When you talk about sleep training – specifically extinction sleep training like cry-it-out and controlled crying – you get a lot of people talking about stress on both sides. On one extreme you get the idea that all stress is equally bad and thus any stress for a baby is bad. On the other you get people suggested that the stress of sleep training is at worst benign and possibly even beneficial. Across the spectrum, there’s a lot of misunderstanding about stress and the research we have that speaks to it, especially as it pertains to infants. As such, I’d like to clear up a few common misunderstandings here on what we know and don’t know about stress and the implications for sleep training.

Minor Stress is Beneficial

One of the biggest arguments I have heard in favour of extinction sleep training is that a certain amount of stress can be beneficial. Yes, we know that individuals actually learn when they are mildly stressed[1]. We absorb more information about our surroundings and then retain that information better than we would otherwise (it’s why last minute cramming actually works to a certain degree). When we are stressed and have to learn something, we often do in ways we didn’t think possible.

One of the biggest arguments I have heard in favour of extinction sleep training is that a certain amount of stress can be beneficial. Yes, we know that individuals actually learn when they are mildly stressed[1]. We absorb more information about our surroundings and then retain that information better than we would otherwise (it’s why last minute cramming actually works to a certain degree). When we are stressed and have to learn something, we often do in ways we didn’t think possible.

But the question is how this applies to infants. You see, there are actually two issues that limit the ability to apply our knowledge of stress to infants. The first is what researchers call external validity (specifically population validity). This means how well one can extrapolate findings to various populations. In research on stress, we don’t have evidence from infants as to the “benefits” of minor stress, and it is questionable as to how applicable research with adults is. This brings us to another point: Research with adults and children is based on a relatively-developed brain. In fact, research on stress shows us that the more developed the brain, the lesser the effects because coping mechanisms have developed. This is why we worry about the types of stress we expose our children to as we are well aware they don’t inherently have the ability to cope independently. So the idea that minor stress is beneficial has to be taken with the knowledge that we know this to be true for certain populations. (As an aside, there is also the issue that sometimes major stress is not associated with long-term negative outcomes because how we cope with the stress involves myriad factors[2] and this we can’t consider the stress without considering the coping mechanism.)

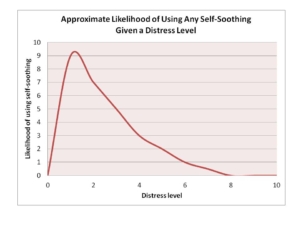

Now, let’s assume it holds for infants. This brings us to the second issue: What is minor stress? Often when we talk of minor stress, we talk about the events that can cause us discomfort but not full-on distress. If your infant is screaming out for you, they are in the distress zone and likely very far away from “minor stress”. So let’s not kid ourselves that an infant crying because evolutionarily speaking, this baby fears for her survival is somehow “minor”. This brings us to the next argument…

Short-Term v Chronic Stress

If the stress that a baby experiences during extinction sleep training isn’t “minor”, does it immediately mean it’s the worst kind of stress?

No.

I know that there are those against sleep training who paint the picture of this kind of stress as being about the worst thing that can happen to an infant, but the fact remains that although this may very well be true for some infants (we’ll get to this), it’s by and large not the case. There are worse things that can happen. That still doesn’t make it right.

In this vein, many individuals try to claim that extinction sleep training is a form of short-term stress and then compare it to the well-known negative effects of chronic stress. When we think of chronic stress, we think of major stressors like emotional abuse, neglect, and so on. But chronic stress can be minor and it can wreak havoc on our lives and overall health[1]. In terms of early childhood experiences, some researchers have hypothesized that repeated minor stressors in the context of loving relationships can still influence long-term stress responses via a “kindling” effect[3][4]. That is, like a fire that needs lots of small pieces to burn effectively, later maladaptive stress responses can arise from lots of experience with these minor stressors. Each minor stressor may be “short-term”, but they cumulate to result in a much larger problem.

Outside of the kindling hypothesis, there are several other considerations that raise concerns about the idea that short-term stress is somehow okay for an infant:

- Adult versus baby. The research on the “positive” effects of short-term stress are done with older individuals and thus again, the ability to extrapolate these findings to infants is inherently limited given the lack of brain maturation that is likely necessary to make these effects possible.

- “Positive” effects? The question of how positive these effects are needs to be mentioned here as the positivity of the effects is only insofar as there is a real stressor. That is, when we experience stress without anything to stress us, even short-term, this is not inherently healthy. For infants who experience this stress when they are safe, we have to raise the question of how good this is for them and their developing brains to perceive a safe, innocuous event as threatening.

- Timing. As discussed extensively in Dr. Bruce Perry’s book The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog, we are incredibly unaware of the timing of neurological development and thus how certain events can have greater or lesser effects depending on the neurological development occurring at a particular time. What this really means is that what we think of as a relatively minor stressor can have a profound impact if it occurs at a particular point in neurological development (and likely along with other factors, to be discussed below). Heck, this happens with adults too when short-term stress is acute enough for the individual. Take a car accident as an example. It happens once, is very short-term, but can result in severe long-term psychological problems via PTSD. Not for everyone, but definitely for some.

