The idea that using extinction sleep training methods will teach your child to self-soothe is a statement that is treated as truth in our society. Is it true? Not in the slightest. It may get your child to fall asleep without signalling to you, but self-soothing it is not. The main problem with the common rhetoric on extinction sleep training (outside of the glaring one in which parents are told if they don’t use it, they’re setting their child up for a life of failure and they are “martyrs” as parents) is that it ignores very real and important individual differences in both the development of emotion regulation (of which self-soothing is a component) and the degree of distress experienced by children as they are separated from their caregiver.

All humans (children and adults) struggle with emotion regulation if distress is too high. Children, especially infants, have the added problems that they haven’t had the experiences we have, their bodies don’t physiologically regulate as ours do, and they don’t have the self-soothing skills that we have learned over years of practice. In short, there is more that causes distress to our infants (especially as everything is new) and they have less capacity to deal with it. When it comes to nighttime, how our children cope and the degree to which they experience distress will be highly variable, resulting in changes and differences in self-settling.

One way to think of this is that for every level of emotion regulation, there is an associated distress level at which point these abilities cannot be implemented.

So for any given child, whether or not they are able to self-soothe will be dependent upon (1) their self-soothing abilities at that point and (2) how distressing the event is for them. I want to talk about both of these to further understand the myth of teaching a child to self-soothe using extinction sleep training.

The Development and Prevalence of Self-Soothing in Infancy

Contrary to what some believe, infants can actually show elements of emotion regulation, like arching away from a negative stimulus or looking to the source of discomfort, but (a) there is a distinction between emotion regulation in terms of avoidance versus self-soothing (remember I said self-soothing is only a component of emotion regulation?) and (b) much of the research isn’t clear that these are effortful self-soothing activities versus behaviours that are in direct response to the stimuli or situation. Although some infants show clear signs of being able to demonstrate early self-soothing techniques (like sucking on their own hand to calm down), many don’t, and none of them use these behaviours exclusively.

The most common form of “self-soothing” in infancy is to seek out a caregiver, for the act of searching for help is a form of emotion regulation (really!). After all, us adults when we are overwhelmed also seek comfort in other individuals. Importantly, even in the infants that utilize other forms of self-soothing, none of them use it exclusively. All of them also use coregulation, and use it far more frequently than any type of self-soothing.

Interestingly, few studies have actually looked at the natural developmental trajectory of emotion regulation in infancy. However, there are, luckily for us, some exceptions to this. First, a study examining emotion regulation in 3- to 13.5-month old infants found that outside of trying to move away from a negative stimulus, the most common form (and often the first sign) of intentional emotion regulation in these infants was to seek out their caregiver (in the case of this study, mothers) to help buffer their negative emotionality.

In another study, researchers examined emotion regulation in 5- and 10-month old infants and found that only 15% of 5-month-olds and 22% of 10-month-olds engaged in “self-calming” behaviour when faced with an unpleasant situation (in this case, having their arms held down in a high chair by an experimenter). The degree to which children displayed these emotion regulatory behaviours was not predicted by either child temperament (maternal rating) or maternal sensitivity or intrusiveness (gauged in a free-play interaction). At 10 months of age, far later than most sleep training begins, only 22% of infants were able to engage in “self-calming” behaviours when distressed. (Note that far more were able to engage in avoidance behaviours like trying to arch away, and more were also able to engage in social referencing for help, but neither of these qualify as the type of self-soothing that is advocated for in sleep training.)

In these studies, however, the mother acts as a source of comfort and the distress is caused by a researcher, not the parent. In sleep training, the parent is the source of the distress by removing themselves and refusing to provide the comfort or regulation the child desires (and as we have seen, the use of coregulation is the go-to for more infants). How does this affect things? We don’t know, but as stated in a piece about a group of neuroscientists working to change the way we think about brain development (and who are against the cry-it-out and controlled crying methods of sleep training):

“And questions like who was involved in the event may have more significance than simply the presence of the hormone alone because it indicates which parts of the brain will be involved in processing the stress. In the case of children, the stress initiated by a caregiver may be more significant in terms of brain neuroscience than the stress associated with, say, little Timmy’s school-yard friend Ginny, who knocks him off the swing set from time to time. That stress may cause the boy some difficulty, but the stress associated with an attachment figure leaving him at night to cry alone in his crib may be more significant.

