The following videos and text are different, but complimentary. That is, the text that follows is NOT a copy of the text in the videos.

Recently, I received a question from a parent to the tune of, “What are the alternatives to a tantrum that you teach your child?” It was a great question as I have spoken at length about the need to help our children find alternatives, yet had offered no alternatives (see this piece here). In fairness, part of the reason I offer no concrete solutions (which you won’t see here either) is that each child and each situation is different thus parents will need to try various things to see what work s for them. However, there are certain steps that parents should know about in order to help them find out what does work. As I only have my own experiences and mind to draw on, I don’t imagine what I include here is anywhere near comprehensive but I share these steps and some ideas in hopes that they may either work for you or help you brainstorm some of your own ideas. As always, if you have ideas you’d like to share, please comment at the bottom so all parents can benefit.

s for them. However, there are certain steps that parents should know about in order to help them find out what does work. As I only have my own experiences and mind to draw on, I don’t imagine what I include here is anywhere near comprehensive but I share these steps and some ideas in hopes that they may either work for you or help you brainstorm some of your own ideas. As always, if you have ideas you’d like to share, please comment at the bottom so all parents can benefit.

Step 1: Recognizing Frustration

As mentioned in the original piece, although the triggers for tantrums will vary widely, the causes may be very simple – hunger and tiredness being the biggest two. When our children are hungry and tired, it is up to us to help that situation by feeding them or letting them rest. Remember that as this alone can help curb several tantrums.

However, another factor also comes into play and this one increases with age: Frustration. Tantrums can occur as children try and fail at new tasks or struggle to express themselves to others or in the midst of play when things don’t go as they’d like (along with many more reasons). When hunger and tiredness are also at play, you’ll often see frustration go from 0 to 100 in about 30 seconds and this is your cue to remove the child from the situation and get them fed or rested. When hunger and tiredness aren’t at play, you will often see frustrations gradually build up (if you’re paying attention and let’s face it, we can’t always be paying that much attention). This is where learning to recognize one’s own frustration comes into play.

When our children can learn to identify when they are starting to feel frustration levels rise, they can then learn to take advantage of the other alternatives we’ll get to below, but this requires understanding of one’s own emotions. As you won’t know what frustration feels like for your child (just as it likely feels physiologically different for you and everyone else), the ability to help your child will be based on lots of experiences in which you are with them when they start to experience this.

What do I mean? If you take regular times to engage in tasks that are slightly above your child’s level, you will likely have ample opportunities to be with them as they experience frustrations. This is your chance to learn your child’s cues for frustration and then talk to them about their emotions at these stages (make sure to help label the emotion too). When you see your child show the first sign of frustration, ask them how they feel and get them to become aware of the sensations associated with this build-up to a meltdown. This is also your opportunity to model your own awareness of frustration. If you engage in the task and “feel” frustrated (in quotations as you may be acting a bit here, but modeling in the moment too can be very helpful), you can talk about how you feel in the moment and identify these feelings as frustration.

These discussions serve to give your child the awareness of their various emotional states and the vocabulary they need to discuss their emotions, a critical part in the development of self-regulation. There is quite a bit of research that links parental discussions of emotions to greater emotion regulation

Step 2: Calming Down

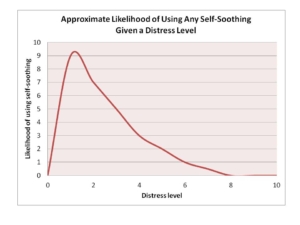

The calming down process is really the means by which we try and avoid the tantrums altogether. Learning this process also serve to help the child better navigate social situations to help them better achieve their various goals. The most popular adage when it comes to children and tantrums is to try and get your child to “use their words”. I have been guilty of these (even recently) as it sounds so nice, but it actually ignores some rather important information: If your child isn’t using his/her words it’s because s/he either doesn’t have the vocabulary to express it or is in such a heightened emotional state that access to these words and thoughts is being blocked. That is, our ability to regulate ourselves is highly dependent upon the degree of distress we’re experiencing and if it’s too high, we are unable to calm ourselves (see here for a summary).

