When you write about science articles, there are bound to be some things that people just don’t get. If you haven’t taken part in research, then understanding the nuances is something you’ve probably never considered (why would you?). This means, though, that people make comments and reach conclusions without fully understanding what it is that’s being highlighted by the research. I encounter comments like these frequently through no fault of the individual who makes them because, if I were in their shoes, I’d probably think the same way.

The thing is, it’s hugely important that we do understand what science is saying if we’re going to use it to help people understand the potential outcomes of their parenting choices. If people don’t understand the findings or think they’re wrong because it doesn’t fit with what they see day-to-day, then we fail at educating parents. So here I’d like to tackle the top 3 misunderstandings I’ve encountered in hopes people can understand what it is that’s really being said.

1. Comparing Kids

The most common misunderstanding is when people start comparing their own kids to others in an effort to support or refute the research. And most commonly it happens with respect to discussions on breastfeeding. I hear people say things like, “My children were all formula fed and they’re no further behind the kids I know who were breastfed.” In some ways, they can be correct. Yes, formula fed babies can be healthy and smart. Breastfed babies can be no different than their formula-fed peers with respect to health and intelligence. But that’s not what the research is really saying. And this becomes very difficult because the research talks about “breastfed babies” and “formula fed babies” so why wouldn’t we make these comparisons? It all comes down to control.

What does this mean? Well, in research you can’t just take two groups, especially two groups where people self-select into what group they belong to (like nearly all parenting practices), and compare them. Why? Because there are so many other factors that will influence why people chose one practice over the other and these may affect the outcome variable as well. For example, income is closely tied to both breastfeeding and health outcomes – families with more money tend to breastfeed (presumably because mom can stay home to breastfeed; this may change with new pumping laws) and tend to have better health (presumably because they can afford better health care and better foods, medicine, exercise, etc.). There are also the variables that just affect the outcomes of interest, whether or not they’re related to the group one self-selects into. For example, having older siblings increases a baby’s chance of being exposed to more germs and thus to get more colds and illnesses. While having multiple children doesn’t affect the group one might belong to, it remains an issue that needs to be considered in the research. So any comparison has to account for these other factors to ensure the relationship of interest isn’t spurious.

How does research do this? The best way is to randomly assign people to each group that you’re interested in studying. So for breastfeeding, we would hope to get a large enough sample that’s representative of the population and then randomly assign families to either a breastfeeding or formula feeding group. This way, you hope that the random assignment deals with all of these other confounds. But when you can’t randomly assign groups you have to statistically control for these other effects and that’s what most research does nowadays. When people study breastfeeding, they measure income, ethnicity, and a host of other factors in order to control for their possible effects. This is why it’s so important to read the entire article and not just the abstract, because only then will you know exactly what they controlled for and how much weight you can give a particular article.

At the end of the day, what the research is really saying is not, for example, that children who are breastfed will be smarter than formula fed infants, but that if you take two children with the exact same situations and you breastfeed one of them and formula feed the other, the formula fed child will generally be [less healthy/less intelligent/fill in the blank]. There’s a huge difference and this is why I’ve often tried to explain to people that the comparison is really about within individuals because no other child, siblings included, will have the exact same characteristics as any given child. So what you can take from it is that, given the genes and environment your particular child has, a particular parenting practice will lead him or her to generally be more or less healthy/intelligent/whatever than he or she would be if you had made a different parenting choice. And sometimes the difference may not be that great given a particular child’s genetic makeup, and sometimes it could be the difference between life and death. How we discover the individual effects, however, is still unknown.

2. Anecdotes as Data

This one you’ll hear everywhere and is the more general case of the first situation of comparing kids – the personal stories that are supposed to inform our decisions about what is best. Parents who formula fed and have highly intelligent children. Parents who co-slept and had a baby die. It can range from the mundane to the horrific, but in common is the idea that research speaks in universals and thus a single anecdotal story (or even several) serves to negate the general findings.

While anecdotes are obviously used as comparisons, they can also be used without that said purpose. In many instances, people speak of their own experience as proof that what science says isn’t so; therefore, the problem is not only that group comparisons are bogus, but the erroneous belief that findings from research dictate what will happen. And that’s just not the case. All research speaks in terms of probabilities, not certainties. I like to pull the smoking card out here… The vast majority of people will agree that smoking can cause cancer. But this does not mean that smoking will cause cancer. Most of us know many people who smoked for years with no ill effects, just as we know people who were diagnosed with lung cancer who never smoked a cigarette in their lives. But if you smoke, the chances that you’ll develop lung cancer are far greater than if you don’t.

The same applies to parenting. No single practice (perhaps barring the absolute extreme like abuse, but even then the actual effects will vary individual to individual) will have universal consequences, regardless of what you might hear or believe. What research shows us is that things are more or less likely to happen depending on the way in which you parent. The anecdotes as data is typically brought out in scare campaigns, like those against co-sleeping—women sharing the horror of waking up next to a dead baby in hopes it gets people to stop co-sleeping. But research (good research) isn’t on their side. When studies have included controls (see point 1), co-sleeping has been found to be as safe as putting your infant in a crib in your room. In fact, studies show that putting your child in a crib in a different room is what raises the risk of SIDS (see Bedsharing and SIDS: The Whole Truth). Home birth is another area in which people use anecdotes to scare—certain people speak of the horrors that can happen when a woman isn’t in a hospital and yet research shows that for normal pregnancies, home birth is as safe or safer than a hospital birth (see Fighting for Homebirth).

At the end of the day, we have to realize that science is not a magic crystal ball. It can’t spell out our future. All it does is tell us what is more or less likely to happen when we make certain decisions. And that’s a big difference.