The child’s brain can only process that as an abandonment—it has no other way to make sense of it—and while the results of that abandonment vary considerably in any given household and certainly don’t sentence the child to a lifetime of despondency—or, worse, mediocrity—the child’s brain experiences a lesson it simply cannot order or regulate except by associating care with something other than the parent.” (Source)

Although the author here states that the child’s brain has to associate care with something other than the parent, I would argue the bigger issue is that the brain associates the parent with something other than just care. Given the role of coregulation in emotional development, I don’t quite know how this can be justified, even if the effects vary widely between individuals due to other circumstances.

In line with this, there is research looking at 6-month-old’s use of self-comforting behaviours in response to several scenarios involving frustration led by their parent. As we saw in the aforementioned research, at 5-months of age, when a researcher causes distress, 15% of infants were able to use self-calming behaviours. When frustrations were parent-led (e.g., removal of toys or arm restraint by a parent), the attempt of self-comforting behaviours was found in 16% of infants, but they were barely used, with their presence noted for an average of 2% of the time the infants were distressed. As said by the researchers, “[W]ith few infants displaying the behavior for a short amount of time and most infants not displaying the behaviour.” (p.185)

What can we conclude? Though some infants are able to show some self-soothing behaviours, they are not regularly used, even (or especially?) when a parent is the source of distress. Nothing in the literature suggests that infants can be forced to adopt emotion regulation without it being learned over time and in fact, the main form of regulation for infants is coregulation, which is impossible for the child to attain when extinction sleep training is used.

The Role of Distress

The second element to be discussed is the role of distress. Even for infants who are older and may have some self-soothing skills, the question that remains is how the role of distress influences their ability to use these skills. There is a bizarre assumption in the sleep training world that all children will experience being alone in a crib the same way (because extinction sleep training is inherently for those who have their children in another sleeping environment; it’s difficult to do CIO when you’re right there, next to your baby, as in a co-sleeping relationship). That having the door shut is the same to all and that if one child wimpers for 2 minutes, it must mean it isn’t distressing for anyone. The kids that cry more aren’t truly distressed, just “protesting”.

The problem is that we know there are huge individual differences in the expression and experience of distress. Much of the research on the development of emotion regulation highlighted above has found as much. For example, in the study looking at parental frustration for the infant, researchers were able to categorize infants by the degree of frustration they experienced, with some being easily frustrated and others being significantly less so. Furthermore, the research by Stifler and Spinrad, looking at emotion regulation in 5- and 10-month olds, examined the role of prior excessive crying, presumed to be a temperamental trait, and found differences in the experience of distress based on that categorization.

Although we shouldn’t need science to tell us there are differences in the experience of distress by an infant, luckily we have it. What we now need to look at is how this experience of distress influences the use of self-soothing behaviours. After all, if the idea of sleep training is to get a child to learn to self-soothe, we’d better hope it does in the face of distress, right?