- Temperament. This is another crucial factor that is often overlooked by those justifying extinction sleep training techniques and likely interacts with timing to predict the risk of negative outcomes associated with a given stress response. The idea that all children handle stress in the same manner is patently false. If you have the opportunity to talk to parents of children with certain disorders (e.g., Sensory Processing Disorder, Autism) or of a certain temperament (e.g., “higher needs”, sensitive), you will hear the stories of how more modern behaviourist techniques not only don’t work, but often cause myriad problems. This is because a child’s temperament will influence the degree to which he is influenced by the techniques used by his caregiver. As one example, the highly sensitive child has been described in research as suffering negative outcomes if given anything “less than optimal” in terms of sensitive and responsive parenting[5].

- Is it really “short-term”? When people suggest that extinction sleep training is “short-term”, I urge them to read a very telling report by researchers in Canada who seem to have found that on average it really isn’t[6]. In fact, most families weren’t “successful” with their sleep training over a short period and a significant minority of families continued their attempts for over 3 weeks. This is hardly “short-term”, especially in the life of an infant. In fact, the entire idea of “short-term” for an infant is something worth exploring further as we just don’t have the data on what constitutes short-term, minor stress for our youngest and most vulnerable people.

When we look at all these factors together, hopefully it’s clear that we cannot fully predict how a given child will respond to sleep training, even if the stress of it happens to be short-term because the child has “learned a lesson” early on.

(I also want to point out that while many families report young infants sleeping through after extinction sleep training, certainly not all do given the relatively high failure rate and still more of these families end up with further sleep problems with toddlers and preschoolers that require further interventions. The fact that we, as a society, view continued sleep problems as something normative is wholly problematic and not something that is witnessed universally around the world.)

Stress Inoculation

Certain people cite the idea of stress inoculation as evidence that minor stress in early childhood is beneficial. This idea stems from research with squirrel monkeys which has found certain stressful experiences in early life seem to confer benefits in terms of later responses to stress[7]. In fact, as the “stressor” used in these studies often involves separation, it can seem like the perfect analogy for sleep training in human infants, right? Actually, there are a couple problems with taking this research to apply it to infants experiencing sleep training.

Certain people cite the idea of stress inoculation as evidence that minor stress in early childhood is beneficial. This idea stems from research with squirrel monkeys which has found certain stressful experiences in early life seem to confer benefits in terms of later responses to stress[7]. In fact, as the “stressor” used in these studies often involves separation, it can seem like the perfect analogy for sleep training in human infants, right? Actually, there are a couple problems with taking this research to apply it to infants experiencing sleep training.

- These studies with this particular type of squirrel monkey mimic what happens in the wild (there are two kinds of squirrel monkeys with different parental care behaviours). That is, once these monkeys are newly weaned (around 3-6 months of age), they experience brief, intermittent separations from their mother while she (and others) forage for food. Put in perspective, these “young” monkeys are already weaned when mom goes foraging for food and already are spending more time with other young monkeys than their mother[8]. In short, what the researchers have found is that deviating from the norm for this species is associated with worse outcomes. This norm is different from our closer relatives, such as chimpanzees, who have an extended mother-infant dependency period, or humans who also have an extended dependency period[9].

- The separations are brief, lasting one hour, and take place during the day, not at night, and only take place once a week. The timing of the separations clearly matters as being left for 1 hour versus 12 is a significant difference, especially given the lack of a young infant to understand time. However, the time of day is also important as we are primed to be more fearful at night than during the day. Darkness is something humans have a natural fear of and so leaving our infants in a fearful environment for an extended period goes beyond what the research with squirrel monkeys can attest to.

If we compare this to humans, really the comparison would be more akin to a toddler being left for an hour once in a while during the day. So far as I know, no one who opposes extinction sleep training is opposed to that type of short-term stressor (barring the risk of a child harming him or herself if left alone, of course).

In fact, we must also return to the work of Dr. Bruce Perry on early life experience and trauma because the type of separation that is done during extinction sleep training is more akin to a case he described in The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog, in which a young child was left with a babysitter who left the baby in the crib alone and ignored him during the day. After work, he was loved and cared for by a loving, responsive family. That is, he experienced the type of stress of separation for 8 hours a day (less than the nighttime separation), but it occurred in the context of an otherwise loving and responsive relationship. Yet this boy suffered trauma, problems with empathy, and other effects that we would not wish on our children. Would all kids respond the same? No and that brings us back to the factors mentioned above that influence the stress response.