3. The Average

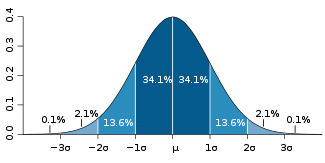

One of the statistics that is most commonly reported in studies is the mean, or average. We read about average everything in order to understand the generalities that the researchers found, and yet many people seem to forget that an average is only that – an average. Surrounding that average are “normal” cases which extend to either side of that magic number. It’s called a normal distribution and it looks like this:

For any variable, there’s a normal range of scores that we can expect—whether it be number of hours of sleep, length of labour, times a baby breastfeeds, etc.—but what gets reported is only the middle number, the one that all others centre around. And people who aren’t right at or extremely near that number tend to panic, even though the point of the “normal” distribution is that all the values in that distribution are “normal”.

For any variable, there’s a normal range of scores that we can expect—whether it be number of hours of sleep, length of labour, times a baby breastfeeds, etc.—but what gets reported is only the middle number, the one that all others centre around. And people who aren’t right at or extremely near that number tend to panic, even though the point of the “normal” distribution is that all the values in that distribution are “normal”.

The two cases I see this the most are with respect to infant sleep and labour. For infant sleep, the problem is parents panicking that their infant isn’t hitting a magic number of sleep that is typically provided by “experts” and based on means of studies. These experts take values like the average and declare that babies need to be getting that amount in order to be “healthy”. Yet they themselves seem to have forgotten that there were many other babies who were healthy and who failed to reach that magic, yet average, number. The problem is not that parents shouldn’t be concerned with sleep, but rather that parents need to focus on their own child’s behaviour for signs of sleep deprivation. One child can get 9 hours a night and be fine while another gets 12 hours a night and still remains sleep deprived. In my own opinion, instead of looking at numbers, parents should be given information on how to identify sleep deprivation across ages. That should help them more than any single number will.

The second concern, labour, isn’t a problem parents bring up, but it certainly affects them because it’s how doctors have interpreted the data. The biggest example of this is the Friedman-curve of length of labour which was based on data collected by Dr. Friedman and reports averages. The curve was then taken to justify the use of drugs to speed up labour and the mass use of c-sections for “failure to progress” when women “fell off” the curve. Interestingly, from what I have been able to discern, Dr. Friedman hated the use to which his curve was put as he firmly believed it was a tool to inform, not dictate. That is, he believed doctors should be aware that if a patient falls off the chart she is more likely to require interventions, but not that they should be given because she’s fallen off the chart. The problem seems to be the same as for parents with a child who doesn’t sleep the right amount—doctors aren’t looking at the symptoms or the individual, they’re looking at numbers. You’ve been pushing for 2 hours (currently the magic number at most hospitals because it’s considered far enough above the average to mean something)? That’s now too long and so you need something to speed it up, even if there is no other indication that something isn’t right. Like parents who need to read their child, doctors need to read each labour because a pushing stage where no one shows any distress and baby keeps moving shouldn’t be altered because it’s gone on “too long” and mothers who show no other sign of distress or problems but who have been in stage one labour for over 14 hours should not be c-sectioned. It’s ridiculous and it’s harmful.

It’s up to parents, doctors, and midwives to remember that an average is an average and there will be values that are normal that lie on both sides of the average. And that’s okay.

Conclusions

What does science tell us? Science can’t tell us exactly what will happen, but it can provide us with likelihoods and some information to guide our decisions in this science-loving world. And because science can’t tell us what will happen in our particular situations, it’s up to parents to make their own decisions after hopefully looking at the factors that are salient for them. It’s why I like to look at history and science together; what did we do and why? And how can science help us understand how our current environment may affect practices that are as old as humans?

The more we understand what science can tell us, the better educated we can become as parents. This means we can take the studies for what they’re worth and know how to apply it to our own lives. And most importantly, we can learn to both not worry when we don’t think we’ve fit what a given study finds and also know that it doesn’t discount the research altogether.

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

What a perfectly cogent and long overdue blog post (not on your part, but on behalf of the science community in general)! As an academic but also a new mom I constantly have to remind myself of these very same pratfalls.

And double thank you for the smoking card! I’ve seriously heard people argue that since there’s been no double-blind random control study of formula- vs. breastfed infants, there’s no ‘proof’ that breastfeeding is ‘better’ than formula feeding. All of our knowledge about healthy lifestyles today comes from observational studies and natural experiments–from smoking cigarettes to eating high-fat/high-carb diets to shooting meth while pregnant–yet nobody would seriously argue that there’s really no ‘proof’ that smoking can lead to cancer, McDonald’s is actually good for your health, or that shooting meth in your second trimester is really not such a bad thing…..

I absolutely agree. I have found myself arguing these points many times over. In particular your first point.

It would be nice for everyone to understand scientific research, and to understand when it is being used to deliberately mislead the public – something I’ve found that happens too frequently. And it would definitely help to reassure new parents when their babies aren’t typical ‘average’ babies. I know I worries about my eldest still not speaking at 2 1/2. He’s now 3 1/2 and far excels his peers, he is able to read without assistance, can explain the formation of volcanoes etc. I’m certainly not worried now. My son has shown me first hand that I was wrong. But in the grand scheme of things I don’t think it REALLY matters.

However when it does matter is when medical professionals don’t understand the data they are given. Averages are a great case in point. I am quite tall, but naturally very slim. The midwives were very concerned that my bump was measuring ‘small’ compared to the averages that they work to and I was sent me for a growth scan. This happened 3 times in 6 weeks. They couldn’t understand that although I was ‘small’ my bump was growing at exactly the right rate, so it would be small each week. They were too fixated on averages to use any common sense. My baby was 8lb 2oz so I was right not to worry. This is a trivial matter but it is concerning.

Great article. I just wish the right people had this understanding.