Thus, the focus in this section is not to ask your child to do something that is physiologically impossible, but to combine the knowledge of building frustration with certain techniques that can help them alleviate this frustration, making it easier to do things like discuss what’s wrong or solve the problem for themselves (which we’ll get to next). And because it’s worth repeating, this is why when things like hunger or tiredness are in the mix, nearly nothing will work except addressing these physiological problems so I always recommend you be cognizant of these when out and about too.

Walking Away (for a Moment)

One of the best things I find for most people is to simply walk away for a minute. Changing the environment (i.e., removing the cues to frustration) and a bit of movement can help immensely. Our brains can become so focused on one thing that breaking away is what our brain needs to “reset” itself and focus on physiological regulation instead of the frustration at hand. Children may be particularly resistant to this at first if they fear they are being told to stop what they are doing or that they will lose the toy/game in question. This is where modeling is essential as they can see you get up for a moment and regroup (talking your way through it the whole time so your child gets the benefit of understanding exactly what you’re doing) and then return to play again. At the start, when you ask your child how s/he is feeling, if some of the feelings of frustration are being mentioned, you can ask your child if s/he wants to take a moment and you’ll “guard” the game/toys/whatever for him/her. This moment alone should not be forced as it needs to be something your child learns to identify and do for him/herself.

Deep Breathing

Some people are able to simply stop what they are doing and take a few deep breaths. For children, the presence of the stimuli in front of them may make this a less effective alternative and you may need to model closing your eyes if you’re going to do this one with your child. However, deep breathing for a minute is immensely calming and can help your child (and you) regulate in the moment. One thing to remember is that although the first few breaths may be enough to start the calming down process, really this needs to be a 1-2 minute (if not more) exercise.

Singing or Being Silly

In many cases, children will quickly be able to calm down when able to act silly or sing a song. If this becomes a routine in your house that everyone takes part in, it becomes easier for your younger child to incorporate this into their own experiences. In our house, we use the silly faces when we’re getting angry. So the moment my daughter sees me getting angry about something (at anyone or over anything), she reminds me that I have to make a funny face which works to alleviate my own anger and makes her laugh. In turn, she’ll sometimes remember to do the same on her own, but regardless is good about it when I remind her to make a funny face. Singing also helps as it forces kids to take deep breaths. Not only does it force deep breathing, but a good song – perhaps a silly one? – can help kids feel better as well.

Step 3: Solving the Problem

The goal of (most of) our parenting is to help our kids learn to solve their own problems. This takes time and takes discussion and modeling from us. Once your child has learned how to identify frustration (and anger) and calm themselves to a point where they can act to solve problems, we need to help them learn how.

The first thing is simply to ask your child to come up with ideas him/herself. Your child is likely more capable than you think of solving their problem and if given the time and support, will do it on their own. This is particularly true for non-social frustrations where there are multiple practical ways to solve problems (whether it’s building something or trying to get a particular snack). If your child’s idea doesn’t work, you may want to offer up a partial solution to see if your child can figure out the rest. The idea of having your child feel responsible for the solution is critical as it builds their confidence in their own abilities to solve their problems.

However, sometimes there is another person involved and some mediation is necessary. In these cases, focusing on expressing what’s wrong (depending on the child’s age, you may need to help) and having both people try to come to a solution that both can live with is key. This is often where you see people say “Use your words” and it’s true if the child has them, so make sure you’re always talking about emotions and situations to help your child build this type of vocabulary. Again, try to let them work it out themselves, with you there to mediate, not dictate.

Some people may be feeling frustration over the fact that there are no concrete things to do listed here in this section, however, that is for two main reasons. First, there are so many reasons why children may be upset that trying to come up with generic solutions simply won’t work. Second, each child is different and a solution that works for one won’t work for another, even given the same situation. Thus, the onus is on you, the parent or caregiver, to know the child and what they are capable of and what will help them in a given situation.

One final reminder: This process of helping our children takes time. Lots of it. You can’t expect to have a child who suddenly no longer reaches a tantrum state after one or two discussions. Furthermore, some kids will learn to identify emotions faster than others and some will implement the calming down techniques with ease earlier than others too, but some won’t. Some will take a lot of practice and a lot of time. This doesn’t mean you’re a failure as a parent. In fact, often some of the most high-needs kids are the ones that require more time because they struggle with physiological regulation. There’s nothing “wrong” with them or you, just that their physiological development is different from others in that they are more likely to hit high distress more easily and faster than other kids. Learning to calm down is thus harder because the sweet spot for getting calm is a much shorter period for these children. Remember that you’re working with your child, not against them, and not with another person’s child, so there’s no need to hold your child to any other timeline than the one they’re on.