The Period of Hyporesponsivity

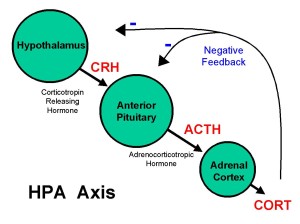

I have written in detail on the period of hyporesponsivity (you can read that here), so I will only briefly discuss here, but strongly suggest you read up on in more detail, here or elsewhere. What is the period of hyporesponsivity? It is the time in development (around the first 2-3 years) in which infants and toddlers will show a behavioural response to a minor-moderate stressor, but no associated cortical response. That is, the child cries and is distressed, but does not have a physiological stress reaction; there is a behaviour-physiology mismatch.

Importantly, not all minor-moderate stressors will be covered under this. Crucial to the discussion at hand, one of the immediate ways to elicit a cortical reaction is to separate the child from a responsive caregiver. That is, it seems that the reason infants and toddlers can experience the period of hyporesponsivity is that they are being cared for in a responsive and sensitive manner. In extinction sleep training, it is that responsiveness and sensitivity that is being taken away. Perhaps even more importantly, this research is done on human babies, not other animals with different natural parenting behaviours and developmental trajectories.

This is pertinent when we look at the types of stress that various people argue children can handle in the context of a loving relationship. People speak of children surviving the loss of a parent, war, extreme poverty, and more, but this ignores (a) that survival is not thriving and we have evidence that children hardly thrive in the face of such hardships[10][11], and (b) that children are able to cope with these events when there is a sensitive and responsive caregiver. Even the temporary removal of the responsive and sensitive caregiver can have profound effects on a child’s well-being.

Where Does That Leave Us?

Well, it depends. On a lot. Personally, I take the research on the period of hyporesponsivity and the effects of trauma far more seriously than the conjecture that adult stress will manifest equally in an infant with a rapidly developing brain. Of course, I also acknowledge that we don’t have a smoking gun regarding extinction sleep training and stress, and likely never will. Why? The primary issue is that stress and the stress response are so complex that we can’t narrow it down to a simplistic study. Even just the role of temperament alone is difficult enough to properly control for, yet we know it along with things like developmental delays or disabilities have a profound effect on stress.

This is why anyone who claims studies show no adverse effects is clearly speaking out of turn and does not understand the research as it has been done. I have written on this at length (see here and here), but there are no studies that have adequately looked at long-term effects of extinction sleep training. The closest was a study by Price and colleagues[12] that purported to look at outcomes years later, but the methodology was so flawed, the only conclusive thing that could be said was that they ran something that looked like a study.

So we are left in a zone whereby there is no smoking gun and a fundamental misunderstanding of which animals we need to be looking to in order to extrapolate to humans and how the stressors involved in research differ (or are similar to) extinction sleep training. As always I state my case: In the absence of any evidence supporting extinction sleep training as beneficial (or even benign when you actually look at the research as we just don’t have it), a lot of anecdotes of problems (especially with certain temperaments and populations and which matters when we lack research), circumstantial evidence of risk of harm (such as the effect on the period of hyporesponsivity and the vagus nerve), questions on the efficiency and duration needed to obtain “results”, and the fact that there are many gentler alternatives to guiding our children’s sleep, why risk it?

____________________________

[1] Sapolsky RM. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company LLC, 1994. [2] Kok G, van Rijsbergan G, Burger H, Elgersma H, Riper H, et al. The scars of childhood adversity: Minor stress sensitivity and depressive symptoms in remitted recurrently depressed adult patients. PLoS One 2014; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111711 [3] Monroe SM, Harkness KL. Life stress, the “kindling” hypothesis and the recurrence of depression: Considerations from a life-stress perspective. Psychological Review 2005; 112: 417-45. [4] Hyland ME, Alkhalaf AM, Whalley B. Normative minor childhood stress and risk of later adult psychopathology in Saudi Arabia. International Neuropsychiatric Disease Journal 2014; 2: 94-103. [5] Gunnar MR, Donzella B. Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2002; 27: 199-220. [6] Loutzenhiser L, Hoffman J, Beatch J. Parental perceptions of the effectiveness of graduated extinction in reducing infant night-wakings. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 2014; http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2014.910864. [7] Lyons DM, Parker KJ, Schatsberg AF. Animal models of early life stress: implications for understanding resilience. Developmental Psychobiology 2010; 52: 402-10. [8] Sussman RW. Primate ecology and social structure. Volume 2, New World Monkeys. Needham Heights (PA): Pearson Custom, 2000. [9] http://www.centerforgreatapes.org/treatment-apes/about-apes/ [10] Ellis J, Dowrick C, Lloyd-Williams M. The long-term impact of early parental death: lessons from a narrative study. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2013; 106: 57-67. [11] Gertler P, Martinez S, Levine D, Bertozzi S. Losing the presence and presents of parents: How parental death affects children. Berkeley, CA: Haas School of Business. 2003 Oct. [12] Price AMH, Wake M, Ukoumunne OC, Hiscock H. Five-year follow-up of harms and benefits of behavioral infant sleep intervention: randomized trial. Pediatrics 2012; doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3467.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

[…] (and it does work), it’s not necessarily harmless. Evolutionary Parenting looks at the science behind exposing our kids to stress, and what’s actually going on neurochemically in their brains when this happens. […]