This other weekend my daughter learned to ride a two-wheeler bike (no training wheels). My husband and I weren’t too sure what to expect as she had been using the push bike and had decent balance, but she just turned five and we remember being older. However, by and large, the experience was great. She had it down in thirty minutes so long as my husband started her off. What was apparent in these minutes, though, was that it also provided an excellent example of when our children’s anger isn’t really anger at all and why we need to respond with patience and understanding instead of threats and punishment.

You see, there would be times when my daughter might think she was ready and start to move, so my husband would start to push her (between my back problems from the car accident and pregnancy, I was no good in this department) and there’d be an almost-fall and she’d get angry and start yelling at him. Was this appropriate? No. What is because she’s a little brat? Not at all.

I’m sure every parent of a child over a year (and some under) has experienced this moment where you do something seemingly benign, there’s a mini-moment where something may go wrong that is sensed by all (including the child), and the child ends by getting really angry and taking it out on you. We as parents tend to get a little flabbergasted by this and almost inevitably find ourselves defensive and angry in turn.

What’s going on?

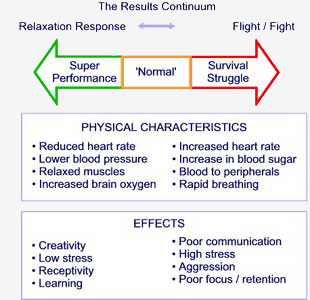

Although there are going to be times your child is truly pissed off at you, these times are different. These times are great examples of how our bodies respond to stress and fear. Our children aren’t angry in that they have righteous anger about something we’ve done, they are in the fight or flight response (which really isn’t totally accurate but is accurate enough to serve the purpose for this discussion) because they’ve been stressed or scared.

In the case of my daughter, she was learning something new, she knew she might fall and these moments inevitably came after she sensed she might fall. She was caught (or caught herself) each time, but that fear and the associated rise in the sympathetic nervous system was enough to send her into battle-mode, especially as flight wasn’t really an option in that case. Getting angry back at her would have served zero purpose and potentially been harmful.

Why would it serve no purpose? Primarily because she’s responding in a nearly automatic way to what’s happening. Getting angry won’t change her feelings of stress or fear and how her body is then revving up for an acute stressor. Getting angry will simply put a wedge between her and us that will be difficult to bring down. Getting angry enough means she may stop lashing out, but she’ll still feel that stress internally.

This is where the potential harm comes into play. When humans have a stress response to an event, our body – thanks to its years of evolution – is thinking it’s facing an acute physical stressor and floods the body with the various hormones needed to handle this particular type of stress. Some systems are shut off (like the storage of energy from food) and some get turned on (like the adrenal system which gives us that energy to try and outrun a lion). With the adrenaline coursing through our bodies, we need an outlet for it or we face physiological harm.

Now, physiological harm will not come after one event in which we can’t physically or emotionally express what is happening in our bodies, but if the lesson we teach our children is not to express themselves when they feel this stress, this becomes a repeated thing, for stress they will face throughout their lives. This is unhealthy in that the excess adrenaline that comes from not expressing emotions (have you ever noticed that when angry you also physically react?) stays in our body longer and can harm various parts of our body, most notably the cardiovascular system. (It’s also incredibly unhealthy to have to face it too frequently even if you do respond because of the wear and tear on your body, which is why firefighters tend to have a shorter-than-average lifespan, even factoring in on-the-job hazards.)

What do you do? I have personally found that understanding the process myself helps me keep my cool. I don’t often get stressed or defensive or angry and that allows me to respond to my daughter in a way that doesn’t exacerbate the situation. It also helps me teach her about how our bodies process these situations and why we feel the way we do.

“It’s really scary when we think we’re about to fall, isn’t it?”

This one sentence helped several times with my own daughter in that it allowed her to shift her emotions from the anger to the fear and upset that came with that. There were tears on my shoulder and then a regrouping before trying again. If you think about it, when our children are clearly scared and have an outlet for that fear, we can offer comfort to them in hopes of making them feel safe. When they don’t understand where the fear is coming from, they experience the flood of adrenaline, the fight or flight response, and seek to lash out at the closest person. Bewildered, most parents experience their own stress response and lash out right back at their child.

When we understand what’s happening, though, we respond differently. We don’t see an angry, defiant child for no reason. We see a child who’s been scared and doesn’t know how to cope with the surge of emotions and adrenaline in her body. As such, we can respond with the same comfort and empathy we would if the child were scared of a clown (they are freaky as anything, don’t try to tell me otherwise) or the dark. We can discuss their emotions, the situation, and try to help them find ways to express these emotions more appropriately moving forward. For us, these discussions didn’t mean my daughter could suddenly change. Every time she continued to experience that anger, but we also continue to talk about it. She’s starting to understand that her body may react in a way that she doesn’t intend and that’s okay. The more she learns about this process, the more control she gains over it.

It’s worth noting here that us adults are not immune to this at all and can take a page out of being more mindful of our situations and emotional reactions. How many times has your child done something where they might have been hurt, but ended up okay only to have us yell at them for the experience? If we were to catch our kids doing something very dangerous before they were at risk, we’d likely calmly tell them to stop and explain why. After, however, we’ve experienced the intense fear and surge of adrenaline. So we lash out. We’re not actually angry at our kids, we’re terrified we may lose them and that fear, physiologically speaking, makes us fight what scares us: our kids. Being aware of how this automatic physiological response makes us behave gives us the opportunity to build up our toolbox for how we cope. It may be ensuring we have a few minutes before talking to our kids to allow us to express our own anxiety and fear. It may be using up that energy by doing 10 squats. Whatever floats your boat, so to speak.

Next time your child lashes out seemingly without reason, don’t assume your child is being rude or irrational, but look at what happened prior to see if you can identify the real cause and help your child through that. Oh – and do the same for yourself as well. You deserve the empathy too.

For an incredible read on the science behind the stress response system, I *strongly* recommend you read the following:

Leave A Comment