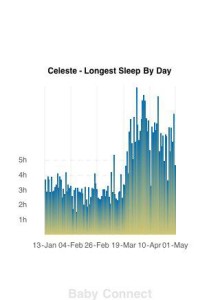

There are two public health battles ongoing in most Western countries today: Breastfeeding and bedsharing. For the former, the public health goal is to get more women breastfeeding for myriad reasons. For the latter, there has been an intense push to get women to keep their babies out of their bed, with some even calling for criminal charges to be laid against those who don’t abide. The problem is that these two acts traditionally co-exist. Most breastfeeding women will tell you that the only reason their sanity isn’t entirely gone after having a new baby is because of bedsharing, as this one mom’s nighttime sleep log demonstrates so eloquently (guess when she started bedsharing):

Photo Credit: Celeste

Having your baby close by makes for those inevitable nighttime feeds to happen faster and without the baby rousing entirely. At the BC Lactation Consultants Annual Meeting in 2015 Dr. Helen Ball of Durham University showed a video of mothers and their babies in different sleep environments to show the cues infants give to nurse and how they are responded to in different environments, namely bedsharing or room-sharing. Perhaps not surprisingly, the bedsharing mother was able to pick up on her infant’s nursing cues before her baby truly woke up and signaled, something that was absent even when baby was asleep in a cot right next to mom’s bed.

This ease of nursing and hyperresponsiveness is likely why babies who bedshare feed more at night than those who do not. But what about the relationship to breastfeeding full-stop? Some have suggested that not only can breastfeeding and bedsharing go hand-in-hand, but that they inherently must. That if we shut down bedsharing, we also shut down breastfeeding (at least to a large degree); in essence, we have two public policies that may be at odds with each other.

Looking at this very issue are two pieces of research from the UK and USA. Both attempt to examine this and come to somewhat different conclusions. To better understand what each of these pieces of research can tell us, let us delve deeper into what both have examined and what both can tell us.

What was the research question for each study?

In the UK, Dr. Helen Ball and colleagues were looking at the question of which groups of women were more likely to bedshare and to examine the relationship to breastfeeding outcomes[1]. The USA study, led by Dr. Lauren Smith, aimed to look at the relationship between both sleep guidelines and breastfeeding advice and actual practices as well as the interaction between the two[2].

As you can see, the aim of each study was different and thus the information they provide is different. When we’re looking at the relationship between bedsharing and breastfeeding, each of these studies provides some information, and together I believe they offer us a good first look at what the overarching question of interest.

What was the design of each study?

In the UK study, 870 mothers were recruited at birth (for another study on sleep location in hospital) and then were followed up for 26 weeks (6 months; though 24 weeks were used in the analysis for uniformity). The current study is based on parent reporting of breastfeeding and sleep location every week via an automatic survey. In addition to weekly data, prenatal feeding intentions were recorded as they were likely to influence breastfeeding outcomes.

Bedsharing was defined as bedsharing at least 1 hour per week. The researchers did attempt to examine bedsharing by days, but had so much missing data, they had to exclude the variable and these were categorized into 4 groups including ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘occasionally’, and ‘frequently’ based on the number of weeks they reported bedsharing at least 1 hour. Breastfeeding data included both exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding data in weeks (up to 24 weeks). The data was examined to determine if bedsharing had any relationship to breastfeeding duration, both exclusive and partial, and how intention to breastfeed played into this relationship.

In the USA study, over 3000 mothers were recruited at hospitals and agreed to take part in a follow-up survey when their baby was approximately 2-months-old. The question was to look at the advice women received regarding sleep location (or safe sleep practices) and breastfeeding then compare this to their actual behaviour. The sleep section was designed to look at whether the advice women received by four different sources (family, media, baby’s doctor, and nurses at the hospital) complied with the AAP guidelines of no bedsharing or solitary room sleep, but room-sharing, and if following this advice influenced breastfeeding. Of note, because both bedsharing and solitary sleep are against the AAP guidelines, these conditions were combined for the advice analyses and recommendations, a potential problem.