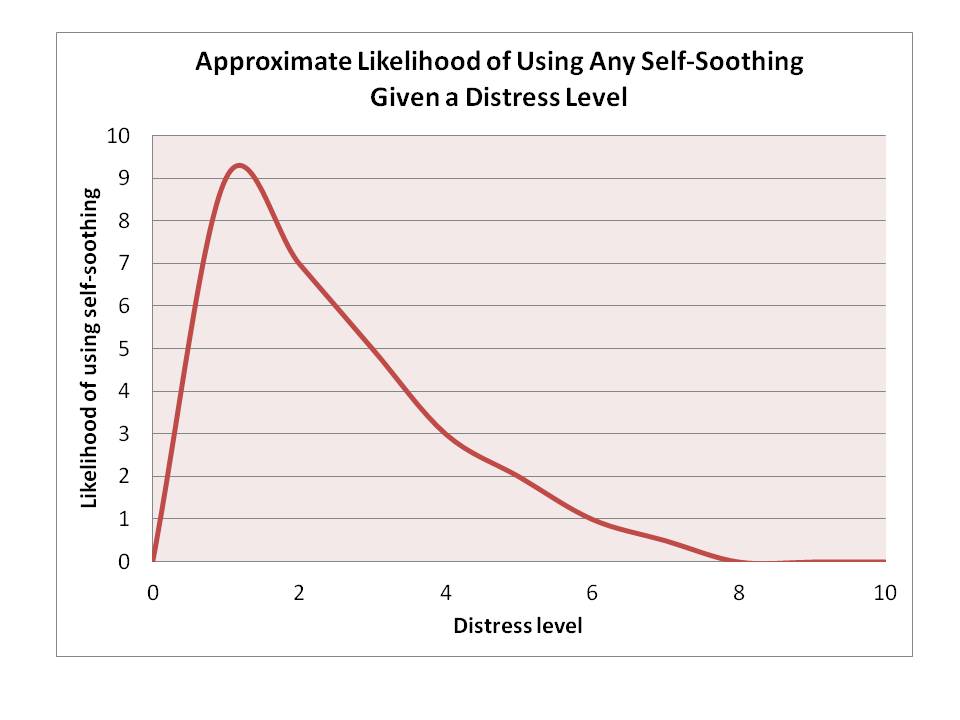

The problem with this is that in all of this research, the relationship between the experience of distress and the use of self-calming or self-soothing behaviours is inversely related. That is, the greater the distress, the less likely an infant is to be able to use self-soothing behaviours. In one research study, the negative association was very strong and this was not mediated or explained by maternal behaviours when the child was distressed (i.e., sensitive versus intrusive) or by child temperament. This is in line with older research that found the child’s degree of reactivity has a huge influence on their ability to use any regulatory behaviours (not just self-comforting, but even seeking out assistance or arching away). Indeed, the research on the development of emotion regulation consistently finds that infants are unable to use these behaviours except at low levels of reactivity or distress.

The role of temperament was also made clear in both those studies with young infants in that infants that were easily distressed showed lower levels of emotion regulation regardless of the immediate distress. Furthermore, babies that were rated as being easily frustrated showed greater physiological reactivity to distress and in turn, less physiological regulation to distress. The cluster of behaviours seen in the research (which also includes less attentiveness and distress to novelty) has the researchers suggesting a specific temperament pattern in which the development of emotion regulation may be slower and require more assistance.

If we take these findings and relate them to more modern research on sleep training per se, we may get a clearer picture. First, we should look at these issues of self-soothing and distress with respect to the research by Middlemiss and colleagues that looked at cortisol reactivity and synchrony during cry-it-out sleep training. These researchers found that during the extinction program, infants cries were associated with a very high spike of cortisol during the separation before sleep. Notably, by day 3, infants were no longer crying, but showed the same cortisol spike that they did on day 1.

One of the biggest concerns on this research, however, has been the high standard deviations in the group, which is indicative of high variability between infants. I hope the section here on distress helps to clarify this in that distress is highly variable. Some infants become very distressed to certain situations that others find only mildly distressing, if distressing at all. This speaks to the influence of temperament in the use of sleep training and any potential long-term effects. Indeed, research on parental care and stress responsivity more generally shows that infants who are more reactive show greater elevations in cortisol under conditions of less-than-optimal care (defined as sensitive and responsive care).

The second element of this study worth discussing is the effect on synchrony. In the Middlemiss and colleagues research, the physiological synchrony between mother and baby that was high and statistically significant on day 1 was dampened to the point of non-significance on day 3. Synchrony is important to development as it influences a host of outcomes pertaining to well-being, and is supposed to be present in caregiver-infant dyads. The loss of this synchrony was in fact the main finding of note in this particular piece of research because it highlights how disruptive extinction sleep training is.

If we go back to role of coregulation in emotion regulation, we can clearly see the possible negative effect of a loss of synchrony. Coregulation works because the infant is able to be calmed physiologically (even if not emotionally) by the caregiver; however, there needs to be a relationship that allows for this. A total lack of synchrony would mean the parent is unable to calm the distressed child at all. In cases where synchrony has been dampened, the ability of parents to physiologically soothe their infant will be diminished, but not absent. Returning to the quote above on how the child’s brain makes sense of cry-it-out in terms of parental abandonment, the findings on synchrony are in line with the view that it may have a significant effect. (The question now becomes, for how long?)

