By Justin Coulson

When people talk about ‘disciplining a child’, they usually mean ‘punishing’ a child. The punishment is supposed to help children learn, but research tells us punishment is an ineffective teacher.

When people talk about ‘disciplining a child’, they usually mean ‘punishing’ a child. The punishment is supposed to help children learn, but research tells us punishment is an ineffective teacher.

Good discipline (that actually works!) is really about teaching our children how to act in good ways. It’s about socialising them, and helping them to recognise and understand what behaviours are acceptable and what behaviours are not.

How do we typically ‘discipline’?

Ironically, if I were to ask you what parents’ most common disciplinary strategies are I’d imagine you might offer me a list like this:

i. Yelling

ii. Threats

iii. Smacking

iv. Time out (this is generally the preferred ‘discipline’ method)

v. Removal of privileges – especially technology

vi. Grounding (for older kids)

vii. Bribes and promises

viii. Praise

I find this list fascinating for one primary reason: The list displays an absolute reliance on parental power to (as Alfie Kohn suggests) do things to our children.

Do these strategies “work”?

Well, that depends on what you mean by do they work. If you mean, do they shut down the unacceptable behaviour, then research says “yes”. But if you mean teach kids good way to act, and help them internalise that, the answer is a clear and resounding “no”.

So, if these strategies don’t do anything except provide immediate relief, why do we use them? I suspect that we use these strategies because:

- They require no thinking

- They require no skill

- They require no perspective

- They require no compassion

In short, they require no effort.

All that those strategies require is someone with power (you) and someone without it (your child). So long as you’re bigger you’ve got it made.

I guess what this means is that these strategies do actually work…

But work to do what?

Is there any effective teaching occurring?

I know this is confronting – perhaps even provocative. I’m being quite deliberate about it. But research shows quite clearly that the more punitive the ‘discipline’, the less real teaching occurs.

Here are five research findings that point out why these low effort, low skill strategies won’t help you with disciplining your children – that is, teaching them good ways to act.

- 1. It’s lousy for your relationship.

If someone you loved was regularly yelling at you, threatening you, isolating you, or hurting you, it is unlikely that your relationship would be a positive one. Think about it. If your boss or spouse was constantly yelling, blaming, or even hurting you, you’d more than likely leave the relationship as soon as possible. Of course you’d forgive the occasional brain-snap, but if it was the consistent pattern of behaviour in the relationship, chances are you’d question whether the relationship was healthy, and you might even end it.

- 2. It creates resentment, fear, sadness, and anger

Research tells us that using our power to get what we want leaves others (including our children) with feelings of resentment, fear, and sadness towards us, often culminating in angry outbursts – even when the force is the ‘sugar-coated’ kind where we use bribes and rewards. When we take away people’s autonomy, they feel unhappy toward us.

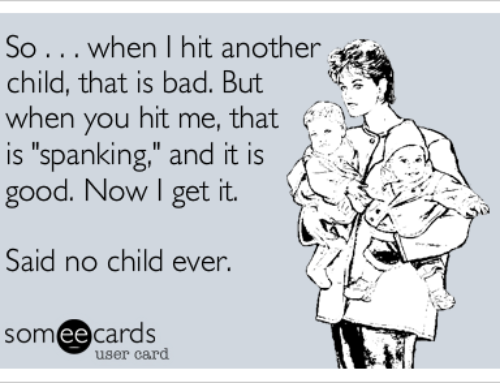

- 3. It teaches kids that power is how we get what we want

Experiments have shown that kids who have parents that use power to get what they want are more likely to treat their peers the same way. They’re more likely to bully in the playground. They’re more likely to use threats in relationships, like “I won’t be your friend if you don’t give me a turn.” Our example teaches kids lessons, but it’s often not the lesson we had hoped they’d learn.

- 4. Ultimately it stops working

One evening after an extended family dinner my 2 year-old niece refused to take a bath. Her mum threatened her:

“Paris, if you don’t get in the bath right now I’ll come over there and smack your bum!”

Paris turned around and stared at her mum. Then she stuck her backside in the air, spanked herself a few times and shouted, “Fine. Smack my bum!”

Eventually our threats stop working. Our punishments fail. Our yelling falls on deaf ears. And then there’s only one way to go – harder. Similarly, after a while, our bribes need to get bigger to entice the kids to do was we ask. What was once exciting is now not nearly enough.

This is, at least in part, because when we use power and control techniques to motivate, motivation becomes extrinsic. That is, children do what we want out of fear or on the promise of reward. They’re not doing it for internal reasons. They’re not doing it because they want to do the right thing, or because it feels good to be kind rather than cruel. It’s all about them, and all about avoiding trouble or getting the goody.

- 5. It stops kids learning

Threat of punishment can send kids’ emotions through the roof. When children’s emotions are high they don’t take much in. They’re too busy focusing on self-preservation. So they can’t learn what we want them to.

This means that punishments and rewards get our kids focused on themselves – and they don’t develop empathy. Without empathy, children don’t learn why we don’t hit, or why we treat others kindly, or why we speak politely, or why we say sorry. They simply do as they’re told to avoid the punishment. Rather than turning our children’s perspective towards others, punishment and rewards draw children inwards. It is all about what is in it for them, or how they can avoid being in trouble.

In a nutshell

Setting limits is about instilling discipline in our children. And discipline is not necessarily about ‘consequences’. Rather, discipline is about teaching good ways to act.

Our standard methods of discipline are generally more focused on consequences and punishment than teaching, and as such, they generally fail. While we hope that consequences will teach, research and experience suggest they will not. There are better alternatives. But they can often require more of us, and may mean we have to work slower (at the start) to help teach our children well.

My ebook, Time Out is Not Your Only Option: Discipline strategies for every child (that parents can feel good about), describes eight ways to build discipline in your children while building your relationship with them at the same time.

[…] rights too, Why I do not use time out or time in; Bullying my kids), Evolutionary Parenting (e.g. What is discipline), PhD in Parenting (e.g. 3 R’s of toddler discipline: repetition, reaction, reassurance), Lori […]

Thank you so much! It is a huge let peeve of mine when people say discipline when they really mean punishment. To discipline means to tab, as you pointed out. I’m always thrilled when I find like minded people!

Am interested in the ebook but the link won’t work! Is there a different link I may access the book from?

It’s important to emphasize that discipline is NOT punishment. Punishment is different than discipline in the fact that while discipline teaches a lesson, punishment focuses on payment for the ‘crime’. For example: Punishing a child for not picking up their toys might involve spanking or time out from playing with said toys. Discipline, on the other hand, would be taking the toys away from them for two or three days; leaving them with little to play with.