What were the conclusions of the UK Study?

In this study, of the women with bedsharing data, 44% never or rarely bedshared, 28% did so occasionally, and 28% did so often. Women who bedshared continued breastfeeding for a longer duration, with the cessation time of breastfeeding being 14 weeks for no bedsharing, 24 weeks for intermediate bedsharing, and over 26 weeks for regular bedsharing (3, 5, and 10 weeks for exclusive breastfeeding). I say “over 26 weeks” because the study ended at the 26 week point.

Does this mean that bedsharing promotes breastfeeding? We don’t know and Dr. Ball and colleagues readily admit this in the paper. What can be said is that it seems that bedsharing is a strategy used by women who breastfeeding. In line with this, a stronger intention to breastfeed was associated with more frequent bedsharing, suggesting that women who have a strong intent to breastfeed incorporate bedsharing into their nighttime feeding strategy. This may be that women who have a strong desire to breastfeed have done their research and are aware of the need of nighttime feeds and have found bedsharing to be the way to allow them to provide those feeds while also allowing them to obtain sleep. However, the fact that quite a few families were breastfeeding for a longer duration without bedsharing does show that bedsharing is not inherently needed for a successful breastfeeding relationship. Furthermore, there were a significant number of bedsharing families who weaned early and thus bedsharing may not be the panacea to breastfeeding that has sometimes been implied. As stated by the researchers,

“The results of this study do not support previous arguments that bed-sharing protects against early weaning. They do, however, raise the question of whether recommendations to avoid bed-sharing impede some women from the achievement of their breastfeeding goals.”

At the end of the day, I believe that last point is the take-home message here: Anti-bedsharing messages very well might hurt some breastfeeding relationships in cases where women need that sleep setup to both feed with the regularity their child needs (some babies feed a lot during the night) and get enough sleep to function the next day.

Source: ISIS Co-Sleeping Image Archive

What were the conclusions of the USA Study?

The amount of advice in line with the AAP Guidelines increased the odds of following their sleep location and breastfeeding advice in a dose-response, such that the more sources that provided that information, the more likely families were to follow it. This was particularly true for breastfeeding, where the odds of breastfeeding at 2 months (exclusive or partial) was 4.46 times greater if 3 of the 4 sources advocated for breastfeeding and 5.67 times greater if all four sources advocated breastfeeding. This highlights the incredible influence that those around us have on our choices in parenting. A mother can want to breastfeed, but her chances of being successful early on (as this study ended at 2 months) are influenced by the thoughts of and bits of advice given to her by others.

With respect to the question of bedsharing and breastfeeding, the authors argued that the advice to room-share over bedsharing did not negatively influence breastfeeding rates, thus bedsharing and breastfeeding don’t need to go together. Interestingly, however, 42% of exclusively breastfeeding mothers were bedsharing; compared to those not bedsharing, there was a 146% increase in odds of exclusively breastfeeding when bedsharing (and the odds of breastfeeding were lowest amongst those whose babies slept in a different room at 2 months). Of course, this alone does not mean that bedsharing is necessary, but it does suggest that early on, it is a strategy that many families use.

There were also a few issues worth noting:

- Although the researchers assessed the advice given to women, they did not assess whether or not women took this advice on an individual level and how this interacted with breastfeeding (or bedsharing, depending on the framing of the question).

- Breastfeeding was defined herein as breastfeeding at the breast or the use of exclusive pumping. With respect to the relationship to bedsharing, it is more likely that bedsharing becomes an important strategy for women who are breastfeeding from the breast and thus this would need to be filtered out.

- The authors claim there was no dose-related response of advice on the interaction of practices (breastfeeding and bedsharing); however, the rates suggest something different. That is, based on sleep-location advice, we see an inverse-U shaped curve for the rates of exclusive breastfeeding, with the lowest rates of exclusive breastfeeding existing amongst those who received the strongest amount of sleep location advice (to room-share but not bedshare). It’s unclear what this means or how families interpreted it, but it definitely leaves open the idea that strict advice against bedsharing may harm.