The second bit of recent research worth mentioning is that which examined the efficacy of sleep training done at home. Whereas most of the research on how effective extinction programs (i.e., cry-it-out and controlled crying) have been done in labs where there are very strict procedures in place, how this looks at home may be very different, and indeed that’s exactly what researchers have found. Instead of the quick fix that it is advertised to be, extinction programs at home were largely unsuccessful, with half of the people who tried it reporting having to try it 4 or more times and 40% of families reporting needing to use it for longer than a week before either success or giving up (nearly 13% used it for more than a month straight). On top of all this, 40% of families said it did not improve their infant’s sleep at all. Notably, the parents who reported that the technique was highly stressful for their infant were also those who found it least effective; knowing the link between distress, self-soothing, and coregulation, is this any surprise?

Putting It All Together

What does all of this mean? I can only tell you how I take it, you are free to come to your own conclusions. For me, this tells us two big things: (a) the idea that extinction sleep training methods will work for all children ignores a key variable, namely the degree of distress experienced by an infant during these methods, and (b) that this distress is a key indicator as to how the process of self-settling will impact the child, the parent, and the later emotion regulation.

Extinction works by taking away responsiveness until the child gives up. At its worst – straight up crying-it-out – it is a method that tells parents to ignore their child’s distress at all costs. No matter how securely attached their child is prior to this method, the lack of a parental presence means the child will experience a cortisol spike, the duration of which is unknown. How this affects their developing brain will be subject to a host of other factors – how long this goes on for, the temperament of the child, the degree of attachment after sleep training, and so on –so of course we can’t make definitive conclusions.

We can, however, say that self-soothing isn’t what’s going on during extinction sleep training. Whatever it is – self-settling or giving up – isn’t in the realm of emotion regulation as we know it. Given the link between distress and ability to regulation one’s emotions, causing a child immense distress is not a means to elicit or teach self-soothing.

A child who does not experience distress, however, is likely to be less affected by the process. Does this mean it should be endorsed for these children? I still say no. First, extinction methods aren’t often used if a child is going to sleep without distress on one’s own. What point would there be? So with this, it becomes difficult to argue that the method would even be appropriate to begin with. (If people are using it to stop night wakings, then I would really caution against that – if you have a child going to sleep independently and waking in distress, than I’d hazard a guess to say something else is going on because there are no cues you’ve been using that the child might be looking for.)

This is an updated version of the article “Distress, Self-Soothing, and Extinction Sleep Training” that was originally published in 2015.

Relevant References

Calkins, S. D., Dedmon, S. E., Gill, K. L., Lomax, L. E., & Johnson, L. M. (2002). Frustration in infancy: Implications for emotion regulation, physiological processes, and temperament. Infancy, 3(2), 175-197.

Campos, J. J., Frankel, C. B., & Camras, L. (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child development, 75(2), 377-394.

Eisenberg, N., & Spinrad, T. L. (2004). Emotion‐related regulation: Sharpening the definition. Child development, 75(2), 334-339.

Gunnar, M. R., & Donzella, B. (2002). Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27(1-2), 199-220.

Kopp, C. B. (1989). Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental psychology, 25(3), 343.

Loutzenhiser, L., Hoffman, J., & Beatch, J. (2014). Parental perceptions of the effectiveness of graduated extinction in reducing infant night-wakings. Journal of reproductive and infant psychology, 32(3), 282-291.

Middlemiss, W., Granger, D. A., Goldberg, W. A., & Nathans, L. (2012). Asynchrony of mother–infant hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity following extinction of infant crying responses induced during the transition to sleep. Early human development, 88(4), 227-232.

Porges, S. W. (1996). Physiological regulation in high-risk infants: A model for assessment and potential intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 43-58.

Rothbart, M. K., Ziaie, H., & O’boyle, C. G. (1992). Self? regulation and emotion in infancy. New directions for child and adolescent development, 1992(55), 7-23.

Stifter, C. A., & Braungart, J. M. (1995). The regulation of negative reactivity in infancy: function and development. Developmental Psychology, 31(3), 448.

Stifter, C. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2002). The effect of excessive crying on the development of emotion regulation. Infancy, 3(2), 133-152.

