Its unnatural for mothers to leave their children with strangers and numerous other babies/toddlers all day. This is why they are stressed!

Co-sleeping is also natural. Babies are more stressed when they sleep far away form mother at night. Do you think in a tribal setting or in the forest mothers left their babies for periods of time? or slept far away from them? or fed them formula? Once we get back to what is natural, how babies were meant to be raised, they will turn into happier more well adjusted children and later, adults.

[…] scientifique, on appelle le besoin de rester près de nous le lien d’attachement. En évidence, on trouve plus de cortisol, une hormone reliée au stress, dans la salive d’enfants gardés. À travers les cultures étudiées dans leur état naturel, les enfants passent en moyenne à 8 […]

I guess it’s somewhat heartening that a substantial proportion of children in Bernard et al.’s study nonetheless failed to display elevated cortisol levels in the afternoons. Assuming those percentages represent the same group of children across timepoints, I’m curious to know what it is about those children that seemed to buffer a rise in cortisol. The study did not seem to acknowledge this at all.

They didn’t seem able to assess that, but it’s a critical question. There are definitely other factors at play and some would suggest secure attachment, temperament, etc. are all possibilities. However, hopefully we don’t need much more to argue for high-quality care for all, right?? 🙂

Is there any data on which dose makes the poison? My daughter is at daycare four mornings a week starting from 23 months to now one day and three mornings.

The daycare is for children aged 2-4, there are 16 children with 2 childcarer in the morning and it’s 1:8 in the afternoon.

It’s spacious, the care is very respectful and loving and there are children in the group the new before. She was able to speak full sentences when she started. I still breastfeed.

I know it’s stress, she’s sensitive, but I use to think she can manage because of how I take care of her the rest of the time.

She hates going there, but always tells me she enjoyed when I pick her up.

Will there be lastig damage?

[…] was a study I came across before similar to this, which says:Cortisol has been consistently found to increase over the course of the day in daycare (versus when …15 months later.The article talks about measuring cortisol levels of infants and preschoolers, and […]

[…] den stressande vistelsen i stora grupper faktiskt ger permanenta hjärn -och anknytningsskador. En studie visar att 15 månaders bebisars ökade kortisolnivåer fortfarande var synliga 15 månader […]