In sum, this study did actually find a relationship between breastfeeding and bedsharing, but certainly did not find that bedsharing is necessary, but again, like the UK study, would suggest it is a tool families use when breastfeeding. And as just mentioned, strong, blanket advice against bedsharing may actually hurt some families who are looking to breastfeed.

What else of interest came from the studies?

As with all studies, the main question is of interest, but there is often information that is of interest outside that main question. Both of these studies include such information.

Most of this “interesting” information is to do with breastfeeding and these studies highlight a lot of reasons why breastfeeding advocacy is still very much needed in our society. For example, in the UK, only 66% of women initiated exclusive breastfeeding (didn’t complete it, but simply initiated it) and in the US, at 2 months, only 30.2% of mothers were exclusively breastfeeding (and another 29.5% were partially breastfeeding). In the UK the longest average of exclusively breastfeeding was 10 weeks (2 months) for the usual bedsharing group and this fell to 3 and 5 weeks for the other groups. This means the vast majority of mothers are not exclusively breastfeeding for the 6 months recommended by the WHO.

Now you may be asking should this matter if this was a woman’s individual choice, and you’d be right to ask that; however, the prenatal intent to breastfeed was quite high in all groups, but the reality was very different. This speaks to the many barriers that still exist to allowing women to realize their own choices when it comes to breastfeeding. The USA study speaks to one of these barriers as 7.5% of women reported that the majority of advice given to them was against breastfeeding. For these 7.5% of women, a minimum of 3 of 4 sources told them breastfeeding was bad and not to do it and for some of these women, all 4 sources (meaning it includes their doctors and nurses) told them not to. That’s like having a doctor tell you that exercise is overrated and you shouldn’t do it. Scary. Of course, this also was associated with a reduction in odds of breastfeeding as these women who had a negative score were 70% less likely to exclusively breastfeed compared to those who even just had a neutral score (that is half suggested it, half didn’t; the odds would be much less compared to those who had advice to breastfeed).

What is the take-home message?

There are two messages here that we should take home from this research: First, bedsharing is a strategy used by many breastfeeding families. Despite the dire warnings not to bedshare, it is something families will continue to do and seems to go with breastfeeding without being necessary for breastfeeding. This relationship, however, complicates public health messages that promote breastfeeding while decrying one the strategies that assists some families meet this goal without losing their sanity. The question about the validity of anti-bedsharing messages in the UK study is tangentally supported in the USA study where lower exclusive breastfeeding rates were found in those groups where the advice against bedsharing was strongest. However, far more research is needed to make any firm conclusions on the matter.

Second, breastfeeding advocacy is needed. Time and again we see women’s intentions to breastfeed not match the reality they find themselves up against a few months postpartum. When this happens, there are many plausible explanations, but almost all of them will in some way relate to a society that does not support mothers both more generally and in breastfeeding. Breastfeeding takes time, adjustment, and support and when women are lacking support in breastfeeding specifically, but also when support more generally is lacking, breastfeeding can seem like one of the easier things to give up, even if it’s something a mother wanted to do. We have other evidence that women are unable to meet their breastfeeding goals (e.g., [3]) and the research herein simply supports the view that we need to change a lot before women are given the real opportunity to breastfeed if they like.

______________________________

[1] Ball H, Howel D, Bryant A, Best E, Russell C, Ward-Platt M. Bed-sharing by breastfeeding mothers: who bed-shares, and what is the relationship with breastfeeding duration? Acta Paediatrica 2016; 105: 628-34. [2] Smith LA, Geller NL, Kellams AL, Colson ER, Rybin DV, et al. Infant sleep location and breastfeeding practices in the United States: 2011-2014. Academic Pediatrics 2016: doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.021. [3] http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/breastfeeding2015/index.html[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Disgusting that any thing like nefsharing which is so inline woth a secure attachment cpuld br under threat and become illegal. All because of a few dimwits