I love this piece. I do have a question, though not to do with sleep. You state that distress caused by the caregiver withdrawing care is processed as abandonment (understandably) – would this be for all situations where the caregiver is not or cannot be present? I am asking this as my daughter (who will be 10 months) will be starting nursery (or daycare as you may know it) this month, and she has never really spent a lot of time away from me. We do have a few ‘phasing in’ sessions, but she will not be used to any of the nursery carers – I worry that if (or more likely when) she gets distressed she will be unable to process it and will not have a bond with anyone present to help mitigate the physiological effects of the distress. I also am worried that it will affect our synchrony, which is currently strong. I do not want her to think I have abandoned her! I suppose my question is if your child is aware that you are not present at all (as opposed to sleep training, where an older baby may be aware that you are in another room but not responding) would this be processed differently by them? Thanks!

Actually its a bit more complicated. In terms of coetisol, we know children will not experience a cortisol strike if they are left for short periods (under half an hour) with someone responsive. This is one of the big reasons daycares should have transition periods. The child can develop their own attachment with a caregiver before mom leaving. Otherwise the issue of distress in daycare unfortunately does show altered cortical activity sometimes for months (though this was in older toddler children so again, it may differ for younger children).

I have been thinking a lot lately about the logic behind sleep training so I came back to this post. My thought is this. Why do we feel that children need help and direction when learning other life skills but not when it comes to sleep? If I told someone my child couldn’t swim, I doubt they would say, “Throw that kid in the deep end of the pool and walk away. He’s just going to have to learn to self-swim.” No. We would take time and patience to teach that child the steps necessary to become a successful swimmer. Why do we not do the same with sleep?

And where did the idea that crying is necessary for lung development come from?

[…] entrenamiento. Eso es patentemente falso. Todo lo que puedo hacer es recomendar que lean sobre la influencia del desarrollo del autoconsuelo en relación con el entrenamiento para dormir, las diferencias individuales en la experiencia del […]

[…] anyone wanting further background reading, this is my favourite blog post. Non judgemental, fully backed up with research and containing helpful alternatives to sleep […]

[…] regulation required to settle themselves from a place of distress. Sarah Ockwell Smith and Dr Tracy Cassels do a fabulous job explaining […]

[…] Mama, I so have been there. If that’s the case, you may be ready to try sleep training—extinction, Ferber, cry it out, or whatever name you’re using. And if that’s true, you need to […]

[…] Evolutionary Parenting With TracyCassels PhD: Distress, Self-Soothing, and Extinction Sleep Training Jean Liedloff – The Continuum Concept: In Search of Happiness Lost (Da Capo Press, 1985) var […]

Hi, I am a first time father with a nearly 6 month old girl. My partner and I are constantly discussing/arguing about the best methods to get our little girl to sleep. I am a bit old school, I have always believed, and have been told by people that controlled crying techniques are the best method. However my partner doesnt agree with it.

I would like for us to agree on something so we can work together, and so ive been reading articles like this one in the hope I will change my opinion. My question is, what long term evidence is there that extinction sleep training has a negative effect on the child/children? Are there any correlations between mental health issues and controlled crying?

And without letting our baby cry, how do we get her to sleep? Just hold her and wait?

Thank you.

In terms of long-term evidence, there is none simply because there is no research on sleep training and long-term outcomes except one study that was so poorly done that they ended up with two groups that were made up of people who did the same stuff! So what we have is looking at outcomes for stress – chronic and acute – and how those affect behaviour. Some early research does raise flags, but as I’ve said in talks, what we really have is a lot of circumstantial evidence and nothing too clear cut either way because the research hasn’t been done.

As for sleep, I highly recommend a few books with excellent suggestions and recommendations. They are:

The Discontented Little Baby Book by Pamela Douglas

BabyCalm by Sarah Ockwell-Smith (and the Gentle Sleep Book by the same author)

The No-Cry Sleep Solution by Elizabeth Pantley

A final note: You actually aren’t “old school” 🙂 The advent of controlled crying is very new in terms of human history and even cross-culturally it’s not “a thing”. It’s a relatively new, Western phenomena that goes back 100 years or so compared to the hundreds of thousands of years of humanity. 🙂

[…] • https://gku.flm.mybluehost.me/evolutionaryparenting.com/distress-self-soothing-and-extinction-sleep-training/ […]

[…] is plenty of evidence and research to show that our little ones aren’t supposed to sleep all through the night. But […]