For more information on discipline, I suggest:

[amazon_image id=”0345548043″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]No-Drama Discipline: The Whole-Brain Way to Calm the Chaos and Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind[/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”0399160280″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Peaceful Parent, Happy Kids: How to Stop Yelling and Start Connecting[/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”0345442865″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Playful Parenting[/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”0988995832″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Gentle Parent: Positive, Practical, Effective Discipline (A Little Hearts Handbook)[/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”0988995840″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Jesus, the Gentle Parent: Gentle Christian Parenting (Little Hearts Handbooks)[/amazon_image]_______________________________

[1] Brophy-Herb HE, Stansbury K, Bocknek E, Horodynski MA. Modeling maternal emotion-related socialization behaviors in a low-income sample: relation with toddlers’ self-regulation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 2012; 27: 352-64. [2] Brownell CA, Svetlova M, Anderson R, Nichols SR, Drummond J. Socialization of early prosocial behavior: Parents’ talk about emotions is associated with sharing and helping in toddlers. Infancy 2013; 18: 91-119.

[…] Een heel snel en kort rondje leesvoer deze zondag Helping Kids Find Alternatives to “the Tantrum” | Evolutionary Parenting | Where History And Sci…. […]

Great piece! I have since used singing a song as a diversion when I see frustration mounting! Breastfeeding is also a great calming tool.

I really appreciated the book Toddler Calm, which you reviewed on your website, for it’s tools- particularly avoidance of stressful situations!

[…] Helping Kids Find Alternatives to “the Tantrum” | Evolutionary Parenting | Where History And Sci…. […]

How should I transition to more of a gentle parenting approach with my 6 year old? In the past we have used alot of time outs but reading some of your other material I think it may be more of a compliance than her learning or coping better, especially given that at times she reverts for small periods back to the negative behaviors (lying, is a HUGE one). Also I have noticed she bottles up her feelings and then melts down (I try to be understanding because its not often) I would really like to facilitate better communication between us and better coping for her. I have a 7 month old that I wrote you about previously and I intend to take more of the gentle approach with him but with her I don’t know where to start. Shes a great kid and we have a good relationship for the most part but I really feel lost as how I can get her to be more open about her feelings, and eliminate the lying. The biggest issue with the lying is I feel there is a reason for it (its excessive and about even small things like making up stories about school or conversations with people) but I cant decode it. Its very frustrating for me because I was a fairly honest kid (even when my mom didn’t want me to be) so I dont understand where the behavior stems from.

Although we do not want to encourage aggression in children sometimes having an outlet to their frustration is helpful especially in boys who tend to be more physical. As an ex- nursery head teacher I didn’t always know what triggers were common for every child. However we did have some strategies for dealing with the aggression. One way was to have a session with play dough where they can pummel, squeeze and hit the dough and have control over something. For another child who was angry with his parents who were splitting up and would hit anyone who came within reach we made a punch pillow tied to a down pipe in the corner of the room. He was encouraged to go and hit the pillow rather than others and soon recognised his feelings and before he hurt anyone he would go over and use the pillow and come away saying ‘ok I feel better now and then we could talk about his feelings. I noticed that other children also would use it. A third strategy was a music session where they could bang, shake and stamp their feet especially in time to a rousing march tune. Hope this will help some parents who struggle with ‘angry’ children.

I enjoyed the article- but the picture used at the start is extremely triggering and completely unrelated to the content. Please consider replacing it.

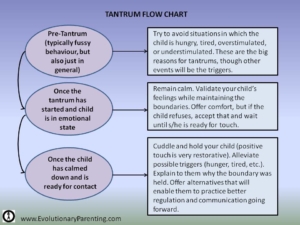

What picture? The only pictures that pop up for me are the tantrum flow chart and the distress by self-soothing chart… so I’m confused.

This is a great insight. Every kid has his moments.

[…] Een heel snel en kort rondje leesvoer deze zondag Helping Kids Find Alternatives to “the Tantrum” | Evolutionary Parenting | Where History And Sci…. […]